The Misunderstood Autistic Girl to Trans Boy Pipeline

I Was the Girl With the Wrong Diagnosis, Not “Born in the Wrong Body.” Part 1

Note: The “play” button at the top is not a decoration. It is an audiotaped version of myself reading the essay. You can listen by clicking on it.

Note for LISTENERS: There are pictures and videos of me as a toddler in this essay, so if you’d like to see them and all of my other fun little images, make sure to scroll through the essay for them after listening.

Here’s your weekly reminder to stop sending my essays to your kids:

I'm a Detransitioner. Stop Sending My Essays to Your Trans-Identified Kid.

Note: the play button at the top is not a decoration, it is a recording of me reading my essay.

Without further ado—

Maia’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber by clicking on any of the buttons in the post.

Introduction: a “Quirky” Developmental Trajectory

From the outside, I was a talkative, precocious little girl—“hyper-verbal,” adults said, often with a note of admiration. I could recite books, mimic characters, and hold long conversations with grown-ups. But all of it was scripted. I knew how to perform language, not how to use it to connect. I didn’t understand how to play, how to read other kids’ emotions, or how to interpret the world beyond the narrow logic of my own sensory and cognitive experience. What looked like giftedness was, in reality, a mask for deep confusion. And like so many girls on the autism spectrum, I wore that mask so well that even the professionals missed what was underneath.

In this essay series, I will use myself as a case study for how autistic traits get missed in girls and explore how I think that increasing the accessibility of autism diagnoses for younger girls could be one protective mechanism against them self-diagnosing as transgender in adolescence.

I will use myself as a case study because I can speak from my own experiences of being constantly in and out of doctors’ offices throughout my childhood—how all those visits to specialists and therapists weren’t ever grouped together due to a misunderstanding of how autism manifests in girls. In this essay, I’ll focus on the first (mis?)diagnosis I received: OCD. My OCD diagnosis came far before my trans identity declaration and marked my first real encounter with psychiatry. That encounter subtly began to reshape my self-perception and paved the way for a deeper, ongoing search to explain why I felt so different from other kids—using a pathological lens. That first (mis)diagnosis led to a misattribution of my symptoms, and the root cause was never addressed.

This is the first part of a three part essay series about the ways I as a child was misunderstood—both by experts and institutions, and by many adults in my life who just didn’t know what to make of me. This essay is about how a child like me, desperate to understand herself, could end up attaching herself to the wrong frameworks just to make sense of the chaos in her mind. This essay series is the story of how I was missed—not because I was invisible to the medical establishment, but because I looked too competent to be questioned over the peculiar set of issues I had. At the same time, though I focus on myself as a case study in these essays, these essays aren’t just about me: they’re about the potentially hundreds of thousands of girls growing up in wealthy, Western countries with robust psychiatric systems, who aren’t getting the help they need for the problems they have— and so instead, find themselves staring down the barrel of lifelong transgender medicalization because of an identity crisis spurred on by growing up misunderstood by everyone, and because in some fundamental way, these girls also misunderstand themselves.

In my second essay in this installment about how autistic traits were missed in my case, I’ll explore what happened after I declared a trans identity, the psychiatric involvement that followed, the second (much more accurate) diagnosis I received of ADHD, and of how of course, despite my sustained obsession with autism itself— no autism diagnosis was ever considered.

In my third essay, I’ll look at how the nature of misdiagnosis—or total lack of proper assessment—of girls on the spectrum creates specific vulnerabilities that can contribute to the development of what we now call gender dysphoria, or a gender identity crisis, in adolescence.

I hope that by the end of this three part essay series, anyone who is entrusted with the care of a neurodivergent girl who has traits of autism or ADHD, be they parents, teachers or therapists, may be able to spot potential ‘signs’ of these traits so as to better understand the child in their lives in order to protect them from an ideology which preys upon such children being chronically misunderstood.

Why Autistic Girls Are So Often Misunderstood in Early Childhood: My Story as a Case Study.

I have always loved talking. My love of gab first made an appearance in my effortless childhood bilingualism, and then expanded to include two more languages. No matter how far I strayed from fluency in any language, I simply would never stop talking.

At two years old, I was already reciting entire children’s books from memory, and echoing lines from Soviet children’s TV shows and translating them into English to use in place of authentically constructed speech. In the beginning, I wasn’t expressing my original thoughts, but rather using scripts lifted for the purposes of recycling someone else’s often thoughtlessly discarded words, phrases or entire conversations. As I got older, I would discuss the ongoings of my life, including the experience of splitting open my forehead and then later, my eyebrow, by projecting these experiences onto my toy cats.

As a toddler, I was unusually altruistic and wouldn’t leave for the park without putting organic lollipops into little plastic baggies to give away to the other kids. But I didn’t really know how else to interact with them, besides giving them things. I suppose this could have been normal if I had outgrown this relational style and gone onto the phase of saying that things are ‘MINE’— but I just… didn’t. I spoke clearly and constantly, but not reciprocally, unless in some rare case another child said something interesting to me which I genuinely wanted to pick their brain about. Even the questions I asked others were directly scripted from adults both the words themselves, and the tone. By every measurable metric, I was verbally gifted and highly animated, so not much attention was paid to the nature of my unconventional conversational and relational strategies.

I had an impeccable ability to notice the pain of dogs twice my size at the dog park, including those who had limps only perceptible to their owners following their almost full recovery from an operation.

