Trans: When Adolescent Survival Strategy Becomes Family Breakdown

How Miscommunication and Parental Panic Push Kids Toward Transition. Gender Identity Ideation Series Part TWO.

Note: The "play” button at the top is not a decoration. It is an audio-taped version of myself reading this essay. Also note, there are videos in the first section of this essay, so if you are a listener, keep this in mind.

This piece will be available in full for paid subscribers.

How Family Dynamics Shape the Path to Transition

We know that the transgender framework has become the most ubiquitous sense-making model for Gen Z, especially during adolescence. It offers broad statements about bodily discomfort that make a child feel as if their body itself is wrong, just because the child feels as if it is—laying the groundwork for an identity that doesn’t just interpret distress but redefines the self entirely. Once a child begins to believe that their body is not just uncomfortable but wrong, the idea of transition presents itself as not only a logical conclusion but as the only solution.

In the previous essay, I discussed how ideation begins after a young person’s confusion about emotions they cannot explain with their own words becomes rationalized as signs that they are transgender—a process that, when coupled with a framework offering a way out, becomes increasingly difficult to divest oneself from. I described how ideation begins: with a set of confusing thoughts or sensations, and with the desperate desire to make sense of them using any and all available tools. I also described how gender identity ideation—the process of thinking about oneself as the opposite sex, planning a social and/or medical transition—is what truly propels a young person along the transition pathway. I alluded to the fact that these identities don’t remain static; they grow with a child, becoming more entrenched over time.

Read my essay titled “Trans: When Coping Mechanism Becomes Identity” before continuing if you haven’t already.

Trans: When Coping Mechanism Becomes Identity

(Note: The play button at the top of this post is NOT a decoration. I have painstakingly audiotaped myself reading my essay, with a special little ad-lib at the end for my listeners. Please click on that play button if you would prefer to hear me reading this essay which I have written. Without further ado— I hope you enjoy the paper. Please comment you…

In this essay, I will expand on what I mean when I say that a teenager’s trans identity takes on a life of its own the longer it lasts, making it significantly harder to disembark from, by focussing on family dynamics. I will turn to my own story. I’ll describe how my parents’ handling of my gender identity crisis, despite their best intentions, only caused me to become further dug in. Their response, rather than helping me step back and reflect, ended up protracting the duration of my trans identity and made it difficult for me to disembark without the involvement of even more radical parenting moves and the added, exceptionally traumatic circumstances of contending with death while living in a Middle Eastern war zone.

Since we know that transgender identification latches onto the archetypal adolescent drive for individuation from one’s parents, we must not forget that parents remain the most powerful force shaping a child's trajectory—including how gender identity issues unfold. Dysfunction within the family dynamic can escalate conflicts and, over time, lead to alienation. We cannot simply dismiss these factors as the fault of the ideology (or the "glitter family") that a given child has latched onto for specific reasons.

There’s a reason your child found this identity—and a reason it is now tearing your family apart. Only a fraction of those reasons are explained by the existence and popularity of factually false beliefs around sex and gender.

From personal experience, I can say definitively: both deep dysfunction and simple but fundamental misunderstandings between parent and child often drive a young person to rebel against their body rather than against any other cause. If you want to help your child, you must stop blaming every outside force and start asking what parts of your family dynamic—whether through affirmation, non-affirmation, or sheer misattunement—have made this identity feel necessary for your child to protect at all costs. Until you confront that, your child will likely remain trapped on a path that leads only to deeper harm.

Family Dynamics Are Set Early

Since before I was born, my parents were committed to giving their child the best possible chance at life, by playing Mozart while I was still in the womb and pre-purchasing all of the parenting books about how to make their unborn child a genius. Everything was going according to plan until my mom’s pregnancy with me almost killed her. I was delivered emergently at 31 weeks, weighing about one kilogram.

Knowing my mom, I suspect that even as the doctors brought her back from the doorstep of death, she was already fretting at the news that my premature birth could spell a disaster for the rest of my life, through disabilities and developmental delays.

The NICU nurses reassured my parents that I would survive, largely because I refused to stay still long enough to die. The feeding tubes bothered me so much that I would toss, turn, and rip them out—fighting the machine before I even reached my due date. The nurses had never seen anything like it, and one of them joked, “Watch out, she’s gonna give you a run for your money.” That nurse, as it turns out, was some kind of psychic.

