"Trans Kid" Jazz Jennings Was a Victim of "Good Parenting"

EXCLUSIVE: Where Was Everyone When Jazz Jennings Got Castrated (Part 2)

(Note: The “play button” up top isn’t there for decoration. Click on it to hear me reading my essay so you can listen to it as a podcast)

The early 2000s marked a profound shift in Western parenting culture—one that coincided almost eerily with the rise of pediatric gender medicine. As parents became more anxious, more deferential to “experts,” and more invested in their children’s emotional well-being, a new ideal emerged: the emotionally intelligent, self-actualized child whose inner world must be protected and affirmed at all costs.

Childhood, once seen as a rough-and-tumble stage of unpredictable growth, was recast as something fragile and clinical—a series of milestones to be optimized and symptoms to be monitored. In this new framework, a child’s emotional distress was rarely viewed as a normal, passing phase. It became a red flag. And into this landscape of hyper-attentive parenting and widespread medicalization of youth entered the concept of pediatric gender transition—not as a fringe phenomenon, but as the logical endpoint of a culture that had already begun diagnosing childhood itself.

Jazz was a victim of the very ethos of “good parenting” by the standards of 2000’s parenting. In this second part of a now three part essay (yes, I know— it was only supposed to be two parts) I will discuss the ways in which, rather than Jazz being a victim of two parents who were hell-bent on stunting his development for profit (as goes the narrative on the right)— he was actually a victim of a prevalent mindset which gripped an entire culture of parents.

Many parents who consider themselves to be excellent parents are probably making many of the same types of potentially misguided decisions that Jazz’s parents made- without even realizing that this is what they’re doing. This includes those parents who agree with the way the Jennings’s handled their son’s situation, and including those who would never think to handle Jazz’s early gender non-conformity and distress in the way Jazz’s parents did. As such, I’ve decided to expand this essay into a three part essay.

This is Part Two of a Three Part Essay. The first part is “Trans Kids Aren’t Born. They’re Created.

Trans Kids Aren't Born. They're Created.

When I began to find myself swimming in a sea of trans content at the age of 12 in 2012, one of the first stories of "trans kids" I saw was the story of Jazz Jennings. I watched grainy, low-quality footage from his 2007 special. Even though Jazz is only one year younger than me, I thought he was much younger—because I was seeing him at six years old whe…

When the Rise of ‘Parenting Culture’ Met Pediatric Transition

The rise of pediatric transition coincided—almost too perfectly—with a radical transformation in Western parenting norms. It wasn’t just that puberty blockers became available for off label use as a treatment for pediatric gender dysphoria; it was that they became available at a time when many parents had begun outsourcing their instincts to “experts” and treating childhood self-expression as sacred— even inviolable.

In previous generations, small children were rarely taken seriously. They were expected to adapt to their environments, not the other way around. But by the early 2000s, middle-class parenting had undergone a profound shift. Families were smaller, and children had become the precious centerpieces of domestic life. Instead of relying on intuition, tradition, or extended family, parents turned to a booming industry of parenting books, developmental psychologists, and internet advice columns. In the name of raising “emotionally intelligent,” high-achieving kids, they devoured expert guidance in the form of the growing ‘parenting book’ industry, and fretted constantly about damaging their children’s fragile self-esteem.

