I'm a Detransitioner. Stop Sending My Essays to Your Trans-Identified Kid.

Here's why it'll probably backfire and what you should do instead:

Note: the play button at the top is not a decoration, it is a recording of me reading my essay.

Also Note: If you’re a listener, make sure to check out my fun little cartoons throughout the essay. This essay took me so long.

My Essays Aren’t For Your Kid. They’re For You:

I write essays for you. The parent. The one pacing the kitchen at midnight, panicked, Googling, scrolling, praying for answers. I write so you can start to make sense of something that probably feels senseless—so you can understand what your child might be going through, and what it might mean, without drowning in ideology or abandoning your instincts. I also write for therapists who wish to take on cases of gender questioning young people and who would benefit from my insight— or for anyone who is interested in exploring the mindset of one young person who got into this at the age of 12 and stayed entrenched until the age of 24.

But I need you to hear me loud and clear: stop sending my essays to your kid. Don’t forward them over email, don’t text them to your child. Don’t print out my essays and leave them on their bed. Don’t send me DMs asking if I’ll talk to your child personally, so I can “snap them out of it.”

I appreciate that you find my work to be helpful and insightful. I know your intentions are good. I know you’re terrified, and at the end of your rope. I know you probably think there’s one thing you can say—or I can say—that will finally get through to them. You think that this is the essay, the paragraph, the quote that will crack the gender delusion, flip the switch, make them see the truth as it is. You read something which you find to be compelling and your intuition is screaming that this is your moment to persuade. But from my experience, you absolutely cannot argue a kid out of their identity. And frankly, you should not try to.

This will only get you into a power struggle. A brutal one. The only winners in a parent-child power struggle over gender identity are activists who tell children and young people that their concerned parents do not see them and do not want them to be happy.

My body of work focuses on Gen Z trends and the adolescent need for individuation—on how some young people create gender identity as scaffolding when the self feels fragile or undefined and when they don’t have the life skills to individuate through boundary-testing behaviors which don’t require the buy in of adults. I talk about how changes in parenting trends, increasingly more medicalized approaches to childhood and institutional ideological capture coalesce in such a way as to create the tense atmosphere we see today around these issues.

When you send your child my essays, or try to use me as the mouthpiece for your beliefs, you are backing both me and your kid into a corner. That isn’t fair to either of us. Unless your child is actively questioning the trans identity they had once unquestioningly adopted, on their own volition, sending your child my essays is very unlikely to work and very likely to make things worse.

If your relationship with your child is already charged—if there’s already tension, suspicion, emotional distance—and my essays are largely about how negative parent-child dynamics intensify when gender identity enters the picture, then why—WHY—would you think that giving them something I wrote would help? In what possible universe does that sound like a good idea?

Your emotional response—the urgent impulse to send them something, anything, that will shake them out of this—is understandable. But it’s not a good place to help your kid from. It’s not strategic. It’s not relational. It’s not rational. It’s not going to land the way you hope.

I’m not here to tell you all the things you shouldn’t do. I’m here to tell you why you shouldn’t do the things your intuition is telling you to do, when your intuition is based on panic rather than problem solving. I will then explain what you should do instead. This is because I want to give you better tools for how to think about the situation.

Maia’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber by clicking on any of the buttons in the post.

How Do I Know?

I know because my parents did this to me. They sent me detransitioner essays, hoping I’d see myself in them. They told me, “Look at this girl, she’s just like you.” I read the essay. And all it did was confirm that my parents had no idea who I was—and that they therefore had no authority to comment on my identity.

The girl in the essay? She wasn’t like me. Her story didn’t even remotely resonate. She described getting caught up in a friend group trend. I, on the other hand, predicted the trans trend in 2012—years before it would begin to consume my generation. Thankfully, because I was forbidden from talking about my trans identity, I couldn’t plant the idea in other kids’ minds. But the wider culture, in a few years’ time, would.