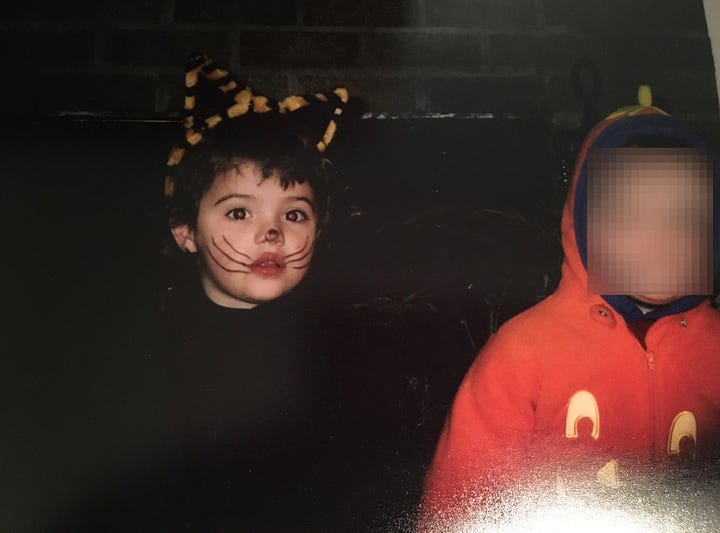

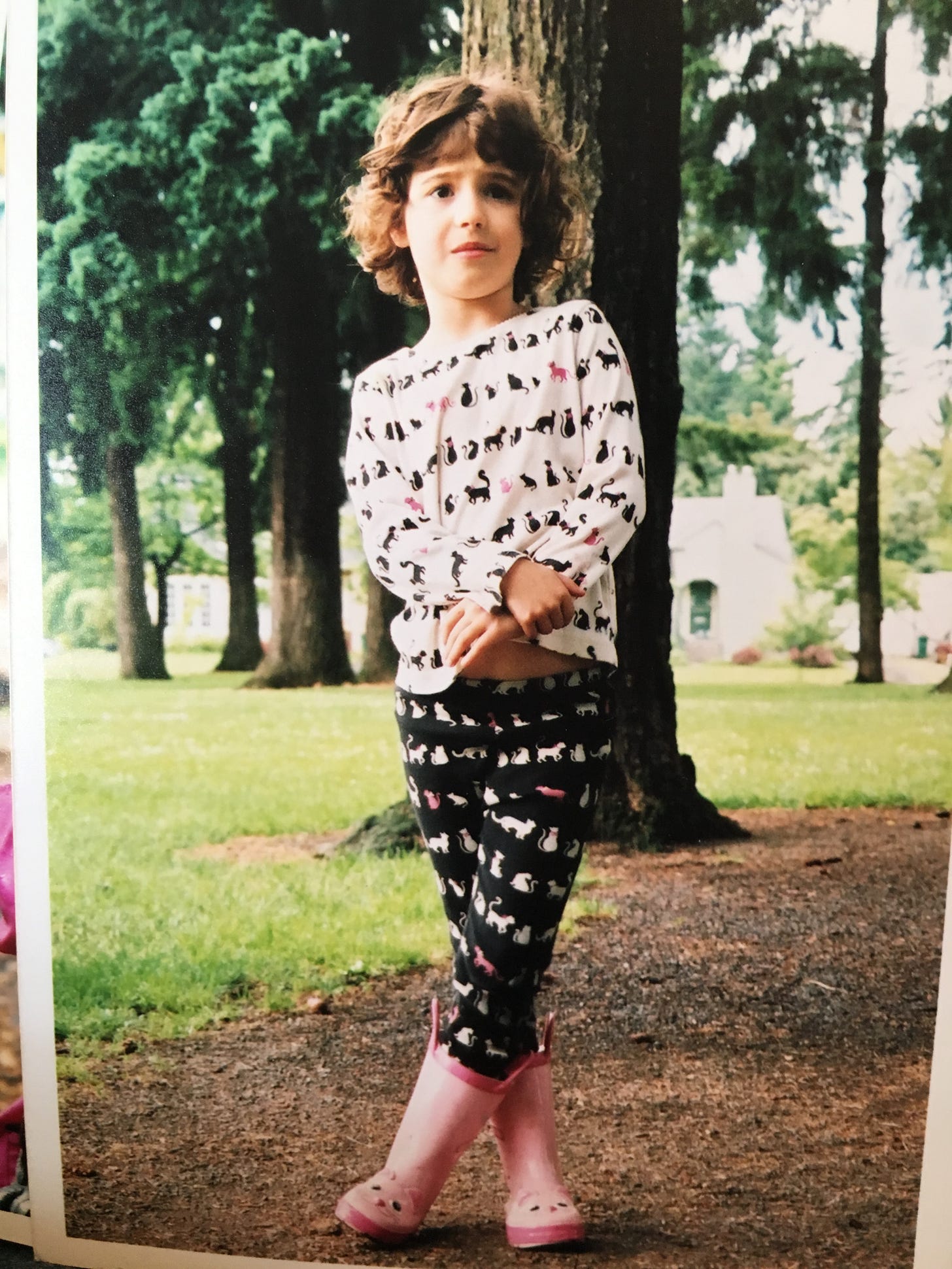

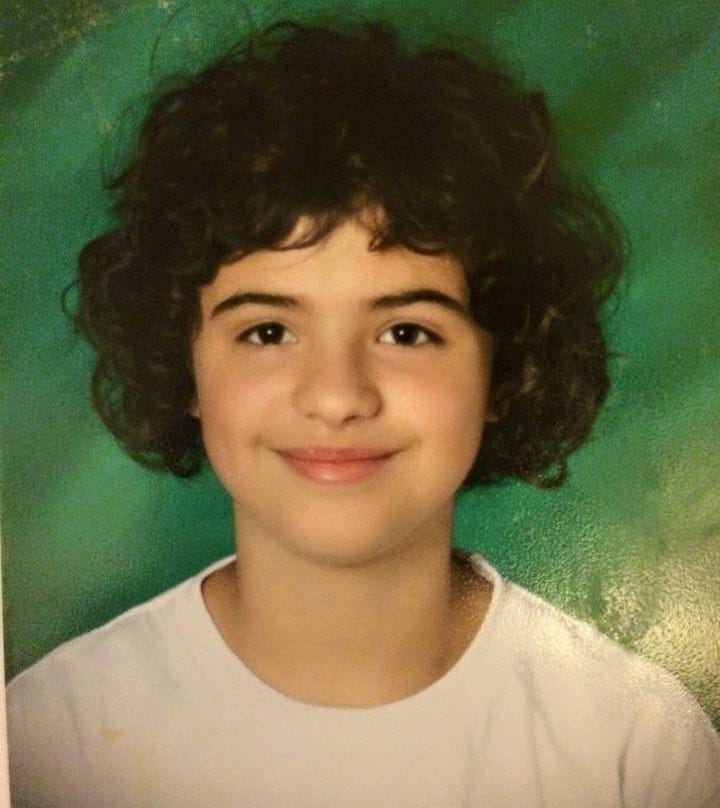

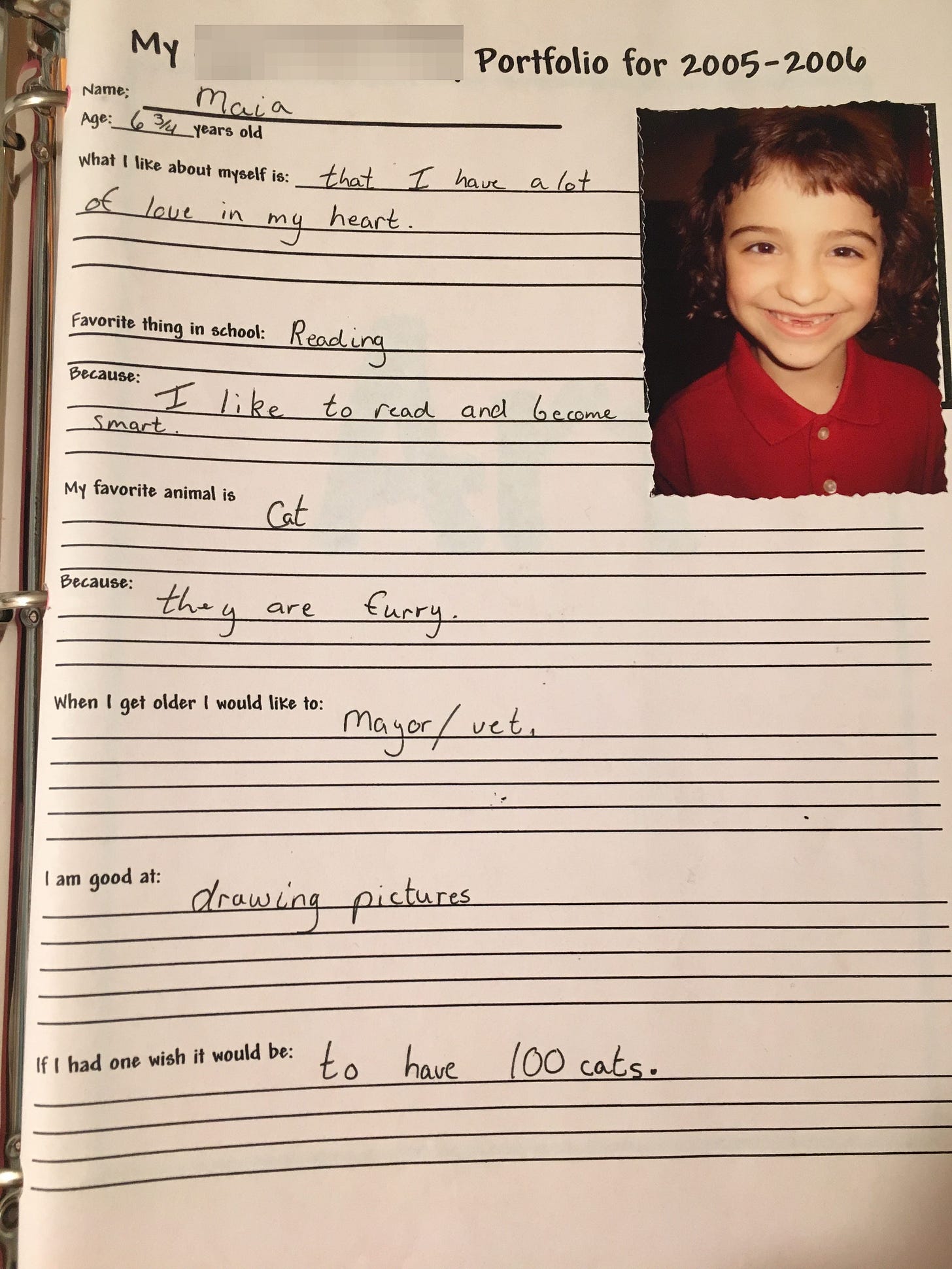

My parents recall that starting from infancy, I’d have meltdowns if not allowed to pet the neighborhood cat before nap time. The older I got, the more obsessed I became with cats. Shortly after this picture was taken, I had memorized the names of dozens of breeds of cats (and dogs) based on a poster hanging up in our house.

Every year for my birthday, or for any occasion where I’d have family visit me from foreign countries, I would beg for them to bring me another stuffed animal cat toy. Over the course of my childhood, I managed to collect 369 of them. Until I was 13, I believed my toy cats had feelings and that I needed to acquire more cats so they each had a friend. I didn’t really have the toys engage with each other, but I did collect them, arrange them in specific ways so as to ensure that none of my toy cats were alone. For those who are wondering, yes, I do still have my cat collection. And yes, some part of me still irrationally projects emotions onto them, even though I know they are not sentient. Crucify me.

I was far more concerned that my toy cats didn’t have enough friends than about the fact that I didn’t really have friends. I found many casual acquaintances, often within one of the other Russian-speaking kids at school whose parents my parents liked. I also had some acquaintances within some of the kids who had obvious special needs: one of them was hooked up to a breathing machine, another had diabetes, another underwent constant leg surgeries and used a walker and a different one was labelled a ‘crybaby.’ Some of these kids were more enjoyable to be around than others, but I more so hung around them because I felt sad that they were alone. None of these kids were fascinated with either cats or with rare brain tumors like I was, so our connections never really became deep friendships. And for years, I was fine with that.