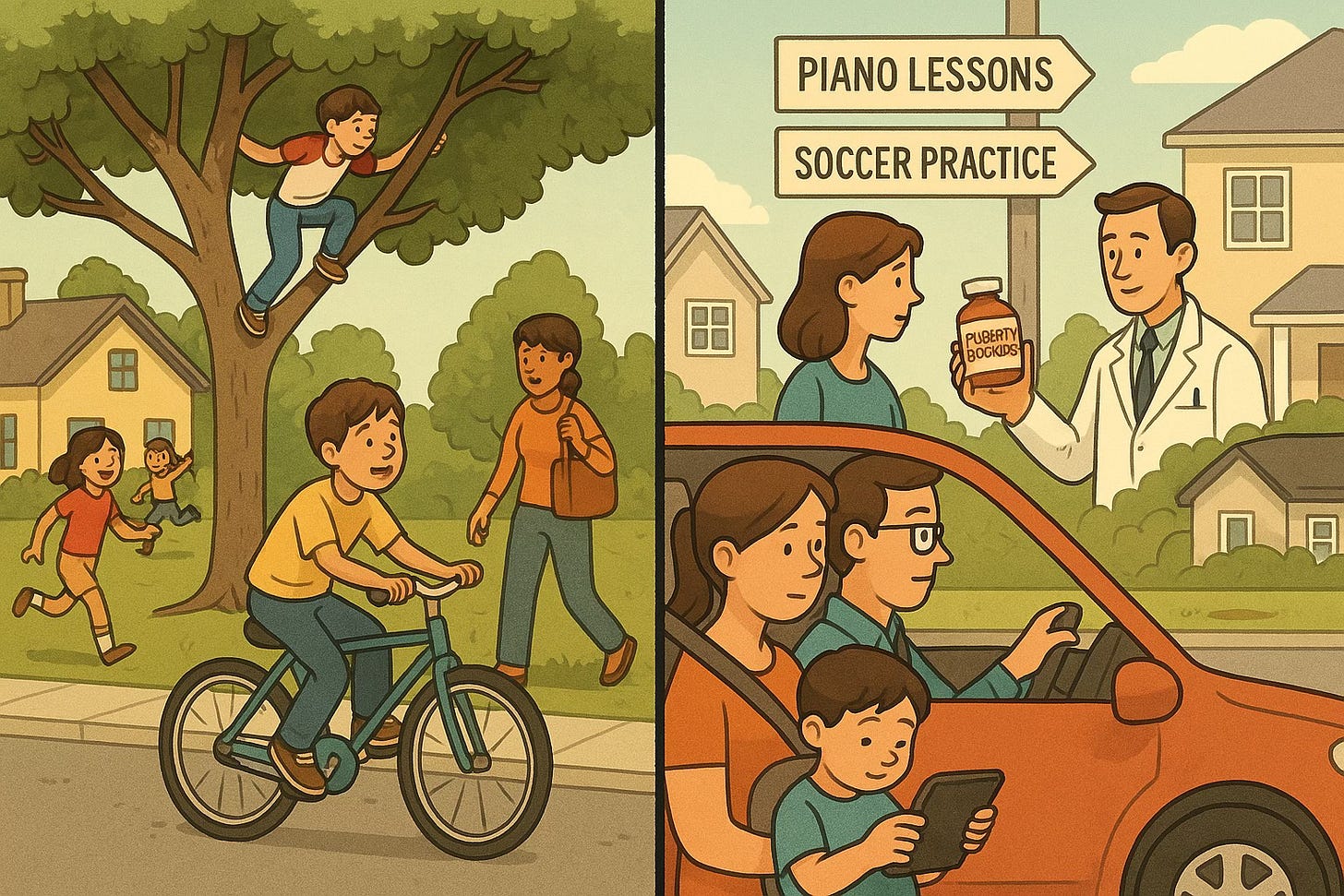

At the same time, children’s autonomy was restricted in new ways. Free play and neighborhood independence—hallmarks of earlier childhoods—were replaced by an endless carousel of adult-supervised extracurricular activities. Kids were enrolled in enrichment programs, language classes, and sports leagues before they could even read a chapter book. And when they weren’t being shuttled from one activity to the next, they were often pacified by television or, increasingly, the internet. This highly structured, overstimulated environment left little time for kids to just be kids: to get bored, invent games, navigate conflict with peers, or develop self-understanding through unmediated experience.

Ironically, in trying to raise well-rounded, emotionally attuned children, this cultural shift made parents hypersensitive to every sign of distress. Rather than helping kids build tolerance for discomfort and ambiguity—a necessary part of growing up—parents became fixated on alleviating distress at all costs. Emotional suffering was reinterpreted not as a normal developmental challenge to grow through, but as a crisis requiring immediate intervention. This created fertile ground for identity-based explanations for children’s struggles. If a child expressed confusion or unhappiness, there had to be a name for it—and a solution.