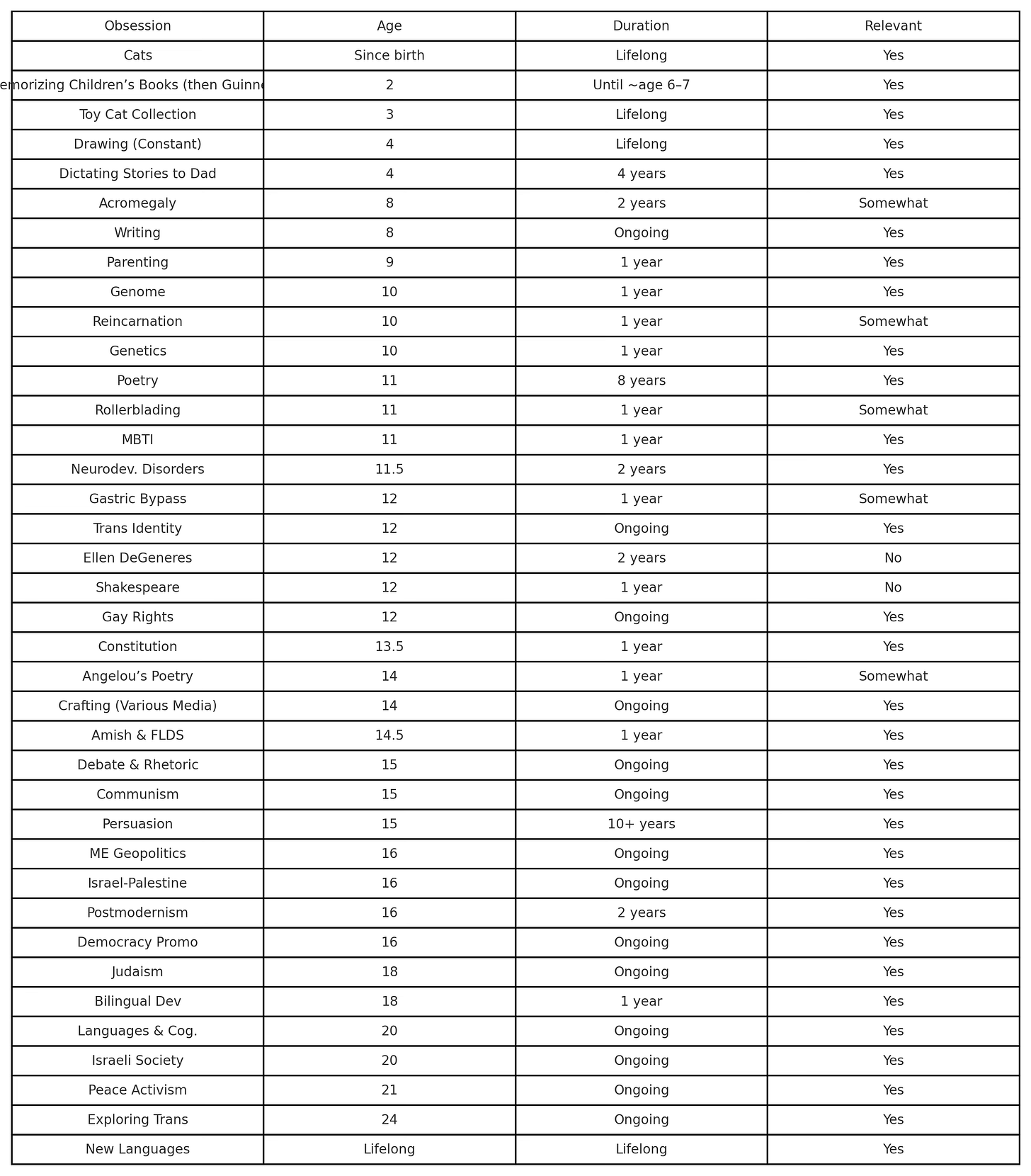

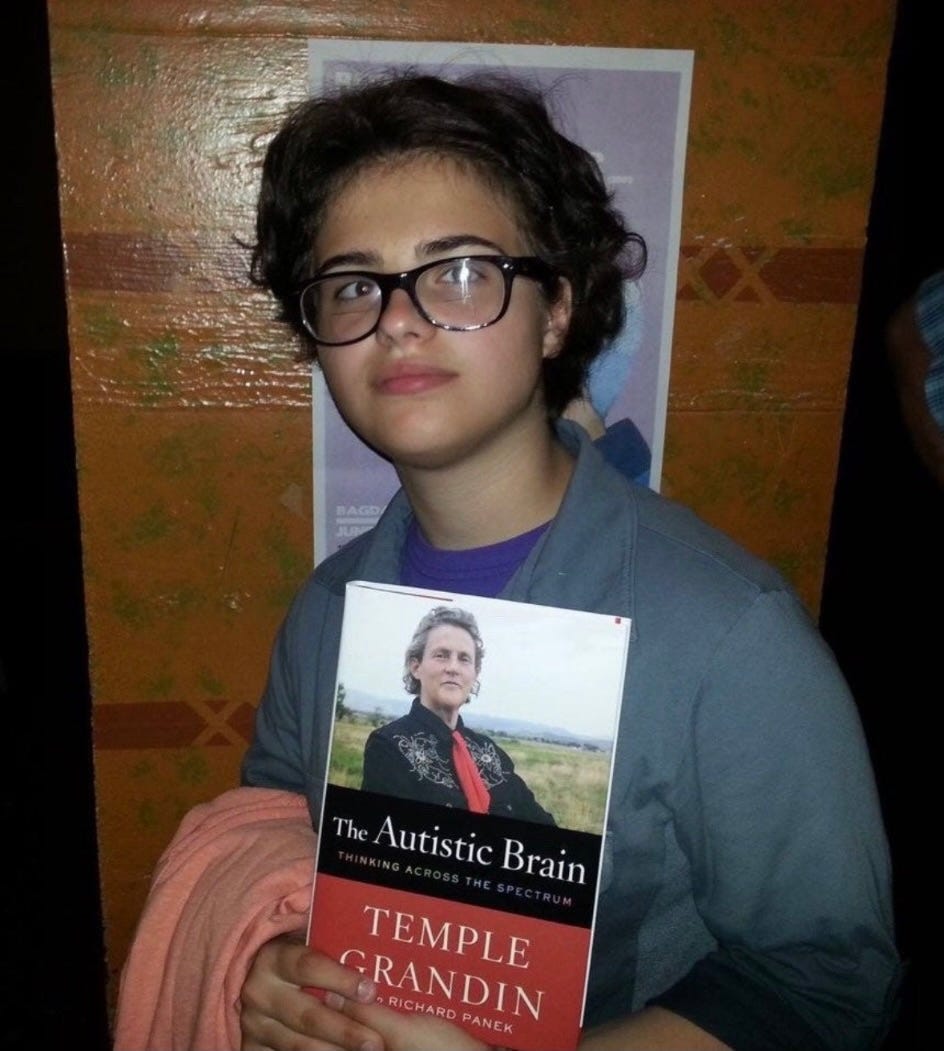

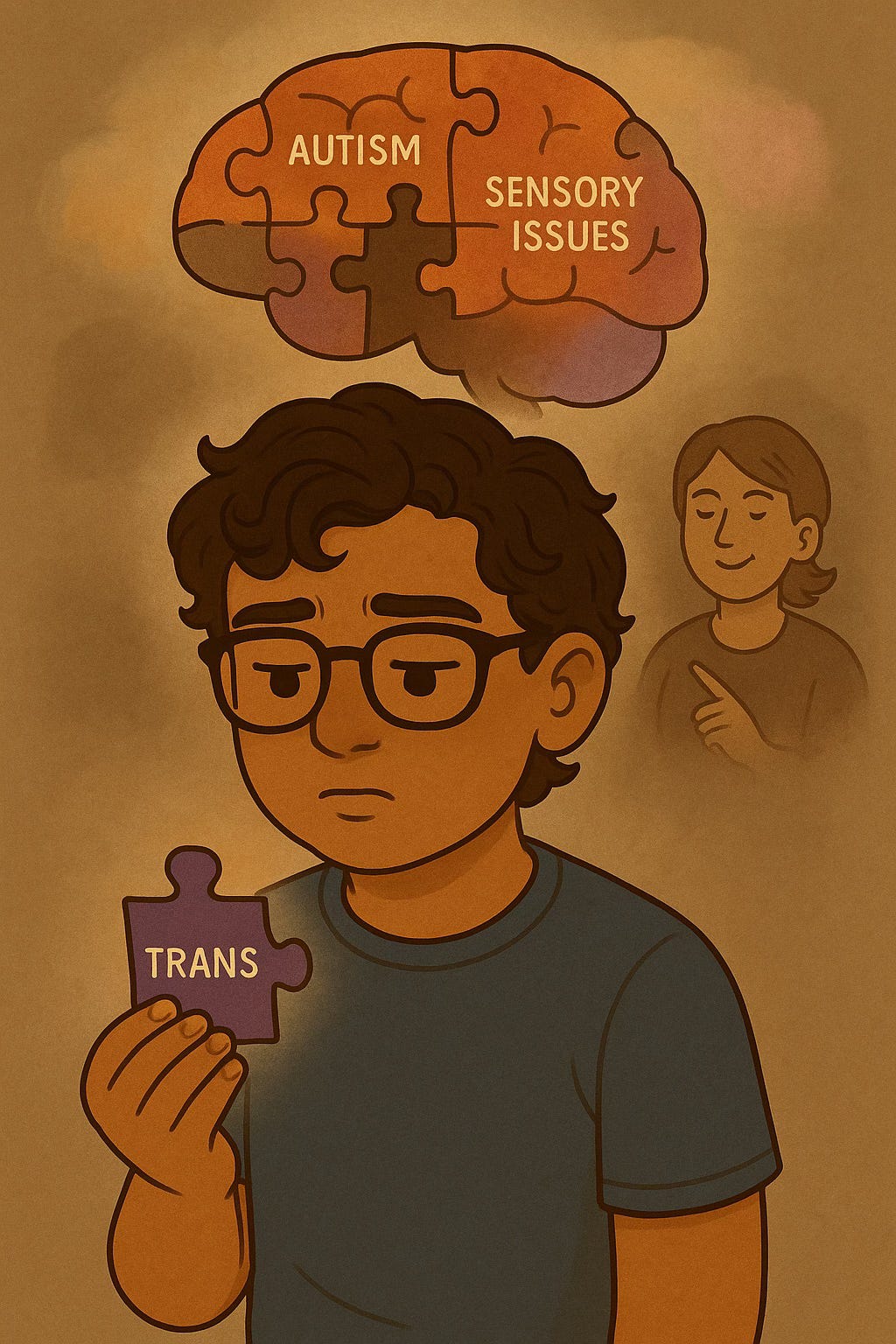

I didn’t need anyone to put the idea of transition in my head in teen-friendly, bite-sized pieces. I was already actively searching for a sense-making framework that would explain why I felt so fundamentally different from other girls. And the transgender framework wasn’t the only one I was considering. Had my parents understood this identity as just another one of my long-running obsessions with niche topics—rather than something alien and threatening—they would have been far better equipped to help me. Had I actually been diagnosed with autism, rather than just have been intellectually obsessed with it, all of us would have had better answers.

The detransitioner in the essay my parents sent me had realized transition was a mistake when she wanted to wear leggings and makeup again and felt those things were now off-limits because she had committed to “passing” as a man. A hormone-induced mental health crisis brought her this clarity, so she quit the testosterone.

That wasn’t my experience at all.