One of the schools I attended was so politically correct that we couldn’t even say the “e-word” (easy) for fear of hurting another kid’s feelings, where we had to invite the entire class to birthday parties or risk being publicly humiliated by our teachers afterward, and where we were required to call one another “friends.” Naturally, I came to believe that a “friend” was just any annoying kid whom I had the misfortune of sitting next to in class. I only learned in high school, that a friend is, as a baseline, someone whose company you actually enjoy.

Until middle adolescence when my parents taught me this skill, I didn’t understand how to have a conversation. I did understand how to perform a monologue– in two languages. Adults saw me as precocious and sociable. I was so sociable, in fact, that I’d wander off with random families on the beach as a toddler and chat them up as if we’d known each other for years. “Verbally advanced” was the word most often used to describe me in assessments done in my early years to screen me for developmental delays following my premature birth.

My parents would drop me off at school and I wouldn’t cry. I’d just run off and find the one or two repetitive tasks I enjoyed and do them on repeat for the entire year. At my Montessori pre-school, as the other kids jumped from station to station, eagerly awaiting to try a new activity, I dreaded moving away from my table- wiping station, unless it was to go to the only other activity I enjoyed: cutting pickles into pieces and sticking toothpicks inside of them for after nap time. My preschool teacher told my parents “never in all my years of teaching have I ever met a child like Maia” and she did not mean that nicely.

At that parent-teacher conference, my parents realized that they’d wasted valuable money on an education which was so unstructured that it allowed me to never have to explore a topic or task outside of my rigid interests.

