Less than a week after graduating from high school, I celebrated my 18th birthday at an indoor trampoline park with a few of my closest friends. We spent the afternoon climbing ninja courses, doing front flips into foam pits, and throwing foam balls at one another- jumping as high as we could, attempting to experience a fleeting millisecond of defying the force of gravity. Between the head rushes, the greasy pizza, the soda pop, the laughter, and the several narrowly avoided instances of my eyeglasses almost snapping in half, that day was nothing short of euphoric.

My 18th birthday party was my farewell to my childhood, the last six years of which had been marked by a gender identity struggle that became the source of an all-consuming, palpable tension, simmering just below boiling point and requiring the entire family’s effort to prevent it from spilling over and scalding us all. This ‘farewell’ to my childhood also contained within it my desperate attempt to hold onto my youthful innocence for just a little bit longer. I wished to recover some of the childhood levity that disappeared the moment I was exposed to the idea that becoming a man could solve my adolescent misery. From that point forward, I became singularly fixated on transition as the answer to all my problems.

Following my 18th birthday, I had a few more months before I was going to begin my university studies and could finally begin the process of a gender transition — a future I had carefully planned since the age of 12. Transition was the only aspect of my future I had even thought to plan, and the importance of every other decision seemed to pale in comparison. I chose my university solely based on how close it would be to my aging childhood cat, Valentine. I didn’t have a clue about what I wanted to study or what I would be interested in pursuing professionally.

I just knew that I needed to study somewhere so that I could finally leave my parents’ house and begin the gender transition I had spent years secretly planning. Now was the time to get my ducks in a row so I could enter college and introduce myself under my new identity.

As a young teenager, I had experimented with multiple methods of flattening my breasts as discreetly as possible, guided by online instructions found on FTM trans forums. Convinced I could stunt their natural growth by binding them young — and therefore qualify for a less invasive ‘top surgery’ that wouldn’t leave me with two noticeable scars across my chest — I became committed to perfecting the ‘art’ of breast binding in secret.

I learned that I could fashion a binder using a variety of items that could be purchased at a pharmacy, a medical ‘posture correction garment’ prescribed by a chiropractor who didn’t question why I would want an already tight garment in an even smaller size, and multiple sports bras worn at the same time but in various different directions. I was physically miserable and existed in a state of ever-present paranoia about ‘getting caught’ — but I was also focused on doing everything in my power to prepare myself for the lifelong road I had staked my entire future on since before I had even become a teenager.

Right before a summer family trip to Europe, I squirreled together a VISA gift card and some of my birthday money to buy my first ‘official’ breast binder, which I had shipped to my friend’s house. As my family drove through the mountains of Italy, remarking on the incredible view of chaotic motorcyclists nearly edging each other off of a cliff as a mechanism to stave off their impending motion sickness, I checked on the shipping status of my breast binder. As I floated off the coast of Capri, giving myself my fourth-ever sunburn, I ran through a list of possible new masculine names I would call myself.

The day after I returned from that vacation, still jet lagged, I went to my friend’s house to pick up the breast binder I had wanted so badly for so many years. I went to the bathroom to try it on. I ripped open that package with reckless abandon, like a kid on Christmas morning. But this time, there were no eyes eagerly fixed on me, awaiting my reaction. This time, I was about to open the first gift I had ever bought for myself. This time, the only reaction that mattered was my own. Around that time, trans communities had begun to use the phrase “gender euphoria,” which they defined as the opposite of gender dysphoria — a radical alignment between the body and the mind. I thought that surely, that day would be my first experience of it.

I removed my glasses and, shoulder by shoulder, squeezed the binder over my upper body. That first time putting it on required an entire acrobatics act to weasel my way into the thing. Under the irritating flicker of three fluorescent lightbulbs mounted to the ceiling, I put my glasses back on and stared at my reflection in the mirror for the first time in years. But instead of the euphoria I had expected to feel, I was met with the all-too-familiar crushing dysphoria I was convinced would be mitigated by ‘properly’ binding my breasts. Staring at myself in the mirror, I saw a girl in an odd-looking cloth morph between a sports bra and a crop top, staring back at me. I became even more aware of the width of my hips, the narrowness of my shoulders, and the presence of my flattened breasts. I wanted to cry.