I so badly desired transition because I couldn’t tolerate the onslaught of societal expectations telling me to “grow out of” my tomboy phase far before I even came out as trans at the age of 12. I had already absorbed the message that being the kind of girl I was, was totally unacceptable. The difference between me and my female peers was obvious to anyone with one working eye—and it painfully obvious to me as well. Not initially, but because it was pointed out by so many adults, both in the West and including my relatives who still lived in a formerly Communist country, who just wanted me to conform. They were relentless.

I didn’t understand why I was so incapable of doing what everyone else did—when it came to gender, and when it came to literally everything else in my life.

I’m a nonconforming individual by nature. And ironically, once being trans became popular, I started questioning it more. Even the kind of gender journey I went on—ideation and social transition—was qualitatively different from that of my peers. I had internalized the “old-school transsexual” narrative which said that this was rare and medically indicated to resolve some kind of neurobiopsychological mismatch. I had never heard of “nonbinary.” That entire category simply didn’t exist in my framework at the time.

When my parents sent me those essays—about ten years into my trans identification—it became clear they were trying to fit my story into a framework that made them more comfortable. In those ten years, we had never meaningfully discussed the root causes of my gender questioning. We argued almost entirely about superficial appearance. They wanted to believe I had once been a “normal” girl who had never questioned her gender—until the internet got involved. They preferred to imagine I’d been on track for a life of traditionally feminine pursuits and adornments, as long as I had just been allowed to mature and with heavy guiding, to grow out of the quirks that didn’t make me successful, and that all of it had been derailed by peer contagion and woke culture.

They had stitched together two different timelines and created a story that was objectively untrue—while accusing me of reconstructing my past.

Had they asked me even a few thoughtful questions—rather than trying to squash the scary idea entirely—they likely would have understood what compelled me to adopt these unheard-of beliefs. They could have helped me explore them without resorting to forbidding, restricting, panicking. They could have seen that, like any teenager, I was just trying to answer the question: Who am I?

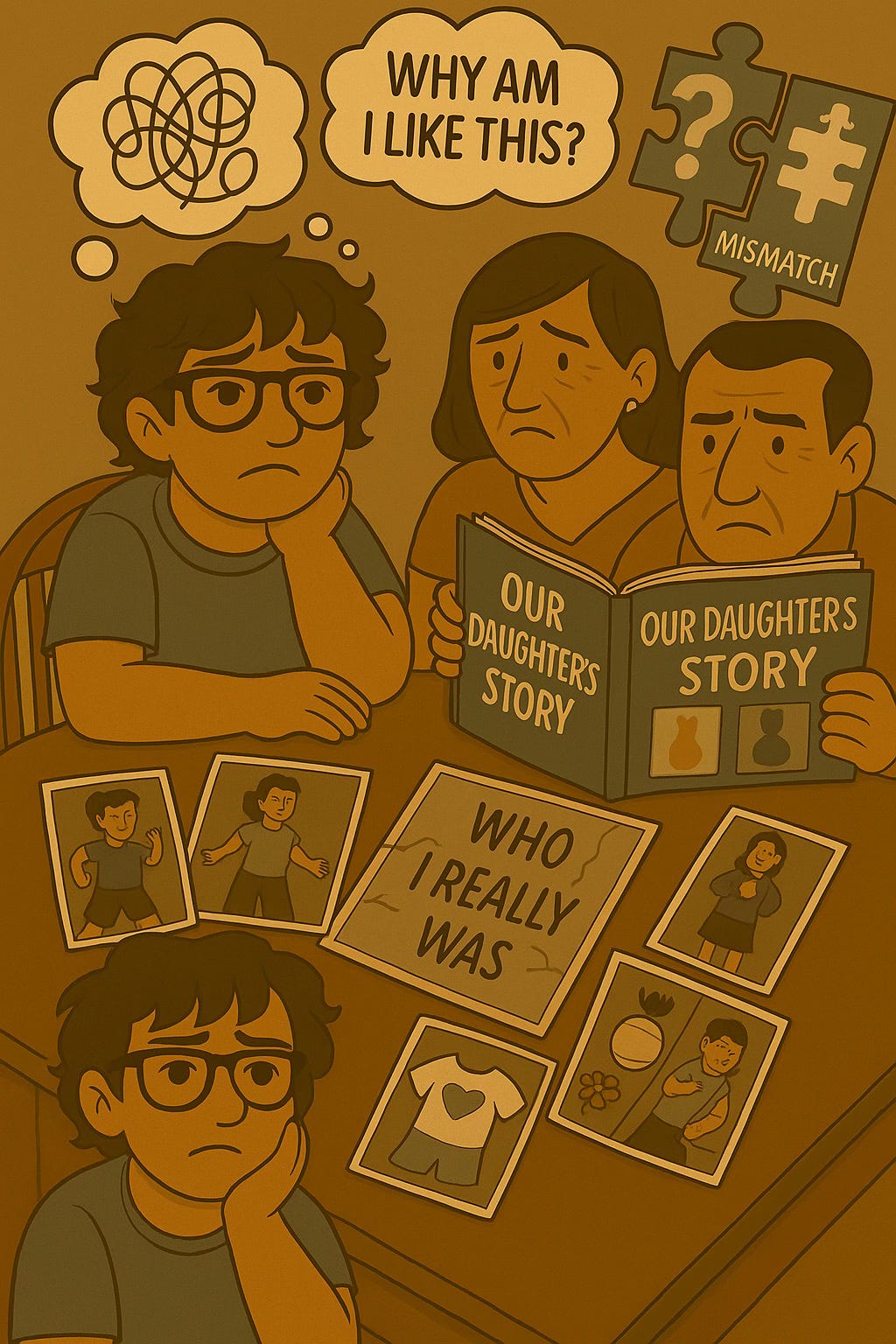

By the time they sent me that detransitioner essay, my parents had already been dealing with my gender issues for a decade. And by then, it was easier for them to superimpose someone else’s narrative onto me than it was to reckon with the truth: that I had always been different. That I had always struggled with embodiment because of my cerebral nature and sensory processing issues. That I had always felt fundamentally out of place.

Nothing about my development was even remotely typical— though it probably was typically autistic, and because I’m a girl, I never got diagnosed with the thing I actually had that could have explained me both to myself and to my parents. The truth was that I was not destined to become a typical, feminine, conforming woman. I’m simply not wired that way. I tried it for a couple years to make others happy and to see if I could stomach living like that forever, because that is what I thought it meant to be a woman. It was so miserable that I became even more hell-bent on pursuing transition than ever before— but my parents who looked for ‘clues’ within superficial clothing styles instead of asking exploratory questions aimed at figuring me out, they thought they had finally succeeded, took their eye off the ball and then I ran away to college and socially transitioned.

The truth was that I had tried to be a normal “man” because of how catastrophically I had failed at being a “normal” woman. This identity gave me a structure to cope with being misunderstood in every way—and offered me a tantalizing promise: that I could keep doing what I loved without having to change anything about myself except my body, and finally fit into society.

My parents knew I had gotten into this long before my peers. But in their panic, they flattened the complexity of my story into a hopeful narrative: the girl who lost herself for a while but eventually came back and embraced femininity. They thought that if they pushed traditionally feminine things onto me—makeup, jewelry, dresses—I’d finally feel connected to my body and enjoy “being a woman.” They had dreams for their daughter. They wanted her to be successful, palatable, socially acceptable. Not because they were bigots. But because they were scared.

They were scared that my non-conformity would make my life harder than it needed to be. This was the root of their panic. And it centered around things that were objectively not a big deal: hair, clothing, walking elegantly, tone. But it wasn’t small to me. It shaped our entire relationship. It made me feel ashamed of doing things that were natural to me and also natural to adolescents— of realizing I did not fit in, and of trying to figure out who I was. I was earnestly trying to solve a problem.