There were other signs. I got botox injections in my legs and wore leg braces as a kindergartener, due to a diagnosis of “idiopathic toe-walking”-- which means “you’re walking on your toes and we don’t know why.” I was more concerned that the doctor who had given me options of designs to pick for my leg braces which included a pattern with cats, ended up not having the cat pattern in my size, and about how those leg braces would pinch me as I walked, than about the fact that I was the only kid wearing leg braces.

I spent so much time in speech therapy for god knows what speech problem. I had a strange, persistent inability to swallow liquids properly, without suckling on them like an infant until I learned the skill in speech therapy in my first year of high school. I struggled to tie my shoes until I was 14. Those are only a few of my most notable developmental “glitches.”

Despite my constant visits to different doctors, therapists and specialists, no one seemed to notice that I went through life fundamentally confused. I thought emotions were just the early 2000’s emoticons adorning classroom walls, rather than connecting them with the sensations you felt in your body when you or anyone else made those faces. And yes, I thought anger might actually turn your face red and make steam come out of your ears because I saw it in a picture.

As a kid, the only emotions I had a surface level understanding of were “happy” and “sad.” I always tried to make other people happy, even at the expense of myself— because I didn’t realize that I could just tell another kid “NO” when he or she wanted to take (not share) one of my beloved toy cats, so I just hid them away. I did not begin to understand how emotions worked until I began to study neuroscience as a fun little hobby, an understanding which I began to consolidate probably last year when I finally studied them in a therapeutic context.

I’ve always struggled to read the room, and in many ways that saved me. Based on the laws of childhood, kids like me should have been bullied mercilessly, but because I couldn’t pick up on passive aggression, I didn’t even understand that I was being excluded. I ran around between different groups of kids, tried to maintain amicable relationships and became extremely popular with kids in my grade, despite having no friendships beyond a bunch of acquaintances. I didn’t even notice that other kids grouped themselves into friend groups until my brother started having his same three friends over at the house all the time. I had no idea how to actually play with my peers, so I usually preferred to talk at my teachers during recess.

Yet, no one ever stepped back and asked whether there was a deeper reason which explained how both my quirks and extreme gifts, and my profound delays might be happening together. Doctors and therapists chalked it all up to my being born prematurely, even though prematurity couldn’t explain all of my difficulties, especially as I got older. Each issue was treated in isolation—toe walking here, speech issue there, social confusion somewhere else. A cohesive diagnosis for these issues was never explored, either because the problems didn’t seem to my doctors to belong to a single category, or because each problem required a different specialist. Quirks of mine that weren’t urgent problems got missed, because, well– being a toddler with odd speech patterns and unique expressions is hardly a cause for concern when the same child went from not crawling to walking on her toes.

There was no unifying framework to explain to myself or to my parents, the type of challenges I would face in life. Thankfully, my tiger parents were able to mitigate many of those concerns even without such a framework, due to their highly proactive and competent parenting. Their proactive parenting also made it hard for teachers and other adults to understand the extent to which my learning issues and general confusion about how other kids work, really was pervading my life. In any case, I spent most of my free time in childhood being shuttled between doctors’ offices, physical therapy and extra tutoring. I knew I was different, at least from my brother, who got to spend his free time playing fun games instead of playing developmental catch-up. I knew I was different, and as I got older, I needed to find out exactly why.

The “Trickster” Diagnosis

One day around age six or seven, I remember sitting in the cafeteria at school. My dad had promised he’d get me a muffin. When he handed me a brown McDonald’s paper bag, I opened it to find a breakfast sandwich instead, the sandwich was called an “Egg McMuffin.” Needless to say, my expectations were violated. I was devastated. I had been looking forward to that muffin all morning—probably just two and a half hours, if we're being honest, since lunch was at 10:30 a.m.—but to me it felt like eternity. I felt pressure build behind my eyes, a searing tension that moved through my body and settled beneath my eye sockets. Instead of crying, I began to pull out my eyelashes.

This became a common practice. Whenever I was overwhelmed—by itchy tights, a tag in my shirt, my expectations being violated, the flicker of fluorescent lights, or the sound of twenty pencils scratching paper at once—I would pull out my eyelashes. It was the only thing that helped soothe me. Something like the flicker of a classroom light, which other kids could tune out, would make me leave my body. But I didn’t throw tantrums. I didn’t yell or flail. I sat quietly and regulated my internal chaos in the only way I could.