Gender Euphoria, or Sensory Relief?

But then I remembered that the binder is just an undergarment, so I put on my shirt — and that’s when it happened. Not gender euphoria, but sensory relief. Almost instantly, it felt as if the binder had enveloped me in a tight, comforting hug that instantly dissolved my worries and doubts about the life I was getting myself into. In retrospect, this now strikes me as odd — how could someone so sensitive to textures and clothing seams find comfort in a garment designed to compress and constrict? Compression has long been recognized as calming for autistic people (or for people with the relevant sensory processing difficulties associated with other types of ‘neurodivergence’). Weighted blankets and tight hugs stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system, helping to reduce anxiety and sensory overload. Binding, in its own painful way, seemed to give me that same kind of relief — a sense of control over the chaos of my own body.

Whereas the seam of a sock rolling below my toes as I walked would cause me to change my entire gait just to avoid feeling the unpleasant sensation, I found it shockingly easy to adjust to the discomfort of a tight garment compressing my ribs and lungs. This is the sensory paradox — autistic people are hypersensitive to certain kinds of stimulation but often seek out deep pressure because it helps calm the nervous system. Predictable discomfort is easier to tolerate than unpredictable chaos. Binding became a form of self-regulation, even though it was damaging my body slowly and irreperably.

“Unsafe Binding” Will Snap Your Ribs in a Week.

“Safe Binding” Will Painfully Contort Your Body Over a Decade, Without You Realizing:

The longer I wore the binder, the more damage it did to my body — and the less capable I became of noticing this damage as it crept up on me. In retrospect, I now find this paradox to be worthy of exploration:

How is it that someone who has such intense sensory discomfort surrounding textures of food, tags on clothes, and where the seam of a sock touches her toes could stomach the discomfort of binding her breasts, constricting her rib cage and posture for over eight hours a day, for weeks that stretched into months and into years? The answer, I suspect, lies in the power of compression to regulate sensory input. The pain of the binder was predictable. The relief it brought from the chaos of my sensory experience of life, and from the endless stream of consciousness generated by a mind incapable of ever turning itself off, was immediate. And that made the pain of breast binding feel like a tolerable sort of mild discomfort— even as it was doing me harm.

This discomfort I labeled “sex dysphoria” wasn’t purely intellectual (having to do with the social roles scaffolded onto members of the female sex) nor was it purely visual (I only cared about looking like a man, as opposed to just ‘masculine’ when my safety depended on ‘passing’); it was a deeply embodied, and at the time, ineffable discomfort.

Autistic sensory processing issues aren’t limited to how things look — they’re rooted in how the body physically experiences the world. Autistic people often have poor interoception, and struggle with the ability to sense internal bodily signals like hunger, pain, or the need to use the bathroom. This weak connection to the body’s internal state makes it harder to distinguish between discomfort rooted in sensory processing issues and discomfort stemming from deeper psychological distress.

When I felt uncomfortable in my body, it was easy to assume the problem was related to my sex because that was the only framework presented to me. I lacked both the maturity and the internal feedback mechanism to recognize that the source of my distress might have been solvable sensory issues rather than an intractable problem with my sexed body. Binding offered a concrete, external solution to diffuse any of the miscellaneous discomfort labeled as “gender dysphoria”— but it was a solution that misunderstood the root cause.

Wearing the binder certainly didn’t make me feel ‘euphoric’ but the compression made it easier for me to function in the sensory environment of a crowded college campus. I could sit in hours long classes under flickering artificial lights and as long as I ate lunch that day, I could miraculously emerge from a lecture without a pounding headache. I took my first in-class exams and the sound of hundreds of other pencils scratching on hundreds of papers as students worked against the clock, didn’t fill me with a nearly homicidal rage as the hours of studying I had done vanished from my memory– instead, I could tune out the cacophony long enough to finish the exam with a clear head.

As I began to bind my breasts with the ‘proper’ binder from an official company and in the right size, sure my arms would sometimes tingle or my back would ache after a long day, but I thought that wearing one in the right size meant that the binder wasn’t the thing causing these symptoms. Surely, I thought my childhood muscle tightness issues were inexplicably acting up again but on totally different sets of muscles. I’m not an idiot, I should have, despite my immaturity, been able to guess that it was the binding causing these odd symptoms, especially as they worsened over time. But I didn’t, until it was far too late.