Parental panic isn’t personal, but culturally and generationally transmitted. In my case, a certain level of survival-based neuroticism was transmitted to me because I come from a partial legacy of being raised by a Jew who was raised in a Communist country— where non-conformity meant certain social death and where survival meant conformity. Immigrants don’t just become new people when they leave their homeland, and my family brought that level of fear with them to the West. In the height of their panic, it didn’t even occur to my family that a Western liberal democracy—even with all its imperfections—might still have room for someone like me. Yes, my life would be harder. But it wouldn’t be unlivable.

It’s really no wonder why my parents took the approach they did. Any parent tries to protect their kid in the only ways they know how. My parents’ approach in the early years of my gender questioning was well-intentioned, but horribly misguided, and so the results were catastrophic. I could say the exact same thing about my “gender journey” too.

Nearly every aspect of my life—from my premature birth, to my developmental delays, to my intense non-conformity, to my transition and even my detransition—threw my parents for a loop. They had kids young. They gave up career opportunities to raise what they hoped would be perfect children—brilliant children—children whose non-conformity would only show up in exceptional accomplishments. That isn’t bigotry, it’s a common mentality among immigrants from non-Western countries raising kids in the West.

Instead of getting an otherwise normal kid with exceptional qualities, in me, my parents got a kid who gave monologues about rare brain tumors at age eight and didn’t learn to tie her shoes until age fourteen. A kid who walked on her toes, wore leg braces, needed constant therapy and specialist appointments. A child with an incredibly uneven skillset. A child the world wouldn’t immediately recognize as bright, who might be too weird on the outside for others to give her the chance to prove herself.

Before puberty, my parents knew how to handle me. So did society. For the most part.

Quirkiness is tolerated—even celebrated—in prepubescent girls. But once a girl needs to wear a training bra, she’s expected to start changing everything about herself. To become palatable. Desirable. Able to someday attract a male partner worth his salt.

That’s the nearly universal expectation of parents, even if they don’t admit it. Most get their wish. Some do not. And when adolescents don’t meet that expectation, parents are faced with a choice: how to respond. The way they handle that will shape the course of their child’s entire life.

I didn’t relate much to kids my age (still don’t) but around middle school, my preference was to hang around boys. We had little prankster antics we’d use to get the attention of the girls we liked in class. The girls I liked, the girls I had crushes on paid attention to the boys I hung around. And I knew that if I were a boy, they’d probably like me back. I also thought that the sensory experience of attraction was a bunch of symptoms of some kind of disease because I struggled to make sense of what was happening in my body.

My parents knew about none of this. I genuinely did not think the context of the onset of my ‘symptoms’ was relevant.

All my parents knew was that I was begging them to take me to a doctor because WebMD told me that my ‘symptoms’ weren’t that of a crush, but rather those indicating a potential disease. I got an EKG done and an athsma test. Both came back normal. That’s what my parents knew, because the rest of the story was unfolding in my life and I was totally oblivious to what happened around me and what was going on inside me. Parents: you may think you know your kids way better than you actually know them, especially if your kid struggles to understand and express their own emotions and to make sense of the ‘noise’ going on in their body.

My parents got a daughter who preferred short, practical hair and bow ties over long curls and pretty earrings. They got a kid who hated anything itchy. Who embraced her inner professor by creating a collection of hand-made bow ties. They also got a kid who survived being born early—who they worked so hard to protect and give a future to.

My parents didn’t get a perfect kid. No parent does.

My parents got a kid who defied expectations, for better and for worse.

And they were scared.

Every part of raising me felt high-stakes, because I had obvious gifts and equally obvious deficits. My parents were afraid the world wouldn’t see what they saw. I internalized that fear. I thought my struggles were my fault. And they thought my struggles were theirs.

So when they sent me that essay, all of that—the history, the complexity, the painful beauty of our dynamic—got wiped away.

They thought they knew me better than anyone else. But by then, they were seeing me through the lens of someone else’s narrative. They were no longer seeing me.

Their panic clouded their judgment.

And instead of seeing their child as a unique human being, they began to see me as a victim of cult mind control—despite the fact that I very well might have been the first Gen Z pre-teen to declare a trans identity.

That’s why I say this clearly:

My trans identity journey was highly atypical.

So be very careful which parts of my story you relate to your own child.

Not everything will fit.

And if you push someone else’s story too hard onto your kid, you risk losing sight of theirs altogether.

The War at Home Didn’t End My War Against My Body. The War Abroad, Did.

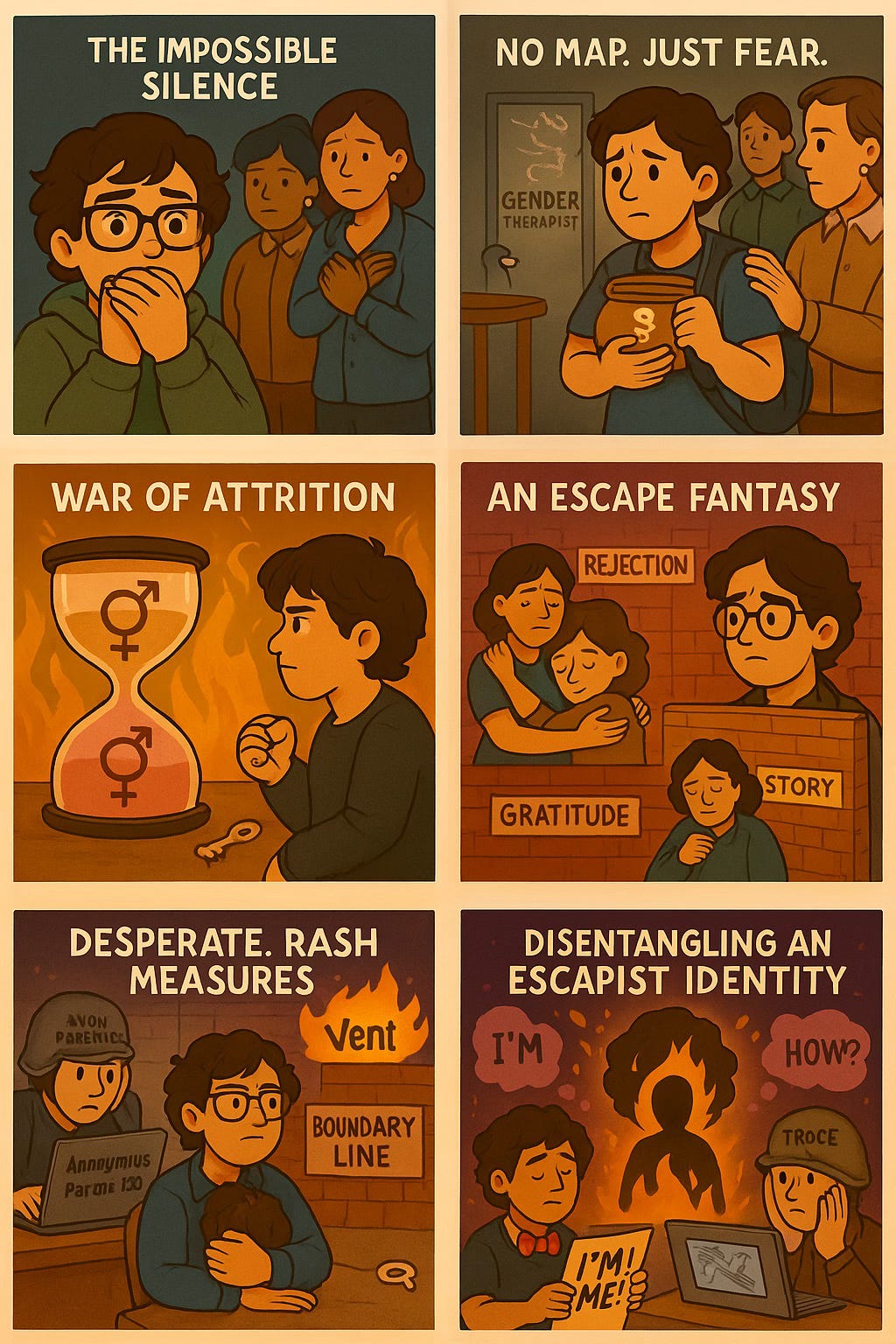

Because of the panicked way my parents reacted when I came out as trans in 2012, it quickly became clear that if I ever confided vulnerable or terrifying thoughts to them again, I would regret it. I’ve written more about this in my essay “How Trans Activists Alienated Me From My Parents,” but the gist is this: I learned that my truth wasn’t safe in their hands.