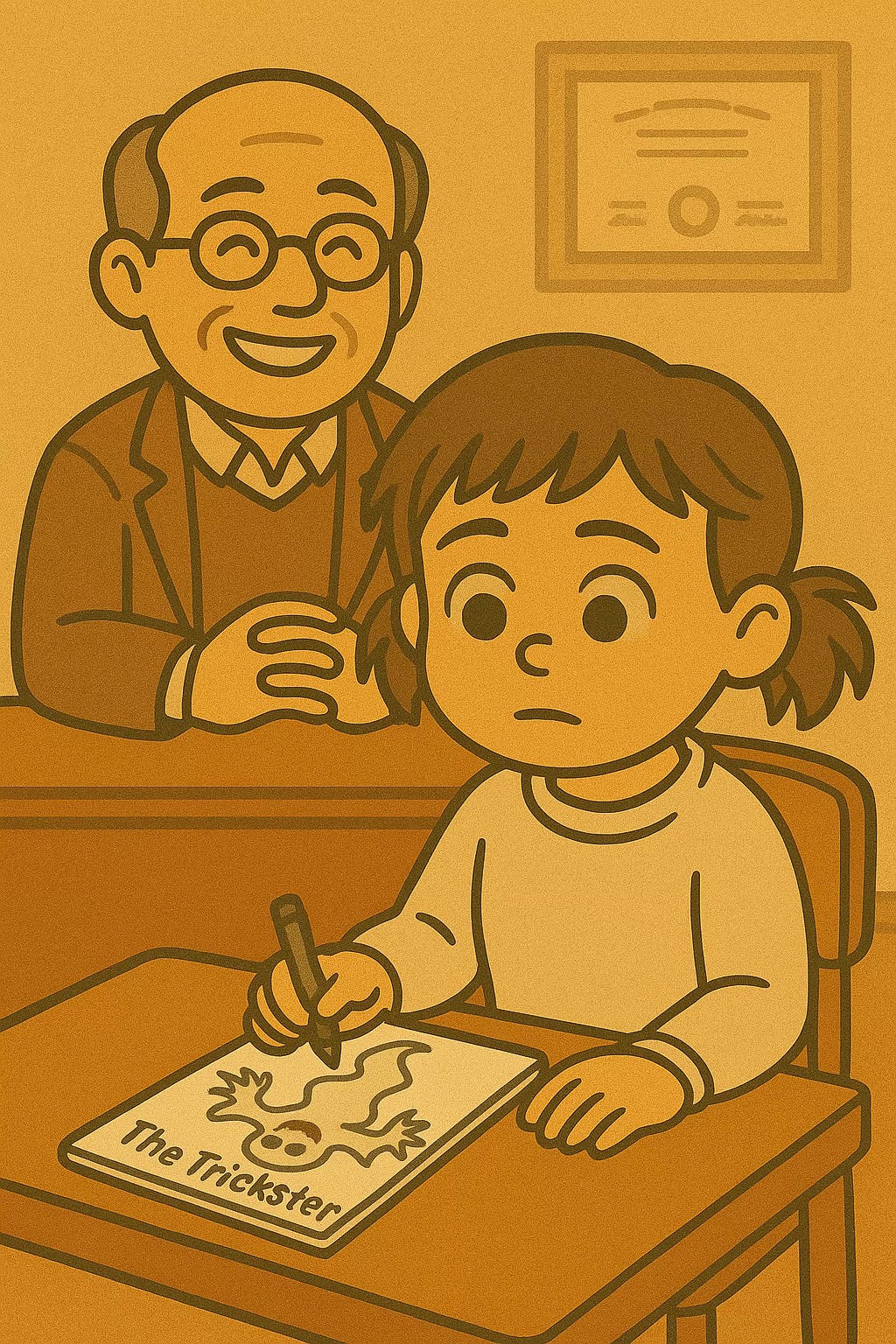

Eventually, I found myself sitting in the office of a psychologist named Dr. M. He had a large brow ridge, big eyes, and was completely bald. He smiled often, in a way I found somewhat unnerving. During the initial part of our visit, I stared at his eyes. I had just read in a book that eyes stop growing around age seven, and I wondered if his eyes had really always been that big. Meanwhile, he and my mom talked about things that bored me so thoroughly I could barely remain in my seat.

Then Dr. M turned his attention to me. He told me that the reason I was pulling out my eyelashes was because I had a “trickster” in my brain—a little being who was tricking me into doing it. I remember feeling completely confused. His explanation made absolutely no sense to me. He handed me a small yellow notepad and said, “Maia, can you draw the trickster for me?” I didn’t say, “Dude, I don’t know what the hell you’re talking about.” I just realized this was a great prompt to draw a creative picture—which I already loved spending hours doing at home to tell stories before I could write—and a good way to satisfy him so I could leave. I constructed an elaborate image of a half-ghost, half-monster floating around the page. I had great fun drawing the trickster, but I certainly emerged with no more insight into why I pulled out my eyelashes. I didn’t believe anyone or anything was tricking me. I did it because I liked it. Because for whatever reason, it helped.

After that, my parents became the eyelash police. They began bribing me for every day I didn’t pull. I’d get a little toy or knickknack for each successful day. When I came home from school, they’d examine my eyelids and express their disappointment if I’d failed to resist. Other parents noticed and commented. It was treated like a moral failure, or like a bad habit I needed to outgrow. No one saw that I had no control over it. It was what I did when my body reached a threshold of tension I couldn’t tolerate.

When I was nine, we took a class field trip to a food bank. In theory, I was excited—we were helping people in need. But when we got there, everything went wrong. The fluorescent lights were gigantic. We had to sort dry beans into plastic bags while wearing oversized plastic gloves. My hands got sweaty; the gloves stuck to my skin. The sound of beans rattling, of voices echoing through the large space—it all became unbearable. I felt that burning tension again. I wanted to leave, but I knew I couldn’t ask. I couldn’t make a scene. So I pulled out my eyelashes. I knew that if I wanted to participate in this altruistic task which proved to be an all out assault on my senses, I had to do something to steady myself. When I got home and told my parents about the field trip, all they focused on was their disappointment that I had pulled out so many eyelashes I had moved on to my eyebrows.

Looking back, I understand why Dr. M used the trickster metaphor. I’ve since read enough parenting books to know that developmentally, kids hate being tricked—and fear of trickery is often used as a tool to explain compulsions. But I wasn’t like the other kids. I didn’t care much about being tricked. I didn’t even like tricking others. I never saw the point. Magic tricks didn’t delight me; they usually made me anxious. I remember watching a magician appear to saw a woman in half on a televised talent show. The audience clapped. I sobbed. I thought he had hurt her. I didn’t understand why people were cheering for someone causing pain to another.

I was diagnosed with OCD—on the sole basis of my eyelash pulling. But what I was experiencing in all likelihood an autistic response to overwhelm, to disappointment, to the world being too much and not making sense. My scripting, my toe walking, my sensory sensitivities, my hyper-verbalism paired with social confusion—none of it was considered together. Each trait was filed into a separate folder. But no one ever thought to ask what tied them all together, because why would they?

This is how autistic girls get missed. We don’t scream. We don’t throw desks. We build ghost-monsters and draw them on notepads to satisfy the demands of some odd looking psychologist so we can go home and be with our toy cat collection. We adapt. We internalize. We cope quietly. And when we do express distress, it’s interpreted through frameworks that don’t address the root cause. I didn’t fit the model of high-functioning autism, or Aspergers as it was called when I was a kid— because I was a girl. So I fell through the cracks. And as I got older, I had to build the model myself.

The Diagnosis Shelf

Most Gen Zers began diagnosing themselves with mental disorders sometime around the mid-2010s—but I was already doing it before I was 12, and even before I was regularly online. I’ve always been fascinated by pathology—whether it was rare brain tumors or neurodevelopmental disorders. As a small child, I enjoyed having my parents read me fictional books, though I cared less about the stories themselves and more about memorizing them word-for-word to harvest sentences I could use in conversation with other children.

The moment I had to read for myself, I gravitated toward non-fiction—pop psychology articles, parenting books, and eventually, medical journals. Instead of obsessing over TV shows or pop culture icons, I became obsessed with a new DSM diagnosis every week (or month), back in the days of the DSM-IV.

I first used the word “neurodiversity” around Christmas 2011, after my grandma gave me a book by that title. We’d just spent my birthday at the bookstore picking out books about children with hyperlexia. I even volunteered with a little boy—also tutored by my own tutor—who had both hyperlexia and autism. For my 11-year-old brain, this was a jackpot. I was the only seventh grader I knew who regularly asked, “I wonder if we can find autism in the brain.”