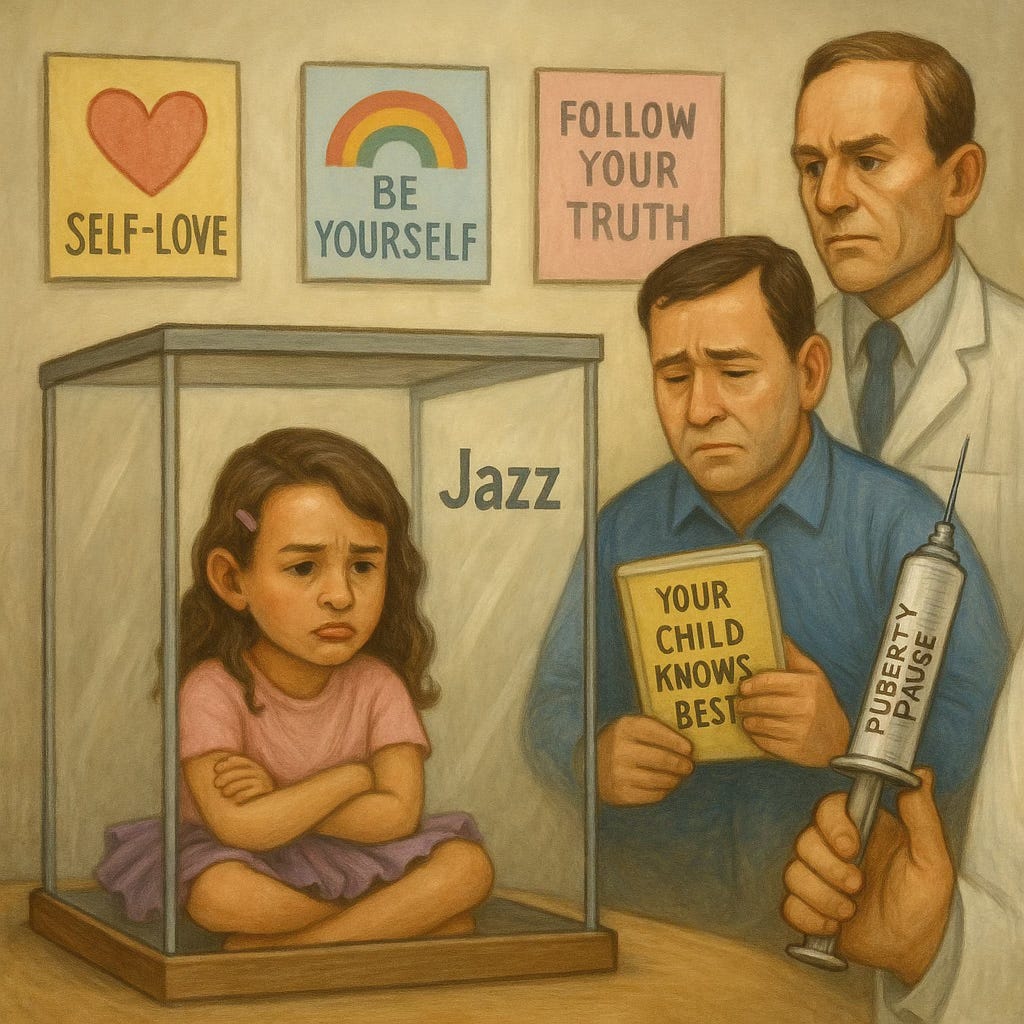

So when a little boy said, “I’m a girl,” many parents—armed with advice from books and TV talk shows warning against invalidating a child’s inner truth—were too afraid to correct him. They worried that doing so might scar him for life or crush his budding sense of self. These were not neglectful parents. They were loving, anxious, hyper-involved parents trying desperately not to fail their kids. But in their effort to avoid harm, they often mistook normal developmental behaviors—like dressing up or rejecting rigid gender roles—for signs of a deep, immutable identity. And they trusted their small children—children with no life experience—to somehow know enough about their future desires to tell them if and when it was time to reverse course. That is an insane amount of decision-making to place on a child who’s still learning to potty train, or to tie his shoes.

Parents think that by following their child’s lead, they’re offering a wide array of options to aid self-discovery. But what they forget is that having too many choices paralyzes small children.