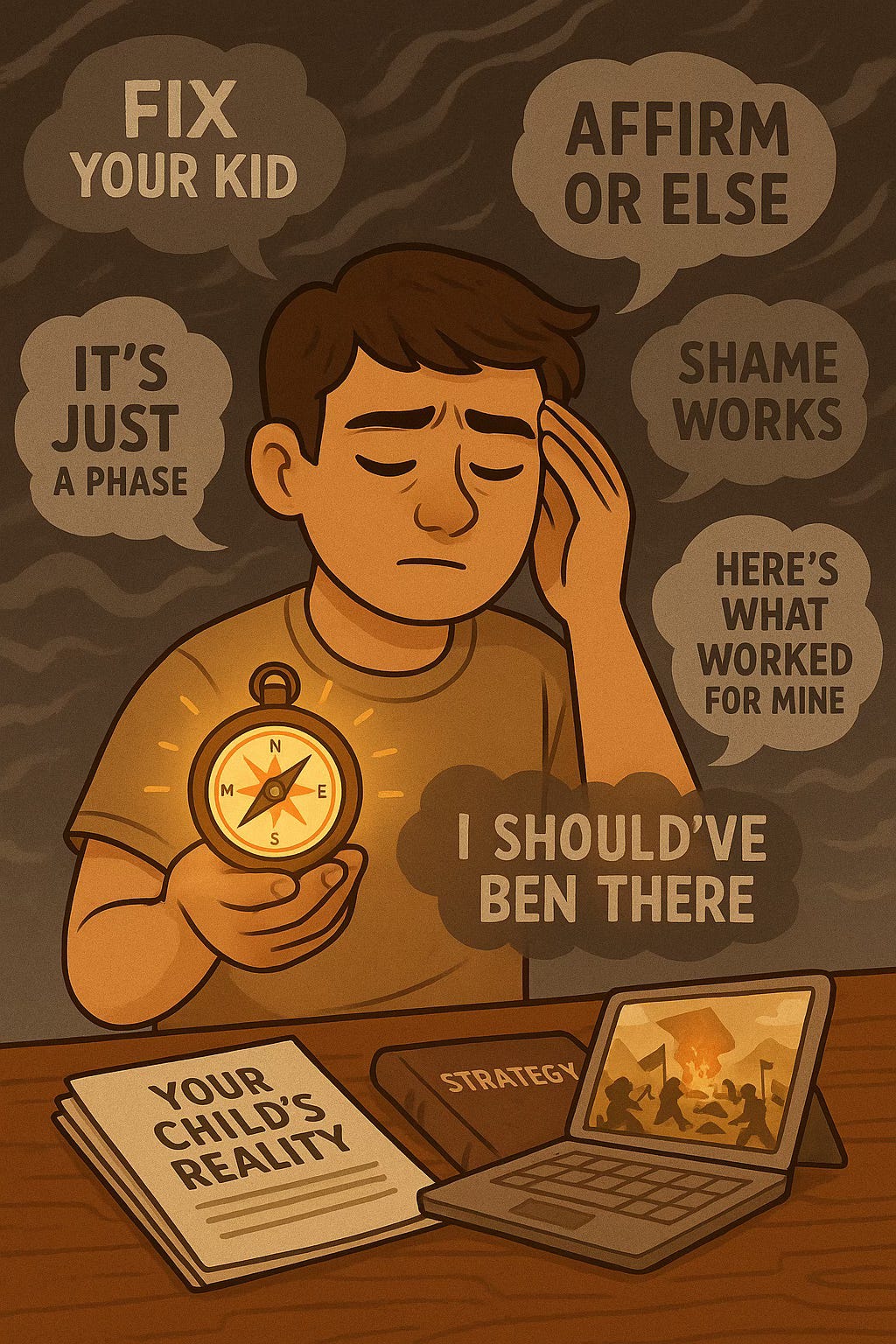

And to be fair to them—there was no information back then. I was twelve years old. There wasn’t yet an industry of gender-affirming therapy snake oil salesmen. There wasn’t a critique to be found, no community of dissenters to point to, and certainly no therapist who would help me explore why I hated being a girl. No one asked about neurodivergence. No one helped me unpack the layers. My parents had no roadmap.

And yet, they acted decisively. In fact, their strategy was far more extreme than what most parents today would dare attempt. They tied access to college funding to therapy (with a therapist of their choosing). They told me I’d need to spend time abroad in a non-Western country before they’d consider supporting any further requests. They put every obstacle they could between me and the gender clinic. And in one sense, they succeeded. I never made it into the system. But the path I took, was harrowing.