When the DSM-5 was released, I begged my parents for it as a birthday gift. They refused. “We probably already have the 4 at home,” my mom said. “That sounds expensive,” my dad added. I was disappointed, but I couldn’t exactly complain—kids my age were upset about not getting the latest video game console. I think I settled for Heelys that year instead.

My parents might’ve gotten me the DSM-5 when it came out when I was about 13 or 14, if they hadn’t been worried I was becoming a hypochondriac—it runs in the family. The irony is, I was a stickler for diagnostic criteria. I wasn’t just assigning myself random conditions. I analyzed the criteria closely, tried to attribute my behaviors to them as closely as I could, and I was usually right.

But let me back up.

A few months after my tenth birthday, I began to attend a public school. Unlike in my previous school, where virtually all the kids were either the children of highly successful immigrants or kids with tons of autistic traits whose parents refused to get them diagnosed—and where we weren’t allowed to say the word “easy” because it might hurt someone’s feelings—the public school kids were cursing, eating junk food, and had never even heard of War and Peace. I realized pretty quickly, not only because I wrote in cursive and didn’t know how to write in print, but for every other reason, that these kids were very different from me. Mostly, because they wouldn’t tolerate my lecturing them about my favorite brain tumors.

My obsession with neurological conditions and, eventually, self-diagnosis started around my eleventh birthday—with one inconsequential utterance. It began on a Friday night when I was around ten (and a half) years old. I woke my parents—gently shaking them, restless and bored—saying, “Mom, Dad, I’m bored.” Half-asleep and desperate for silence, they told me, “You’re a big kid. Go to the basement, find a book, and read it.”

I took their advice literally. I walked downstairs and spotted a lonely book gathering dust by my dad’s old slippers. It wasn’t shelved with the others, and I remember feeling bad for it. Why was it all alone? Why wasn’t the book with its friends? I picked it up out of pity and settled into the basement couch.

I’d recently grown bored of my human genetics obsession and had tried to revive my acromegaly (otherwise known as ‘gigantism’) obsession phase—but nothing really stuck. I wandered between obsessions like an oasis of predictability. I always needed something to master, something to understand completely. It wasn’t just about plain old curiosity—it was a survival structure I had adopted to navigate a thoroughly unpredictable world that I struggled to make sense of through normal interaction and play. I felt lost and lonely whenever I fell out of love with a topic. My parents probably wished I’d become obsessed with schoolwork, but nothing at school remotely interested me.

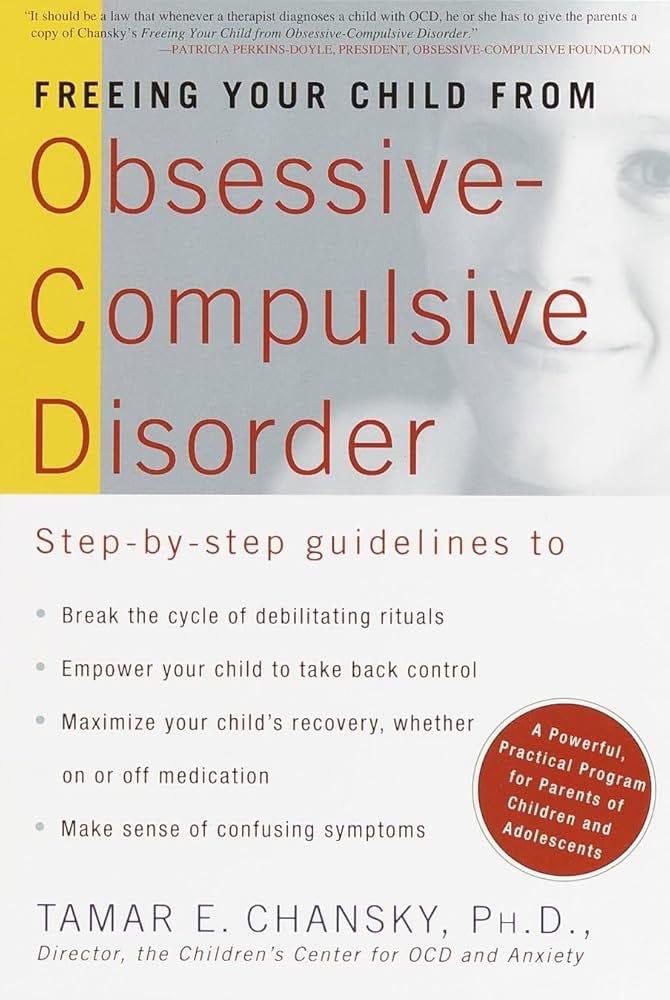

The book was called Freeing Your Child from Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Within a few pages, like any almost eleven year old to ever grace planet Earth, I was hooked.

For the first time, I encountered the idea that behaviors could be “typical” or “atypical.” At this point, I didn’t realize just how different I was from other kids, even though I showed up to school carrying a test tube of extracted cow DNA to show my classmates. Because I spent so much of my free time in doctor’s offices and tutoring sessions, this book offered an easy to understand framework for a fifth grader, to name and make sense of those differences. I also learned something I’d never considered: that parenting required strategy. Until then, I hadn’t thought about why kids even had parents. They just did. It wasn’t until after I saw childhood photos of my own parents that I realized that they used to be children. But here, in my basement, was a manual explaining how adults could interpret, redirect, and respond to children’s behavior in ways that helped them grow. That manual could also be of use to me, as I attempted to understand the odd behaviors of my peer group. At first, I was convinced they were the weird ones. The more I read, the more I realized I was the weird one.

I read it obsessively and finished it within days.

Months later, I found another book in the basement—another parenting book about OCD—and read it cover to cover. That’s when I first learned the name for the eyelash pulling thing I was doing: trichotillomania. It was listed as one manifestation of OCD. The book said you needed more than one symptom to qualify for a diagnosis, and I only had that one. So I kept looking to see if maybe that’s what explained why I was so different. The book mentioned that OCD and trichotillomania often co-occurred with ADHD. I read the brief description in the OCD book about ADHD and became newly transfixed. The next morning, I begged my parents to take me to the bookstore so I could start reading about ADHD. Those books also mentioned autism. I didn’t fully understand that part yet, but later, when my mom gently pointed out that I wasn’t picking up on social cues, she began teaching them to me directly. That’s when it started to click.