And now, for the first time, doctors had something to offer: puberty blockers. Though intended to pause puberty after it had already begun, their very existence gave clinicians license to support social transition even earlier.

The logic went: “Why not let the child live as their ‘authentic self’ now, so that by the time puberty arrives, they’ll know who they are and avoid the distress of developing in the ‘wrong’ body?” This, despite the fact that early social transition was never part of the original Dutch Protocol, which explicitly cautioned against tampering with identity development in young children. The Dutch clinicians—flawed as their model may have been—at least acknowledged that many children with gender confusion would grow out of it. In the U.S., that nuance was drowned out by a cultural obsession with immediacy, affirmation, and emotional validation.

Then, Came Jazz Jennings.

Then came Jazz Jennings—introduced to the world by Barbara Walters, embraced by Oprah, and ultimately elevated to reality TV stardom. Jazz’s story seemed to confirm what many parents already feared: that an extremely gender-nonconforming child is doomed to suffer. Jazz’s story also offered a new explanation for why these kids exist: that these kids might not just be a tomboy or an effeminate boy, but a girl (or boy) trapped in the wrong body. Jazz’s story wasn’t just broadcast—it was packaged as a roadmap. And parents, already primed by changes in parenting culture, to treat their children’s words as sacred truths, began to see Jazz in their own sons and daughters.

Right as our society could have, perhaps via the gay rights movement, begun to finally accept extreme gender non-conformity both in girls and in boys— the idea that boys could love dresses or dolls while still being boys evaporated. The possibility that a “tomboy” might grow up to be a confident girl, maybe a lesbian, was no longer offered. Gender nonconformity was no longer a personality trait. It became a diagnostic warning sign. And when the experts echoed this model, parents believed they had no choice. After all, they were being told that not affirming a cross-sex identity could lead to suicide, including in a toddler who was not suicidal.

And so, the availability of puberty blockers—which normalized the practices of early social transition—ushered in an entirely new model of childhood gender non-conformity. Children no longer grew into themselves. They declared themselves, and adults followed. “Children should be seen and not heard” became “children are the experts of their own identities.” And any parent who dared to push back risked being labeled a bigot, ignorant, or even abusive.

This was passed off as social progress. In reality, it was the wholesale abandonment of the hard-earned wisdom of earlier generations—replaced by a fragile ideology built on denial, fear, and magical thinking. And it paved the way for thousands of children to embark on irreversible medical paths before they were old enough to understand what any of it meant.

Pediatric Gender Medicine Didn’t Emerge in a Vacuum—It Rose Alongside the Mass Medicalization of Gen Z Childhood

Gen X parents of Gen Z kids sought child-rearing advice from parenting books, probably because some aspect of their own childhoods failed to meet their needs— and so they totally overcorrected. I was the odd nine year old who became obsessed with reading parenting books as a way to understand kids my own age, after I found stacks of them in the basement of my childhood home. I read book after book, which detailed strict timelines about developmental milestones which, if children didn’t reach within specific timeframes, warranted a visit to one expert or another. I was introduced to a multitude of neurological issues, psychiatric diagnoses and developmental problems in these parenting books, and subsequently became thoroughly obsessed with researching them myself.

While it is good to keep an eye out for developmental delays which require early intervention, the truth is that child development can be very non-linear without any underlying pathology. If middle class Gen X parents had raised their kids in multigenerational family structures, rather than in isolated suburbs— this wisdom would have been much more easily passed down from their own parents: that kids learn best through unstructured, unsupervised play with their peers.