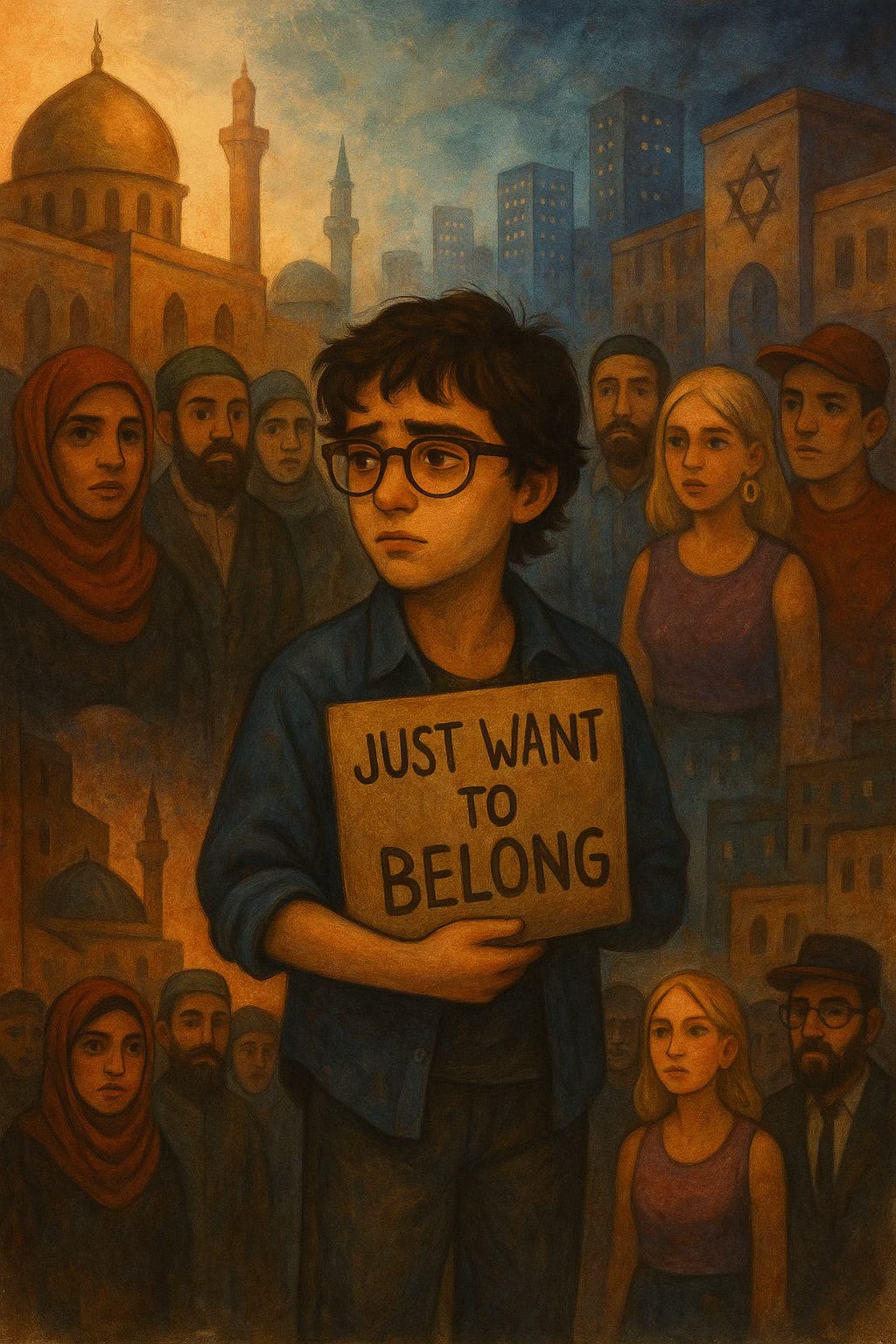

Their resistance didn’t stop me from socially transitioning. It didn’t stop me from binding my chest—permanently damaging my rib cage and breasts—because trans activists online told me, at age 12, that it was safe. It didn’t stop me from obtaining small amounts of testosterone gel from a friend. It didn’t stop me from living undercover as a man in the Middle East, where even the concepts of “butch lesbian” or “trans man” were alien. I wasn’t embedded in online trans spaces. I was searching for belonging in religious communities, in conservative and liberal circles, among Israelis and Palestinians alike—anywhere I might finally feel like I fit.

What my parents’ strategy did accomplish was making medicalization nearly impossible. They succeeded in that. They made the path so difficult that I derailed my entire life to pursue it. I lived in legal limbo for years. I learned two new languages, spoke four daily, and fought through months of bureaucracy to become a citizen of another country—all so I could access a public healthcare system far away from my non-affirming parents. Every step of the process was agonizing. And still, I fought for it, because I believed it was the only way I could survive.

Their tactics didn’t save me from incurring any transition-related injury. But my parents’ tactics did save me from incurring far greater injury. Had they retreated into panic and done nothing, I would have lost far more.

I look back now and I see the cost. But I also see the gift.

My parents’ refusal to enable medical transition—however flawed, painful, and at times emotionally disastrous—kept me out of the gender clinic. And for that, I am endlessly grateful.

They chose the only path they felt they could live with. If the price of protecting me from irreversible decisions was losing me, they were willing to pay it. My parents grieved me aloud while I was still alive—over a haircut, unshaven legs, a name I never even demanded they call me.

They drew many of the right boundaries. And at the time, I hated them for it. Not because they were wrong, I actually did see their logic in waiting until 25 (I was obsessed with the brain, after all)— but because their boundaries came wrapped in fear, grief, and emotional withdrawal.

I would’ve taken a compromise. But they were too scared to see that. I tried to invite them into my world. Instead, they micromanaged my self-expression, then withdrew entirely. The shift was whiplash. In their panic, they seemed to see me as a symbol of their failure. I got the message loud and clear: my joy caused them pain. So I backed away. Not because I didn’t love them. But because I didn’t want my happiness to hurt them. Both parties backed off because interacting with one another was too painful.

They wrote under pseudonyms. I found some of what they wrote. It wasn’t meant for my eyes. It was raw, panicked, angry. And it gutted me. Some of it made me never want to speak to them again. A note to parents: don’t underestimate how easy it is for a tech-savvy child to find what you write online. If you’re venting about your kid, make sure you’re not doing it on a shared device, shared cloud, or saved login. If your child finds your grief and interprets it as disgust or hatred of them, they will shut down. They will feel that you’ve erased them.

You certainly should not be publishing your grief of your living, trans-identified child using your real name or theirs. These “open letters” may feel cathartic to you, but if your kid finds them, you may just as well have incinerated your entire relationship. Frankly, it is a miracle that my relationship with my parents survived reading the things they wrote about me— because I was trying to be reasonable and even that was not enough to get their approval. There is nothing more viscerally shattering than being a kid whose own parents misunderstand them because they’ve superimposed someone else’s narrative onto yours, because it is too painful for them to understand you. I think I decided to make sense of myself so I could parse myself to my parents. Eventually, I came to the conclusion that both my parents and I were wrong in our perceptions of who I was.

My parents’ strategy came from love. And from fear. And it became a war.

And like all wars, it escalated. Their full-scale resistance to my identity turned what might have been a brief exploratory phase into an entrenched battle. I couldn’t walk away without losing face. We weren’t fighting over gender anymore—we were fighting for symbolic control over who I was allowed to be. Stepping back felt like surrender. And no adolescent wants to surrender when they feel like no one is listening.

Firm boundaries are necessary—especially when it comes to finances and medical decisions. But they must be paired with warmth, empathy, and a listening ear.

What I came to understand, I had to understand alone. Through years of painful, internal work.

Let me say this clearly: it is devastating to be a young person unraveling an identity you constructed to survive. When that identity finally collapses, it doesn’t feel like relief. It feels like death. Because the structure that helped you make sense of your pain is suddenly exposed as hollow. That’s not something anyone “snaps out of.” That’s an existential crisis.

Your child is in the middle of one—even if they don’t know it yet.

Trans identification, for many of us, was an escape fantasy. Not a belief system, not a philosophy, not a calculated choice. It was a way out. The logic doesn’t need to be sound. The longing is what hooks us.

And nothing—not even one war—“snapped” me out of it. I needed two.

I Thought I Was Trans—Until War Showed Me the Truth

As a 25-year-old who spent half of her life in the process of a gender transition, and who has subsequently disembarked from the trans train, I often find myself in the center of contentious debates about the "trans kid" phenomenon.

The first seeds of doubt weren’t planted by detransitioners or clinical studies sent to me by my parents. They were planted by war. In 2021, during a rocket barrage in Israel, my worldview began to crack—not because of gender, but because of politics. I started watching pro-Israel content. That changed the algorithm. Only then did gender-critical and detrans content start to show up.

There was a ten hours difference in time zones between me and my parents. Our relationship was fractured. Their panic had been deafening. I needed space. I needed silence. And I needed the sheer chaos of war to begin wondering whether lifelong medicalization was a good idea—especially for someone like me, who might not be able to reach a pharmacy during a crisis. Someone who was binding her chest while running for a bomb shelter.

Even that wasn’t enough.

It took years. I had to lose my faith in everything else first—critical race theory, social justice, the entire ideological framework I once clung to. Only then could I look at gender. Why? Because the gender identity had been mine since age 12. The others came later. The others were political. This was personal. The reason I remained so functional in the midst of my first war (or rocket barrage, as the locals think of it) in Israel, was because my relationship with my parents prepared me well.

Then came October 7, 2023. Rockets again. But this time, it wasn’t just war. It was a massacre. I couldn’t even find safety inside a bomb shelter because as rockets were fired, Hamas terrorists were rampaging through towns, throwing grenades, slaughtering civilians inside the very places we were taught to run to. People were being butchered in places they thought they were safe.

I stopped worrying about whether I “passed” as a man. I stopped thinking about gender at all. I just wanted to live.

Nothing my parents said pulled me out of my trans delusion. What did was a rock-bottom moment. For many detransitioners, it’s a botched surgery or psychiatric collapse. For me, it was watching young people my age get slaughtered at a music festival I almost attended, had my ride not fallen through. I watched it live. I had no time to grieve because in half hour intervals, a siren screamed, and I had to run again—no guaranteed safe shelter, no one to talk to. I bound my chest for years. But now I was unbinding because at first I didn’t have the time to put it on and then, just to breathe as I fled.

That was what it took.