The concept of “comorbidity” became part of my vocabulary—probably more confidently than any other ten year old alive (I was almost eleven— I am saying this because at that age I would have cared). ADHD, autism, dyslexia, hyperlexia—each new label, each new comorbidity latching onto the last, opened up entire worlds of systematizing analysis by which to categorize the behaviors of people. These diagnostic criteria offered me more than just categories; they told me that patterns existed, that brains could function differently, that behaviors had meaning—even though no one had explained them to me that way before.

This wasn’t just a new obsession. It was a mirror of sorts.

I didn’t see myself in most of the OCD parenting books, though I did clearly see other members of my family in them. Apart from eyelash pulling—which had led Dr. M to diagnose me months earlier—the rigid rituals, intrusive thoughts, and compulsions didn’t fit. I concluded OCD wasn’t the right explanation. But that book had introduced me to a whole library of labels—a diagnostic framework that soon became my private obsession.

I asked my parents to take me to the bookstore to find more books about ADHD. ADHD captured the chaos in my head: my inability to focus on anything I didn’t care about, the mental ping-ponging of ideas. The word “Autism” showed up again in those books, but I was too interested in learning about the three splinter types of hyperlexia (abnormally early reading) to move on from that condition just yet. It wasn’t until a couple years later, my mom realized that I was not picking up on social cues and decided to teach them to me on flash cards that I began to see myself in that framework too. Over the course of my life, I began to realize all the things adults had treated as isolated issues—my swallowing problems, leg braces for toe-walking, not tying my shoes until fourteen, one-way monologues—were not separate at all. They were signals of an underlying structural neurodevelopmental condition. But no one had named it. The name for that condition would become the greatest pursuit of my life from age ten until today, at the age of 25.

Even before I had my own internet-connected device—my 12th birthday gift—I was already going down rabbit holes, page by page, book by book. My brain needed to find order. I needed to make sense of why I was different, why the world seemed to make sense to other people but not to me.

The power of neurodivergent ADHD and autistic fixation can be so intense and all-consuming that a person will live and breathe their topics of obsession. That’s exactly what I did. I lived and breathed understanding, first those around me and then myself. I thought I was studying disorders—but I was really studying myself, through the lens of pathology. It was the only way I had to understand why I wasn’t like other kids. I spent so much time going from one specialist to another that long before I identified as trans, I’d already internalized the belief that something was fundamentally wrong with me.

My parents were hesitant to accept the diagnoses I proposed to them eagerly. I wanted to prove to them that despite my learning challenges, I wasn’t the colossal idiot I considered myself to be. But, because hypochondria runs in our family, my parents became concerned by my diagnosis obsession being a sign that I too was developing the condition. In retrospect, I can see why they were so concerned: I interpreted the embodied sensations of my first crush as symptoms of a disease and had my parents take me to the doctor to get tests done, which showed I was healthy.

My parents initially dismissed my self-assessment of ADHD as something I merely had "traits" of—something they had already been determined to coach me through with grit and repetition. I notified them that I had highlighted the traits I had of this condition, and showed them that I had more than enough to meet the criteria for a diagnosis. My learning issues didn’t just appear around that time– they were an everpresent feature throughout my life. If my lessons at school weren’t about writing, reading or rare brain tumors– I simply was not interested enough to pay attention for longer than is needed just to glean a sentence or two about the subject matter to convince my teacher I’d been paying attention if she did call on me.

My mom and I would stay up studying past midnight every single night, just trying to keep me caught up on the lessons I should have learned if I had just paid attention at school. My mom would always tell me “It might take you ten times as long to learn this as it will for the other kids, but you just have to stick with it.” I wasn’t sleeping enough because of how much I needed to study just to stay afloat. I wasn’t getting better. I thought I was a colossal idiot. I was deeply convinced I had a severe intellectual disability, while trying to continuously prove to myself and to others that I didn’t. I needed to find an explanation that my parents might actually believe in. I needed a framework that explained why I was so different from my peers—and why I wasn’t becoming more like other girls; more into my appearance, why I didn’t experience ineffable romantic feelings for boys, why the thought of having long hair for the rest of my life made me want to pull out my hair again, why I couldn’t stomach the thought of wearing revealing clothes and make-up like my peers had been begging their parents for. Really, I was confused as to why none of the girls in my class made sense to me and about why whenever one of them smiled at me, I experienced an inexplicable raised heart rate as a warmth overcame my body and other odd feelings I didn’t understand.

That framework, of course, was the transgender framework.

It explicitly answered the question, “Why am I so different from other girls?”—and it gave me an exit. In retrospect, my embracing that identity should have been the clearest signal that something deeper needed to be explored. But instead, it was treated like a catastrophe to be shut down—rather than a clue pointing toward a larger web of confusion, distress, and unmet needs.

There was no help for my parents. No therapist understood what was going on when, in 2012, a 12-year-old girl said she wanted to be a boy. So it got shoved under the rug.

When my parents shut off my internet in an attempt to cut off my gender fixation, it didn’t stop the obsession—it just punished me for my earnest but misguided search for the truth. What I needed wasn’t more restriction. I needed guidance, some critical thinking skills, and calm exploration that could have lead me to the very truth I was desperately pursuing.

Instead, my obsession went underground. I returned to the internet at school, to point me toward bookstores and printed material—just like I had done with OCD, dyslexia, hyperlexia, and ADHD. I couldn’t understand why my parents were so upset at my finding a framework to understand myself, even though they disagreed with my conclusion. I already told them that I thought I had ADHD— they disagreed, but they didn’t punish me over it by cutting off my ability to obsessively research the latest, greatest ADHD brain wave theories. My transgender obsession wasn’t just an intellectual one anymore. It became fused with the developmental drive of adolescence: to define who I was and to find my place in the world. It became personal. And I became hell-bent on pursuing the one framework for understanding myself that I knew would someday, force at least someone— if not my parents, maybe a doctor— to finally understand me.

The result of this forbidden gender fruit obsession? I couldn’t think about anything else. My learning issues, which were already overwhelming, worsened. I could focus even less in school. My academic decline, accelerated due to my fixation I had to keep secret— pushed my parents to finally seek an assessment that summer.

That assessment—though its findings were black and white—brought no one any clarity, though in my opinion, it should have. In my next essay, I’ll show the results of that assessment to explain how easy it is for the “experts” to miss autistic traits in girls, even when the results scream “something is really unusual here.” The results of that assessment only deepened my confusion and by the age of 14 led to a new diagnosis. It wasn’t autism—but it came closer to the truth.