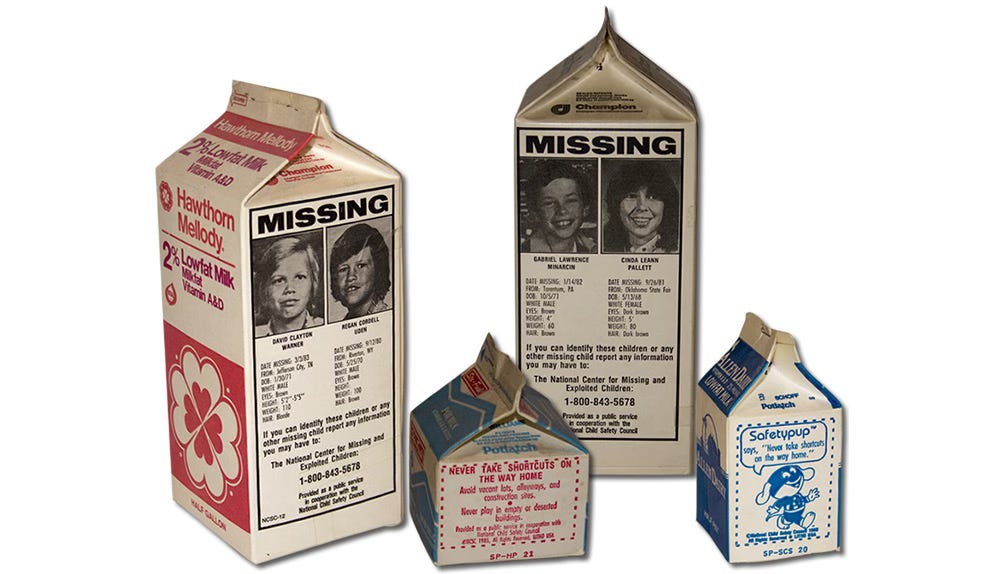

Gen X parents, who were raised on horrific stories of missing children plastered on milk cartons, had collectively decided that the types of unsupervised play they had grown up on, were far too dangerous for their own kids to engage in. In most cases, fretting over a child’s development and safety did far more damage to Gen Z— whose lack of unstructured play manifested in an array of social and emotional deficits, which parents increasingly sought expert advice to ‘treat.’