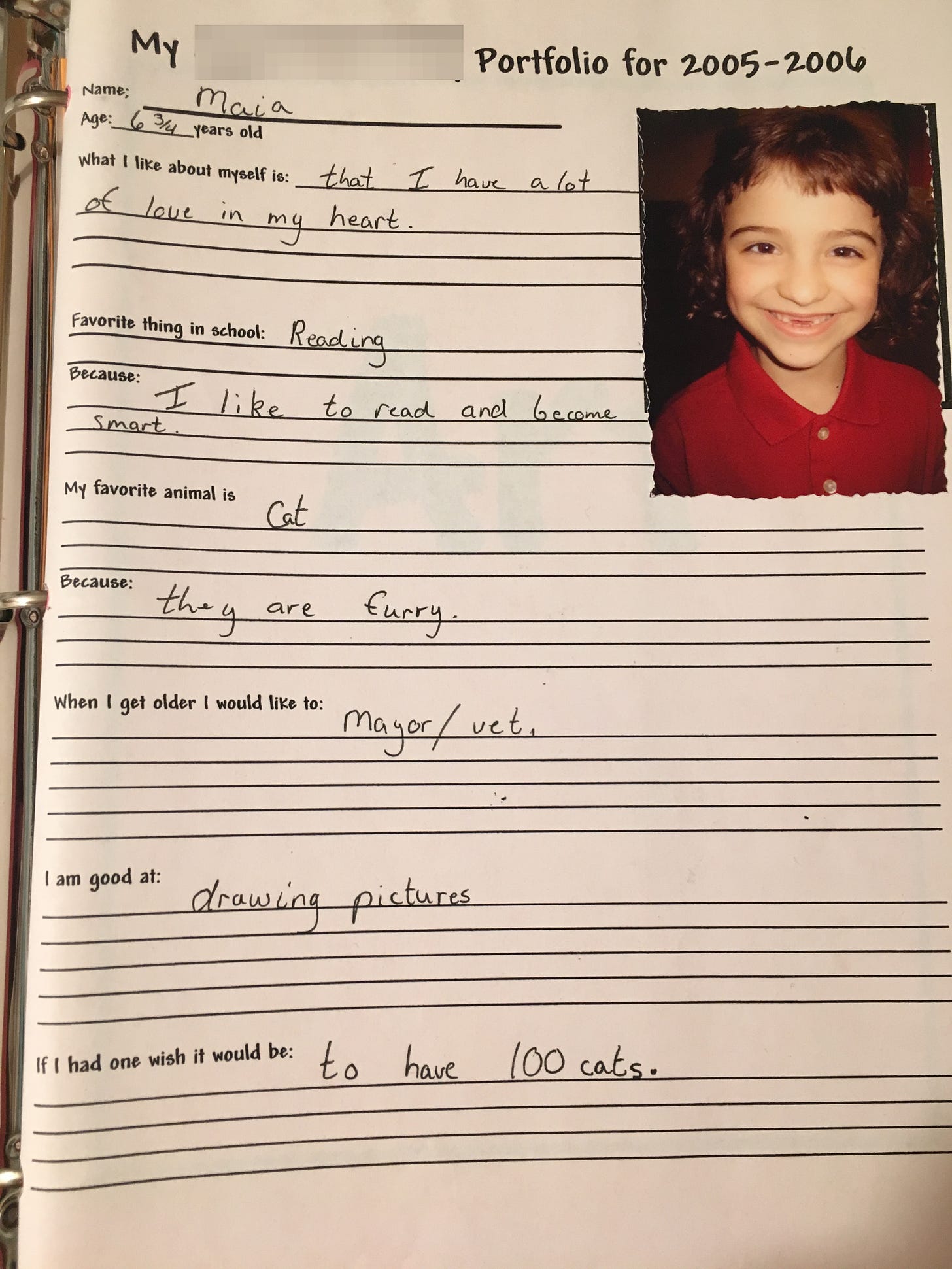

Everything about my life threw my parents for a loop. My early years were especially intense. My parents invested an insane amount of resources into me. I was followed closely by doctors for signs of delays, while my parents worked tirelessly to create the most enriching environment possible: I was read to constantly, surrounded by music in multiple languages, and raised bilingually. At my mom’s orders, my dad enlisted my grandfather’s help to build me some kind of crawling track—flying him in from across the world to do it—and yet, I never crawled. When I finally did walk, I walked on my toes.

I was a very atypical child in just about every way imaginable. I had significant developmental delays and spent my childhood being shuttled between an endless carousel of doctors, therapists, and specialists—each trying to correct the effects of my premature birth (leg braces, speech therapy, vision therapy and more) while also simultaneously aiming to turn me into a little genius. My mom recalls reading in a book that the very parenting strategies which make a child highly intelligent, also are useful in helping children who were brain damaged to recover

I had very clear gifts: I memorized entire children's books word-for-word by age two and used them to communicate complex sentiments with adults, sentiments which I did not posess the language or self-awareness to generate on my own—a behavior I describe as "copy-pasting," though others might pathologize it as "echolalia." I was bilingual.

(In this video, I recite from memory The Three Little Pigs— or whatever that book is called)

My verbal development was unusually strong, even though bilingual kids typically show an initial lag. I was sight-reading English words and translating them into Russian before I was even potty trained.

(In this video I am repeating over and over again, “the kitty is sitting and eating” in Russian. You will notice the toe walking)

But I also had quirks that alarmed the adults around me. My particularly humorless preschool teacher, obsessed with us putting our backpacks in cubbies and our coats on hangers, suggested to my parents that something was "very wrong" with me—because as a three-year-old, I would ask her every single day, with an exaggerated questioning gesture, where the cubbies were. My parents thought it was funny and whimsical. The teacher did not. Personally, I think the real problem was that she hated children. She was a real witch.