How Does Autism in Girls Get Missed So Often?

The systems built to recognize and diagnose neurodivergence weren’t designed with girls like me in mind. They were designed for loudness, disruption, visible distress. But girls like me cope through silence, through intellect, through internalization. We learn to perform what the world expects, even when it doesn’t fit. Some of us succeed at this more than others. We adapt until our adaptations hurt us. And when the distress finally leaks out—through compulsions, through identity confusion, through a growing sense that something is deeply wrong—it’s usually interpreted through the lens of everything but autism.

This isn’t just a failure of individual practitioners—it’s a structural flaw in the diagnostic frameworks themselves. The criteria for autism were built around how traits typically manifest in boys: externalizing behaviors, overt social difficulties, and clear, observable fixations on (usually) mechanical objects like trains or computers. But autistic girls often script their way through social encounters, imitate peers, and present as “well-behaved” while struggling intensely beneath the surface. Our special interests might look socially acceptable, or be seen as so advanced that surely our other developmental ducks are in a row. Our distress might look like daydreaming, anxiety, or even perfectionism. So we get missed, misdiagnosed, or labeled with fragments—OCD, anxiety or if we’re lucky, ADHD (at least this one is a neurodevelopmental diagnosis)—without anyone asking what ties it all together.

The “trickster” wasn’t in my brain—it was in the diagnostic frameworks that kept changing shape every time I tried to pin them down. I wasn’t being tricked by a monster in my head. I was being missed. And like so many other girls with a preponderance of autistic traits, I ended up creating a map for myself because no one else could hand me one. And I needed a map, because without it, the world made no sense.

It’s time we start giving girls like me a different map than the roadmap to lifelong trans techno-medical destruction—one that sees their struggles not as scattered quirks or character flaws, but as clues pointing to a deeper, coherent, and very real neurodevelopmental difference. When we more accurately, expand our vision of what autism looks like in high-functioning female children especially—we give these types of intellectually gifted and socially delayed girls the chance to understand themselves before they reach for the wrong framework. We give them a language to claim their difference without having to pathologize it by reconstructing their identity on the basis of a lie.

And maybe, just maybe, we prevent them from mistaking a ‘mask’ for a mirror.

A Note on My Perspective and How I Can Help:

Parent Coaching with Maia Poet

Are you navigating a confusing or painful chapter with your child— around gender identity, emotional dysregulation, or a growing sense that something deeper about your child is being missed?

I offer one-on-one coaching sessions for parents who want to respond with clarity, steadiness, and insight—not panic, shutdown, or blind affirmation. As someone who went through a gender identity crisis as a child, misdiagnosed and misunderstood, I now work with families to make sense of the bigger picture: what your child is trying to communicate, what’s being overlooked, and what you can do to lead with compassion, authority and a clear plan.

In our session, we’ll look at your child’s behaviors, communication patterns, and underlying needs. We’ll zoom out from isolated incidents and start connecting dots—sensory sensitivities, social struggles, identity fixation, anxiety cycles, academic collapse, or emotional overwhelm. We’ll make a plan tailored to your family, grounded in curiosity, boundaries, and a developmental approach.

Though I can’t offer therapy, I can offer insight-based coaching. You come with questions, I come with insights garnered through my personal experience, clarity, language, and you can leave with a strategy, and with the beginnings of a workable plan for how best to help guide your child through this period of their lives regarding gender questioning and neurodivergence. In my sessions, we work together to reclaim your role as the parent—and help your child come home to who they are, so they can become the best versions of themselves, without getting stuck in who they think they have to be.

Let’s think this through together.

In any case, stay tuned for parts two and three of this essay, where I delve deeper into my story and what I think diagnosticians and parents alike should understand amidst the increasing discourse about both autism in girls getting missed, and about the overlap of autism and increasing rates of gender dysphoria diagnoses.

Did You Enjoy this Essay? Does my work teach you things?

If so, please become a paid subscriber to support my work, so I can continue bringing my insights to you. My essays take a lot of time and effort to produce and to bring to you. As a 25 year old independent writer, your $8 a month is very much appreciated.

Maia’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber by clicking on any of the buttons in the post.

Do you have a kid navigating gender confusion and trans identification?

If so, I offer parent coaching sessions to help you figure out how to best navigate your specific child’s situation, in a compassionate and practical way. If this is of interest, please DM me.

You are fascinating. I appreciate the detailed explanation of your life. The misdiagnosis is incredible. I’m 66 and was a female engineer (male dominated field) so I understand that people treat us differently with the same “symptoms” (behaviors) as boys/men. You are amazing to have figured out so much and I know it will help others. Thank you. I look forward to further installments

Greatly enjoyed. If you haven’t (I suspect that you have from your use of the word “systemizing”), you (all) should read the works of Dr (Sir) Simon Baron-Cohen, head of the Autism lab at, I believe, Cambridge. In one of his books, he mentioned that ASD presents differently in females, and, is much harder to diagnose as a result. I asked him for some books on the subject, and he kindly obliged. A light went off in my head after reading them. A loved one now made sense. Which is good because I can take remedial steps, in case of, for example, over-stimulation.

Her story was somewhat different from yours. She was in braces at a young age, because she was pigeon toed and flat footed. Didn’t work, so eventually her mother threw them away, and put her in toe shoes - at maybe. 3-4. That did work. Got rated as Retarded because she wouldn’t talk in school. She was plenty verbal at home, but had nothing to say to teachers who refused to pronounce her name correctly. Ended up in Special Ed, for a year, and hated the boys pulling her hair all the time. So vowed to get out of school ASAP. Graduated HS at 15, took a year at floral school, before she was allowed to start college.

Comparing you to her, one of the things that jumped out at me is how different the savant abilities are with different people on the ASD. She isn’t the voracious reader that you are, but is a world class colorizer. Sped through school with a photographic memory. Was a top dancer and model in college, but could never comfortably let a guy put her up in the air, which is required for prima ballerinas.

Mentioning scripts, it got me thinking. A decade or two ago, I mentioned to her that women bond by complimenting each other. It didn’t really matter what you complimented them on. So now, it seems like she can’t walk by strange women without complimenting them on what is to me, the stupidest stuff. It works.

Finally, she can detect autism and ASD at 20 feet anymore. No doubt, you probably can too by now. She just has the advantage of living with it for 40 more years than you have.