Why Didn’t I Recognize the Harms of Binding Until it Was Too Late?

It felt as if my brain just ‘worked better’ even as I was probably depriving it of oxygen. I could wear shirts that previously would never have met my strict standards for fabrics, threads, seams and buttons I could tolerate feeling on my skin. Not only did the binder cover most of the skin which would have normally been irritated by the less than ideal texture of the fabrics of shirts gifted to me at on-campus trans clothing exchanges, but even on the skin that the fabric did touch, it no longer felt as if I was wearing sandpaper around my wrists. The compression made my body feel like a significantly more tolerable place to be.

It was not until several months after I stopped binding, that I began to truly understand how much damage it had done to my body. Over the course of those months, I was progressively overcome by pain in my breasts, ribs, and back that wouldn’t go away- some of it was the pain I was used to, and some of it was new. Without realizing it, I had changed the way I breathed while binding and now found myself unable to take deep breaths without pain.

While binding, the sensory relief of the compression outweighed the physical pain caused by it. Once I took the binder off, I was left with all of the years of accumulated pain and damage to those areas of my body– but without any of the soothing compression to cushion the blow. I was left to figure out how to support the weight of my damaged breasts on muscles which had atrophied over the course of the decade in which I did not use them, and with ribs that hurt to run my fingers over. No one had prepared me that this would be the outcome of a so-called non-invasive ‘gender affirming’ intervention. I often ask myself “you were in your body every day you bound your breasts- how did you not know what it was doing to you?”

The Sensory Paradox

For an autistic person or for anyone who struggles with any sensory processing disorders, predictable discomfort can be more tolerable than unpredictable chaos of an environment rich in sensory stimulation. When combined with the regulation of the nervous system through compression, this predictable discomfort of binding becomes very tolerable.