I was a quirky kid, but I also had real problems. I was obsessed with rare brain tumors. I had no interest in movies (I viewed going to the cinema as punishment) and instead preferred to read the parenting books I found lying around—because I realized at some point that I didn’t understand kids my own age. As a young child, it seemed like I had a wild imagination, which everyone praised, but the truth was darker:

I did not even remotely understand the difference between imagination and reality until puberty hit and I realized—horrifyingly—that I had a physical body. Until puberty hit around age 9.5, I thought it was very possible that I might magically turn into a boy. I also thought I might turn into an airplane. My grasp on reality was tenuous at best, even as my peers had for years figured out the difference between “real” and “fake.” Most kids understand the immutability of biological sex at a much younger age. That realization that I would stay a girl forever was jarring.

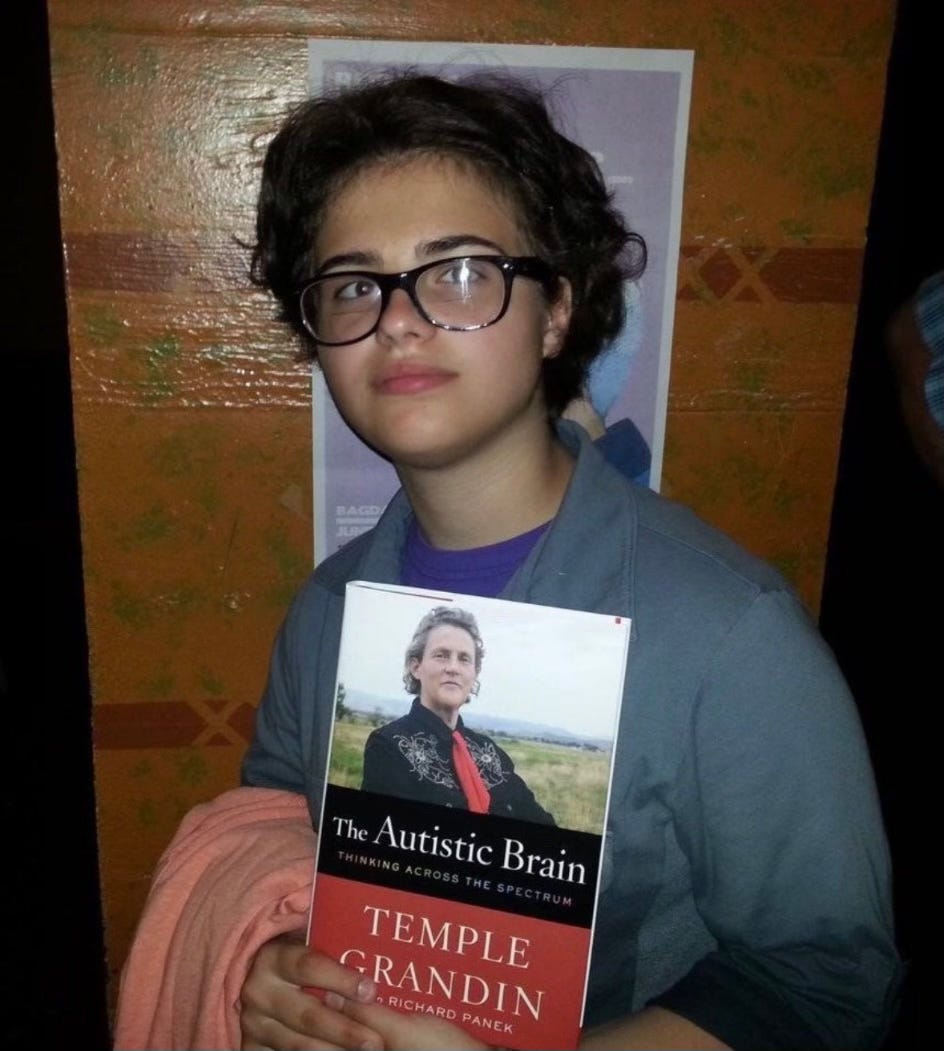

When I was 12, the same year I ‘came out’ as transgender, my parents realized that I was not picking up on social cues and that this was probably not something I would figure out on my own. I required a lot of correction from adults, interrupting me during my hours-long rants about the human brain, the human genome or my favorite niche neurological disease obsession of the week, reminding me to ask other people questions. Despite being oddly advanced in some ways, I didn’t learn to swallow liquids properly or to tie my shoes until I was 14—the year I was finally medicated for ADHD and realized that for my entire life, I had been living on a completely different planet from my peers.

Essentially, my childhood was defined by the collision between parents driven to create a successful, well-adjusted child and the reality of my complicated mix of gifts and developmental deficits. Their hypersensitivity to catching problems early saved me in many ways—but it also meant that harmless quirks and non-conformity, gender included, were flagged as issues needing intervention. The approach they took—to wage a war on my transgender identity, rather than trying to understand what I was trying to express through it—only raised the stakes for me, making it nearly impossible to disembark. It also caused us to become alienated for years. This essay will address why parental alienation occurs so often as a result of a child’s gender identity crisis.

We know that affirmation keeps kids entrenched in their trans identities, but we should not automatically assume that non-affirmation alone is enough to avoid that outcome.