This is not easy. And yet, people still ask me: “What’s the one thing I can say to make my kid stop?”

If that one sentence existed, you’d already know it. If one article could stop this, we’d have ended it by now. There is no magic phrase. No easy out.

This takes time. It takes strategy. It takes distress tolerance—from both you and your child. If you want to come through this with your family intact, you will need to develop that skill.

I am not an oracle. I’m 25 years old. I’m probably not much older than your kid. I don’t have certainty to offer. But I have my body of work, and the insights I earned over twelve years of believing that resembling a man was my only chance at peace.

That’s why I make my writing as accessible as possible. I use cartoons, childhood photos, clearly labeled sections. I read my essays aloud so you can hear them in my voice—not some robotic one. I do this so you, the parent, can have the roadmap mine never had.

I write not to save your child, but to help you show up for them better.

You can be the hero in your child’s story.

It may not seem like it now, but that’s not a good enough reason to stop trying. I hope my essays—and my coaching—can help you keep going.

Because your child may be lost in an identity that once saved them. And no one escapes that gently.

I’m not an expert. I’m just someone who’s been there—and who hasn’t stopped thinking about it since.

To the Parents Drowning in Information:

I also want to say this, because it matters: I know how hard this is for parents to navigate today.

Unlike my parents who were operating blind, you’re drowning in information. You are overwhelmed. You’re raising kids in a digital war zone, and then one day—out of nowhere, in the middle of your living room, while juggling your job, your mortgage, your marriage, and your other kids—one of them says, “I’m trans.” And a bomb goes off. I understand that. I do not envy your position.

You don’t have time to read every article, every medical study or listen to every podcast ever made about this topic. You probably expect yourself to and then you panic because this expectation is neither practical, nor feasible. I certainly don’t expect you to. You’re doing your best to make sense of something that feels like it appeared out of nowhere, and what you do manage to read, really grips you. It’s compelling. It makes sense in a way the world hasn’t in a while. You want your kid to read it too, because you think: “If I can see it this clearly, surely they will too.”

But they won’t. Not yet.

That’s not (just) because they’re stubborn. It’s because they’re a teenager, and they’re inside it. You are living it, but in a very different way than your child is. Because you are on the outside of your child’s trans identity mind spiral, and because you are a mature adult, you are actually capable of seeing things more clearly. Since you’re the type of intelligent adult who slaves away reading hundreds of long essays, mine included, I have faith in you. But you have to remember that your kid is living inside the trans narrative for profoundly emotional reasons, they’re not analyzing it. Analysis is unlikely to get them out unless they are actively curious about their own “gender journey.” If you are curious, your child will probably be far more likely to adopt a more curious position as well.

I don’t envy being in your position. The more people guilt or shame parents—whether affirming or not—the harder it becomes for any of us to speak honestly about the complexity of this.

There is so much pressure to find the right approach. And both sides of this debate will tell you that the other approach is not only wrong, but evil. You are blamed no matter what you do. And it’s breaking you. I see it.

Why I Write, and Who It’s For

I’m not here to blame you. I’m not here to blame your child. I’m not here to blame anyone except for the gender “experts” who I will occasionally for the sake of argument, initially give the benefit of the doubt to, purely out of the principle of charity— not because they actually deserve it.

I care about understanding behavior, even the behavior of those malignant forces in our institutions. Now that such “experts” know better and are choosing not to do better, my wrath is directed at them specifically. I’m here, writing these essays, because I do not want the hell I went through to have all been in vain. I write these long essays because I am trying to let out as much insight as I can before I get so old that I forget the intricacies of the transition path I spent my adolescence and young adulthood on. I want you to learn from it so that you can help your kid. I am writing so that my words are tools to inform your strategy, not so that they can be a substitute for your parenting.

I am processing everything that happened to me in real time. I am doing so because I want you to glean something from the nooks and crannies of my scattered brain. I may come off as blunt at times, but please know: I am not doing so because I want to be harsh. I am doing it to show empathy through logic because that is how I personally process emotions and understand the world. I think parents dealing with trans-identified kids deserve the honest truth and the extensive analysis that my perspective has to offer.

You deserve to have the honest truth presented to you, even if it is at times, uncomfortable to hear. Discomfort isn’t always a bad thing. My discomfort dealing with my own gender issues was something I chose to face head on, and my life is better for it. But, I will also say that the things I write are painful for me too. This entire experience is painful. But it doesn’t have to stay that way. You don’t have to be stuck in grief forever. Your child doesn’t have to be stuck in a damaging fantasy forever either. There is a way through. I can’t make any promises, but I do have a ton of ideas because I do happen to understand how some of your kids may operate. I was one.

I have spoken with parents in the depths of grief. And it has been my honor to help them come up with quirky, creative, out-of-the-box plans to rebuild trust and connection. This process doesn’t have to be one of misery. This doesn’t have to be war.

And for that reason, I’ll say it again:

Stop sending my essays to your child.

Unless they’re begging to see them, let them come to it in their own time. Use my writing for you. That is who it is meant for. Let my writing ground you. Let it clarify things. Let it guide your strategy, not fuel your panic. Let my writing help you to reframe your thinking about how to navigate these difficult situations with logic, reason and insider tidbits from the half of my life I spent on the “inside.”

I don’t want any more parent martyrs. I don’t want any more child martyrs. I don’t want anyone else to be sacrificed on the altar of the trans religion—or the increasingly dogmatic fringes of gender-critical belief, either. I’m not interested in purity tests. I’m interested in peace. I am interested in practical solutions. I am interested in making them as fun and interesting as possible for you, because you and your kids deserve some levity in this process— rather than tension bubbling below the surface because no one wants to talk about anything hard, or because you are trying to bombard your kids with scary stories in the hope of waking them up. There are objectively better strategies than those most commonly used ones. Let me help you find them.

Don’t Blindly Accept My Opinions, Or Anyone Else’s. Think For Yourself.

I understand why you want to send my essays—or any detransitioner’s essays—to your child. I understand why you want to bombard them with scary stories or studies. I understand that you are desperate to figure out what’s going on in your kid’s mind. And that impulse, in and of itself, is commendable. But these tactics won’t bring the results you’re hoping for. And you cannot superimpose my story onto your child’s, no matter how much resonance you think you’ve found. I am not your child. Your child is a unique individual.

In fact, your child is trying to get you to see exactly that. That they are someone distinct, someone who cannot be reduced to your expectations. That’s why they’re identifying as a fundamentally different kind of person than the one you believe them to be. It’s not really about ideology at first. Most of us didn’t get pulled in because of the logics of the ideology—we got pulled in because of the promise. The promise of happiness, of wholeness, of becoming our “authentic selves.” The ideology came after, as a way to rationalize why that promise had to come true.

So when your kid says they’re trans, what they are often doing is engaging in a messy, misguided, but developmentally normal attempt to individuate. Rather than affirming the false conclusions they’ve drawn, or fully enabling a financially dependent teen to jeopardize their health and future in the name of “keeping the peace”—and rather than turning your panic into debate or weaponizing my story as a “gotcha”—you should meet them with something else: acknowledgment, reasonable boundaries and strategy.

Show them that you see the longing to become their own person. Then, calmly and compassionately, put down boundaries. Stop debating the facts every day and start asking better questions: Why is this identity so tantalizing? What need is it meeting? What may be going on beneath the surface? How can those needs be met in a way that doesn’t involve irreversible harm?

If you can figure that out, and find grounded, reality-based ways of helping your child pursue the feeling they’re chasing—belonging, purpose, autonomy—without transition itself, your limited time and relational capital will go so much further. And once you’ve done that work, move on. Bond over something that isn’t gender. That’s where connection starts.

All of this is exactly the kind of thing I help parents navigate in coaching.

The difference between 2012 and now is that not only do you have voices like mine, you also have an overabundance of voices—some helpful, some harmful. My parents had no information. You have too much. You are simultaneously drowning in information and being burned alive by everyone’s hot takes. And you do not have time to vet them all.