Connecting the Puzzle Pieces

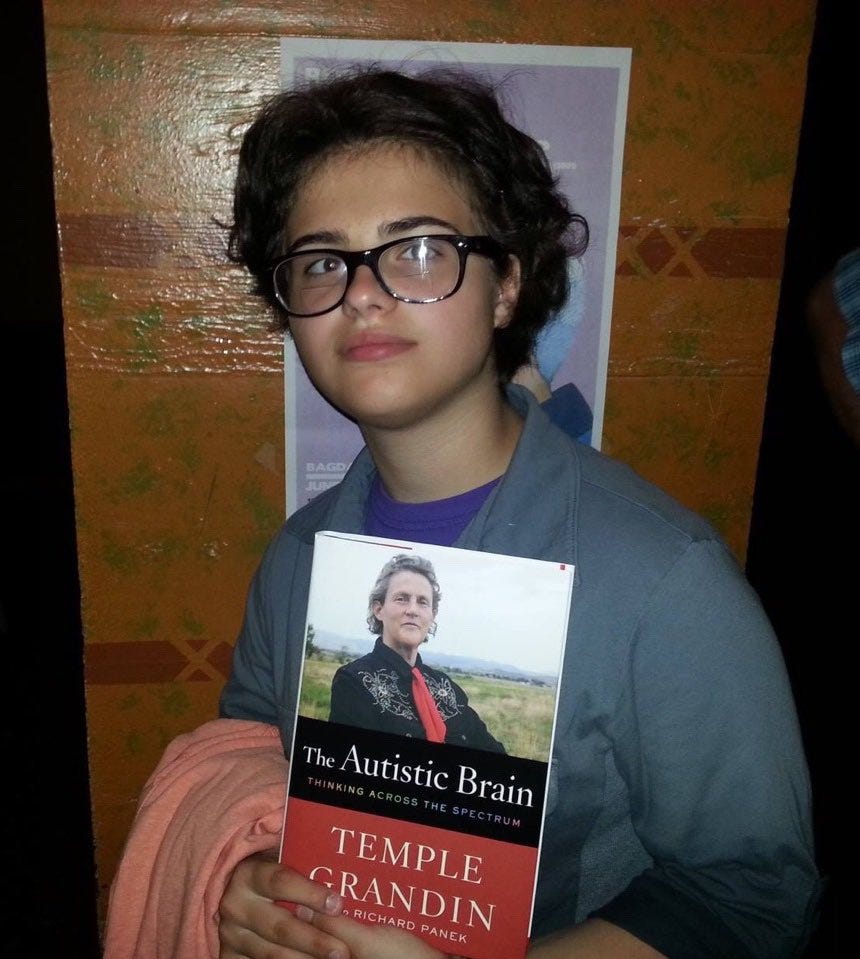

As I sit here writing this, I can’t help but kick myself for not putting these puzzle pieces together sooner. By the time I was 13, I was already obsessed with autism. While my peers fixated on One Direction and Taylor Swift, I was busy idolizing autism expert, Temple Grandin, and devouring everything I could find about autism.

I found nothing relatable about the celebrities my peers idolized, but everything about famous autistic people whose autistic fixation was autism— were the most relatable people I had ever encountered. I even volunteered at the local Autism Society at the age of 13, though I was quickly moved to data entry after the director realized that maybe between my fixation on rare pituitary tumors and on autism itself (with a notable inability to talk about anything else) I perhaps wasn’t the best fit to teach girls on the spectrum (aged 9-18) about the rules of ‘acceptable’ social interaction. What I thought was my first ever internship in autism research was, in retrospect, a clever way for the director to include me in the autism playgroup without me even realizing it.

I knew enough about autism and its comorbid conditions to suspect I was (what we’d call in the post DSM-5 world) autistic. I could see myself perfectly described by the diagnostic criteria for “Asperger’s” and was certain I could secure a diagnosis if I pursued one. My parents were unconvinced that labeling me with a pathology would help me improve upon the deficits it caused better than they could. In some ways, they were absolutely correct. But the bigger problem in my life seemed to be my attention issues and my total inability to focus in elementary and middle school classes — because we never talked about rare pituitary tumors or hyperlexia or autism, which were the only topics I cared enough about to actually pay attention to.

After trying everything in their power to help me without medication — putting me in a year-round school, spending a small fortune on extra tutoring, trying to patch up the obvious gaps left by my daydreaming about excising brain tumors in third-grade math class — my parents eventually reached the limits of what their parenting could solve. Instead of being diagnosed with autism at 14, I was diagnosed with ADHD and medicated for it — another condition I had already diagnosed myself with before the professionals caught up.

There are many overlapping traits between high-functioning autism and ADHD, but one of them could be managed with medication. Treating my ADHD improved my attention issues and even softened some of my more severe sensory processing problems. Being medicated for ADHD also made me realize how much I had been missing in social interactions — not just because I lacked the capacity to understand them, but because they were never interesting enough to hold my attention in the first place. Now that I could finally pay attention, I became painfully aware that I wasn’t living on the same planet as my peers. I had years of social learning to catch up on.

Some of my autistic traits were mitigated by the ADHD medication — but some key difficulties remained. And because I now had a pill that was supposed to “fix” me, I blamed myself for the things it didn’t solve. Despite understanding the diagnostic frameworks better than most adults around me, I was still a kid. Without a formal autism diagnosis, I never learned how my sensory processing issues were shaping my life — or even that they existed.

Why Are Clinicians More Likely to Diagnose Girls With Gender Dysphoria than With Autism?

Many girls who meet the criteria for level one autism (formerly Asperger's) aren’t diagnosed because clinicians are trained to recognize autistic traits as they appear in boys. The autistic mind craves answers and rigid frameworks to stand in for the social schemas it struggles to develop naturally. Parents often avoid a diagnosis because they fear the label will limit their child — and while that concern isn’t unfounded, the trade-off is that kids with undiagnosed autistic traits (like sensory issues, social difficulties, and hyperfixation) will try to find answers on their own. If they don’t receive an accurate label, they will search until they find one that fits.

In that search for answers, many autistic girls are diagnosed with overlapping but incomplete conditions — ADHD, OCD, anxiety, depression — but not autism. They know they’re different but don’t know why. The framework of gender dysphoria offers a compelling explanation:

If you have sensory issues that make the feeling of hair on your neck intolerable, and the transgender framework suggests that your discomfort with your body means you were born in the wrong one, cutting your hair feels like solving the problem. When the initial sensory distress goes away, it reinforces the idea that you were right to diagnose yourself with gender dysphoria— and clinicians who put the diagnosis on paper are unlikely to contest it.