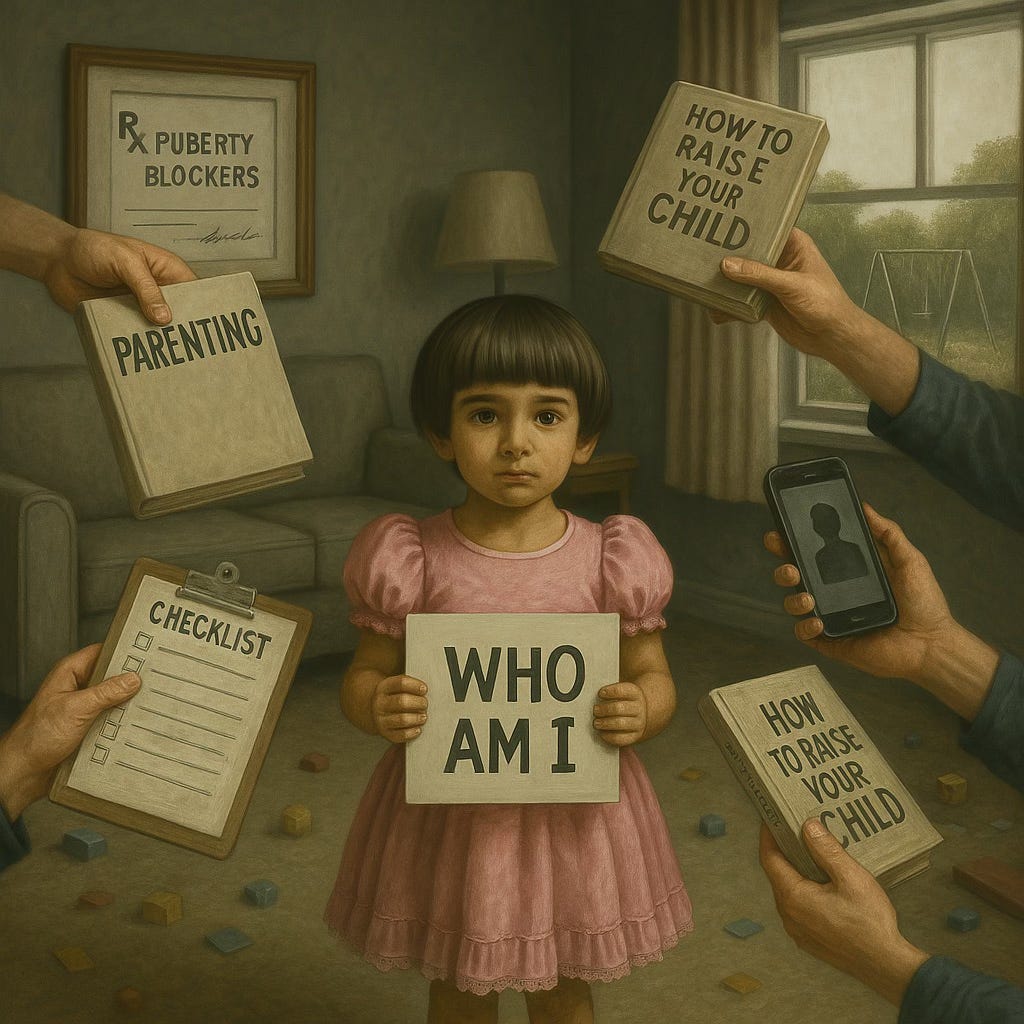

Here’s the thing: if you bring your child’s problems to your own parents, they may reveal that as a child you behaved the same way and emerged just fine. If you take your child’s problem to a doctor because you discount the validity of your own parents’ wisdom (because of the mistakes they made) and if you have been made to feel that in the absence of a master’s degree in child development, that you’re incapable of parenting your own kids— the doctor, whose job it is to provide you with a diagnosis and an intervention— will just do their job. They don’t live in your house, they don’t know your child, they don’t see the family dynamics— they merely see the results. Instead of recommending changes to the environment, as doctors, they will always recommend intervention.

The rise of pediatric gender medicine didn’t come out of nowhere. It emerged within a broader cultural shift in how we understood childhood itself: not as a stage of messy, nonlinear development, but as a medical condition to be managed. Gen Z was the first generation raised with a diagnostic manual in one hand and a prescription pad in the other. By the time they entered kindergarten, millions were already being screened for psychiatric “disorders”—attention deficits, mood dysregulation, sensory sensitivities, learning delays. Children who once would have been described as shy, spirited, difficult, quirky, imaginative, or just late bloomers were now placed into ever-narrowing diagnostic boxes. And once a label was applied, it often followed them for life.

This wasn’t entirely new—medicalization of childhood had been gaining steam since the 1990s—victimizing young millennials. But the trend exploded with Gen Z. Rates of ADHD diagnoses soared, and stimulant prescriptions were handed out like candy. Anxiety and depression became the default explanations for adolescent discomfort. Children were medicated not to manage severe pathology, but to help them perform better in school, sleep through the night, or simply “cope” with normal developmental stressors. Pathology replaced personality. Traits that once made a child unique were now symptoms to be treated.

It was in this climate—where nearly every form of youthful struggle was reinterpreted through a clinical lens—that developmentally typical gender distress or confusion faced by some subsection of kids was rebranded as “gender identity disorder” and then, as “gender dysphoria.” And because the broader culture had already begun to accept that children’s identity claims and behaviors should be managed through professional intervention, there was little resistance when the newest wave of experts insisted that a child’s declaration of being “born in the wrong body” was not only valid, but required urgent medical affirmation.

In truth, pediatric gender medicine was the logical next step in a system that had already normalized giving six-year-olds amphetamines and eleven-year-olds SSRIs. Once we accepted the idea that any deviation from a perceived norm—emotional, cognitive, or behavioral—required a diagnosis and a treatment plan, it became easy to believe that a girl who hated her body wasn’t just insecure but was actually a boy. That a boy who pretended he had long hair by draping a towel over his head, wasn’t just playful— or that the boy who feared puberty wasn’t just anxious but, that they were inherently female. What began as psychiatric overreach metastasized into an onslaught of somatic intervention.

Medicalizing childhood created a culture where growing pains became red flags. And in this context, puberty itself—the most natural, if awkward, stage of development—was recast as a medical emergency for youth who expressed their distress by using the language of gender identity. The fact that puberty is a temporary state, one that naturally resolves or recalibrates many of the discomforts teens experience, was forgotten. What mattered now was intervening early, affirming quickly, and pausing development—even if no one could say for sure what the long-term consequences would be.