Some of these voices will give you genuinely good advice. But many are loud culture warriors with strong political agendas and little credibility. Many offer you simple, seductive solutions—often involving shame, mockery, rage, or despair. Avoid them. Don’t listen to anyone selling you a magic cure. Don’t listen to anyone telling you your kid is a lost cause. Don’t keep following advice that has already failed you ten, twenty, a hundred times. Don’t let anyone convince you to stay stuck in grief, or to quit trying to reconnect with your kid.

I will not lie to you: no matter how you handle this, the situation will be hard. There is no script I can give you to solve all of your problems. But there are patterns. There are strategies. And there are insights, many of which I’ve tried to offer through the lens of my own experience.

This is where I can be most useful to you—not as a therapist, not as a guru, but as someone who has lived it, someone who thinks in systems and patterns and logic. I can help you decode your kid’s behavior based on those skills and through this framework specifically. I can explain how certain forms of neurodivergence show up in high-functioning young people, in girls in particular, who fly under the radar. I can give you my two cents based on my own experiences in my own brain with the hope that your child’s brain may operate in a similar enough way to mine that you will be able to better understand their process. I can help you create a plan. But I am not your savior, and my essays are not a substitute for your actions.

I don’t write slogans. I don’t offer hot takes. I spend hundreds of hours writing long, dense, detailed essays because I believe that you deserve real analysis. Not emotional bait. Not guilt trips. Not platitudes. I believe you deserve real tools.

And most importantly: you deserve choice. You deserve to think critically about every piece of advice you receive—including mine.

Let my work be one piece of a wider framework you’re building, not the entire framework itself.

Trans Identity: When Parents Try to Win the Debate, Their Kids Alienate.

Note: The "play” button at the top is not a decoration. It is an audio-taped version of myself reading this essay.

A Note on My Perspective, and How I Can Help:

Instead of sending your trans-identified kid my essays in the hope that my essays will impact them in the same way as they impact you— here are some things— not that you must do, but that you should consider trying:

Invest in your own sanity. Your child needs you to be their rock, not to be on the receiving end of their parents’ panic. I recommend getting a weighted blanket. All of my initial critical thinking about gender happened under a weighted blanket, which regulated my nervous system and allowed me to tap into my logical brain rather than being subsumed by primitive emotional responses which impeded my reasoning skills. It’s great for some people with sleep issues, anxiety (which you are undoubtedly feeling), it’s great for many people with ADHD and Autism as well. I’ll probably write more about this in an essay because my weighted blanket actually changed my life. Who knows— it might change yours as well. Just do your research about which weight to get. If you’re lucky (or just neurodivergent) it might help you more than you could ever realize, in making strategic decisions rather than purely emotional ones. All of my essays are written under a weighted blanket.

Get yourself a detective hat. I’m not joking here. If your kid is trying to develop their personality and sense of self by wearing a costume, why not consider doing the same? I’m not saying you have to wear the thing all the time, but it may be helpful for you in thinking this through if you can do so with levity, and while trying to embody a role you wish to assume. Remember, now that you’ve read this essay— you understand the importance of not trying to debate your kid out of this, you are trying to become a detective. In the process, you may get a whole new level of insight about what your kid is trying to do with this gender stuff.

Read my essays, take notes (if you’re a nerd and that’s your style) & reach out via DM to book a parent coaching session. If you’ve made it this far—and especially if you’ve read more than one of my essays—you’re not a surface-level parent. You’re trying to get to the bottom of this. You’re thinking critically. You won’t settle for easy answers when truth and your child’s future is at stake. You want to understand your child without losing your own grip on reality. You want to be steady without being cruel, compassionate without caving in, and wise without being manipulated.

That’s why I offer coaching, based not on therapeutic credentials or any kind of formal expertise— but based on my own analytical skills, my 12 years of trans identification, my lived experience, my pattern recognition and my absolute disgust at the lackluster advice being given to parents by idiotic culture warriors without even so much as two brain cells capable of uniting to create a semi-insightful, applicable or half-compassionate thought.

My firm belief is that when gender exploration is in its early stages, it is relatively easy (with the right guidance and information) to craft a strategy which is truly exploratory—where social and medical transition are both off the table due to clear, loving boundaries placed by parents—without fundamentally sacrificing the child’s health or the family relationship. That doesn’t mean the situation will resolve easily—likely, you could be in this for several years because of how thoroughly this ideology has permeated our institutions. But addressing this early and thoughtfully—not through panic and escalation, nor panic and avoidance—reduces the chances that this identity will harden into a crisis that uproots the entire family.

However, if your child has already been affirmed, socially or medically transitioned, or if they’re financially independent and asserting this identity as an adult, the situation becomes much more complex. In some cases, you may be facing an uphill battle, forced to choose between maintaining a carefree relationship or protecting your child’s long-term well-being. In these cases, every decision—including doing nothing—has consequences. There is no easy out. But that doesn’t mean it’s hopeless.

Even estranged families can find their way back to one another. My parents and I did. They rescued me from a war zone. That was the start of our repair.

If you’ve found value in my writing, coaching is the next layer. It’s where we get specific. We stop talking about kids like yours and start talking about your kid. I cannot give you therapy or some perfect solution guaranteed to work, but I can give you my analysis, my lived experience, my insights and my quirky little ideas. Together, we can tailor my insights about the nature of this identity exploration to your insights about your specific family and your specific child. Together, we can make the difficult process of reconnection and exploration something which you don’t have to do alone—and frankly, you shouldn’t.

Let me help you think this through. I would be honored to help however I can.

And in my coaching sessions, I’ve helped parents come up with other kinds of reconnection plans—quirky, unusual, creative approaches that don’t rely on control or guilt, but on strategy, timing, and trust. I’ll probably write more about at some point. But, since I’ve already promised you a series about autism in girls, I will now get to working on that. We’re all learning together.

Below is a kind note from

whom I was lucky to work with. Check out her blog for a spiritual and savvy approach to pressing moral issues of our time. As I’ve said many times, the parents I’ve encountered through this time of life, and whom I have worked with are some of the coolest people I’ve ever met. I have yet to be proven wrong.You can DM me here to book a parent coaching session:

In any case, stay tuned for my upcoming series about autism in girls. I wanted to publish it today, but so many parents have DMed me about sending my essays to their kids that I had to write this essay first. I hope you have a good week.

Did You Enjoy this Essay? Does my work teach you things?

If so, please become a paid subscriber to support my work, so I can continue bringing my insights to you. My essays take a lot of time and effort to produce and to bring to you. As a 25 year old independent writer, your $8 a month is very much appreciated.

Maia’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber by clicking on any of the buttons in the post.

Do you have a kid navigating gender confusion and trans identification?

If so, I offer parent coaching sessions to help you figure out how to best navigate your specific child’s situation, in a compassionate and practical way. If this is of interest, please DM me.

"Trans identification, for many of us, was an escape fantasy. Not a belief system, not a philosophy, not a calculated choice. It was a way out. The logic doesn’t need to be sound. The longing is what hooks us." This really spoke to me about our daughter. Thank you Maia for your contributions to the caring parents trying to work through this.

I appreciate your perspective, Maia. As a therapist I'm still just taking everything in about gender identity, aware of the complexity and that we are all in the middle of an unfolding movement that can't be easily grasped from the inside. But as an adult neurodiverse woman, I often find myself so grateful that I was born when I was (about 10 years earlier than you). I think I would almost certainly, given my inability to perform a particular kind of womanhood, have really struggled to get to where I am today otherwise: someone who enjoys being a woman, and finds the idea of being gatekept from femininity because of my lack of "girliness" utterly strange, barely worth noting. The longing to fit in when you are "different", the grasping of a potential solution, is so poignant.