The same logic applies to breast binding. Compression calms the nervous system and quiets sensory chaos, making life more bearable — even if the binder is physically painful and damages your body every day. The sensory relief convinces you that you’re treating your dysphoria correctly, which encourages you to try the next step: hormones, surgery, further irreversible interventions.

The problem is that treating undiagnosed autistic sensory issues through gender transition is like fixing a stain on the floor by smashing the floorboards with a hammer. You may solve some of your symptoms, but the ‘solution’ causes deeper damage that requires even more invasive interventions to address. When the original problem is rooted in undiagnosed autism, transition becomes a misguided solution to a misidentified problem. Binding may work to quiet your dysphoric inner dialogue, but not for the reasons you think it does.

That’s what makes breast binding and the transition pathway more broadly, so dangerous for young people: it’s possible to misattribute very real, embodied sensory discomfort to a psychological issue of “being born in the wrong body” — and to believe the “cure” is working, even as it causes long-term harm. Young peoples’ lack of emotional maturity and inadequate life perspective will only make them vulnerable to a doctor’s desire to quickly finish up diagnosing them, so they can see their next patient.

Conclusion

Teenagers who adopt trans identities aren’t trying to give their parents a heart attack, disappoint them, or make their lives difficult. They’re engaging in an earnest pursuit of self-discovery. Too often, non-affirming parents fail to understand that their child is genuinely trying to solve a problem. While the child may not reach the right conclusion about the nature of their discomfort or why they feel different from their peers, they aren’t wrong about all of it. You don’t live in your child’s head — and if your kid spends most of their time in their own head, you’re even less likely to understand their internal world.

This disconnect often shows up in arguments about timelines: The kid says, “I’ve always felt this way,” and the parent responds, “But you did all these girly things as a kid without any issue.”

There’s a grain of truth in both perspectives. The parent is correct to notice that the child hasn’t externally expressed any gender confusion (or even any non-conformity in some cases). The kid may be right when she says that she’s felt different for as long as she can remember (for as long as she’s had any self-awareness associated with basic logical reasoning skills). Perhaps that feeling of difference may have been some gender confusion, or perhaps it is totally unrelated. That feeling she’s describing to you as one she has always felt, isn’t necessarily a burning, intractable desire to medically approximate a version of manhood. It’s more likely rooted in differences in how her brain works and how she relates to other girls her age. That feeling is real.

But because she doesn’t understand why she feels the way she does, and because she has an insatiable, intractable hunger to fill in her still developing schemas with clear answers, she gravitates toward the closest available framework. Now she’s convinced she has finally found the answer and she will say or do anything in her power to solve the problems of her discomfort and she cannot understand why her parents are so concerned about the seeming panacea she has discovered after consuming hours of trans- related content.

In many ways, the transgender identity framework functions as a metaphor for the struggles, strengths, and weaknesses of someone with undiagnosed and untreated (high functioning) autism. But that’s a subject for another essay.

Have you enjoyed this article? If so, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work so I can continue to bring my insights to you.

I also offer parent coaching. If this is something you are interested in, DM me.

Incredibly in-depth and highly valuable. I wish for pre-teens to learn about you and your story.

As a therapist and theatre teacher, my mind goes to kids’ self conception and how the theatre can help reach them: I picture a “one woman show,” your autobiographical presentation on a stage, with invited 5th grade and middle school classes.

I wish I could share your story with 10-12 year- olds, before they fixate on GD and interventions such as breast binding as the way to manage their sensory discomfort and dissociation.

Teachers need to learn your story too, so they can understand body discomfort and lack of sensory attunement through a wider lens.

I greatly appreciate your courage and dedication, and your willingness to disclose your deep and personal feelings, inquiry, and journey. 🙏🏽

Thank you for sharing this. I experienced so many "oh, I see moments" while reading this. No one has ever explained what is actually happening inside the head of a young autistic person the way you have. ( I have read many autobiographies of autistic people). Add to that the feeling of being born in the wrong body - no one has ever explained that so well and in such a relatable way. As you say, no parent can ever see what is happening in the head of their children but your posts can give us some inkling as to what