Pediatric gender medicine fit seamlessly into this new therapeutic paradigm. It offered a “solution” to emotional suffering that bypassed deeper psychological inquiry. It offered a diagnosis. A treatment. A path. It gave parents something to do and children something to identify with. In a culture already primed to treat emotional distress with pills, procedures, and labels that stick for life, it was no surprise that “gender-affirming care” wasn’t met with a wave of skepticism—but with widespread applause.

Conclusion:

Pediatric gender medicine did not arise in a vacuum. It was born of a culture that redefined parenting as risk management, childhood as pathology, and identity as something to be validated, not explored. In trying to protect children from discomfort, many parents inadvertently exposed them to far greater harms—outsourcing judgment to experts, reinterpreting ordinary developmental turmoil as diagnosable conditions, and allowing fragile identity claims to guide irreversible decisions.

What began as a desire to honor children’s emotions devolved into a system where growing pains were feared, and where the most intimate aspects of identity were medicalized before they had the chance to mature. If we are to understand how pediatric transition took hold so rapidly and with so little resistance, we must confront not only the failures of the medical establishment—but the well-intentioned anxieties of a generation of parents who thought they were doing everything right.

As such, it is misguided to stick all of the blame on Jazz’s parents. After all, they were literally just taking the advice that the “experts” gave them. They were unquestioningly doing exactly what American culture of that time told them to do, and they did it earlier than other American parents would.

American culture has a really big critical thinking deficit because of its desire to constantly innovate. It sees innovation as necessarily better than sticking with the old and well-known, tried and tested ways of doing things. While innovation doesn’t have to be a bad thing, especially in the realm of technology and even medicine— children aren’t evolving machines.

Children are small, inexperienced human beings who are very much molded by their environments. American culture’s constant drive to make everything newer and better can be very destructive when it comes to child-rearing. Parenting is hard enough, without every generation of parents being expected to become child rearing experts by mastering an entirely new ethos. In this case, the ethos of child-centered parenting became the well-intentioned catastrophe that in and of itself, induced many of the developmental delays I see in my generation— no puberty blockers required.

The narrative that the tragedy of what befell Jazz was the tragedy of having particularly evil, abusive or neglectful parents is not only overly simplistic, but wholly inaccurate, in my opinion. A much less emotionally-charged, self-reflective and reality based narrative is in order. Jazz was the ultimate victim of the so-called “good parenting” ethos of the 2000’s onward, which prioritized child-centered parenting and constant intervention. When you combine this ethos with the nature of American for-profit healthcare, it caused an entire generation of good parents to do really destructive things to their children. Jazz’s parents were so involved and so neurotic, that they were very easily convinced that the “experts” could help their child with a new idea and a new treatment protocol, to the exclusion of their own common sense. Any parent could easily make that mistake, and many already have: not just in regards to consenting to pediatric gender medicine on behalf of their minor child, but in every other medicalized (and non-medicalized) realm of parents bubble-wrapping their kids from a world they have considered to be dangerous.

What in the world, after all, is more American than that?

Have you enjoyed this article?

If so, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work so I can continue bringing my insights to you. Your $8 a month greatly helps me to continue bringing this content to you, and I am exceedingly appreciative of it.

If you are a free subscriber, you should be able to upgrade by clicking on any of the subscription buttons in this post and by clicking on “manage subscription.”

Do you have a gender questioning young person you’re trying to help navigate through their gender questioning?

If so, I offer parent consultations/coaching sessions to help you come up with a good strategy to best support your specific kid through this process. If this is of interest, please DM me.

Part Three is out Now:

How Everyone Failed Jazz Jennings

Before we begin, note that the play button up top isn’t a decoration. It’s an audio recording of me reading my essay for your convenience. Click on it to listen like a podcast.

Thank you fro the very interesting analysis of American Parenting ( anno 2000).

Sadly some of this philosophy has crossed the North Atlantic to wash up on our shores. ( An influence which Hubby and I tried to ignore.) Now I finally (&truly) understand why we were always at odds with the parents who implemented Modern Parenting Ethos and the schools with the Latest Pedagogic theories. I look forward to reading part 3.

Your exploration of this topic shows wisdom and compassion.