How Transition Makes Dysphoria Worse Without You Realizing It

One Detransitioner's Perspective

For those grappling with gender dysphoria, transition is often presented as the only viable path to relief—a linear journey from suffering to self-actualization. The dominant narrative insists that transition, whether social, medical, or surgical, will align the mind with the body, ease psychological distress, and allow a person to live authentically. But what if that story isn’t always true? What if, for some, transition not only fails to alleviate dysphoria—but quietly deepens it– without them even realizing?

This question is difficult to ask, let alone answer. To even entertain the possibility that transition could worsen dysphoria feels taboo. It risks being labeled as “internalized transphobia,” or dismissed as the product of outside pressure. Yet for a growing number of people—particularly those who detransition—this question has become not just legitimate, but a hauntingly personal reality to contend with. I would argue even that anyone who is certain that transition will resolve their distress, even if they feel it already has, should read this essay– as it will provide insight into a phenomenon which occurs commonly during transition, but is hardly discussed honestly within trans communities themselves.

The Allure of Certainty

In a world that increasingly views gender identity as innate and immutable, transitioning can feel like a promise: change your body, and your mind will follow. For many, this promise is not just hopeful—it’s urgent. Dysphoria can be a terrifying experience: a sense of wrongness, disembodiment, disconnection. It’s no surprise that people in pain will grasp any solution, especially when the solutions are framed as life-saving.

But transition doesn’t always offer the clarity it promises. In some cases, it introduces a new layer of complexity. Hormones can bring their own psychological shifts, not all of them positive. Surgeries have side effects—both physical and emotional—that are rarely discussed in full. And sometimes, the pursuit of bodily congruence can become a moving target which brings about new types of incongruence which one may have never even be to able to predict. You change one thing, then another, always hoping the next step will bring peace. But what if it doesn’t?

When Coping Becomes Confinement

For many, the distress which will catalyze their gender transition doesn’t begin as a perfectly articulated desire to become the opposite sex. Transition is a coping mechanism—for all kinds of miscellaneous, amorphous distress. Sometimes that distress is connected to the sexed body, but just as often it isn’t. It may come from a broader sense of social unease, trauma, disconnection, depression, anxiety, neurodivergence, or simply the experience of not fitting anywhere. Transition, in this context, offers a compelling framework: This is why you’ve always felt off. This is how you fix it.

And for a time, it can work. The symbolic power of changing names, pronouns, clothing—these acts offer control, clarity, direction. But with that shift comes something else: a whole new standard to meet. From the moment you begin transition, you may temporarily solve your distress about being seen as your natal sex—but new forms of distress often take its place.

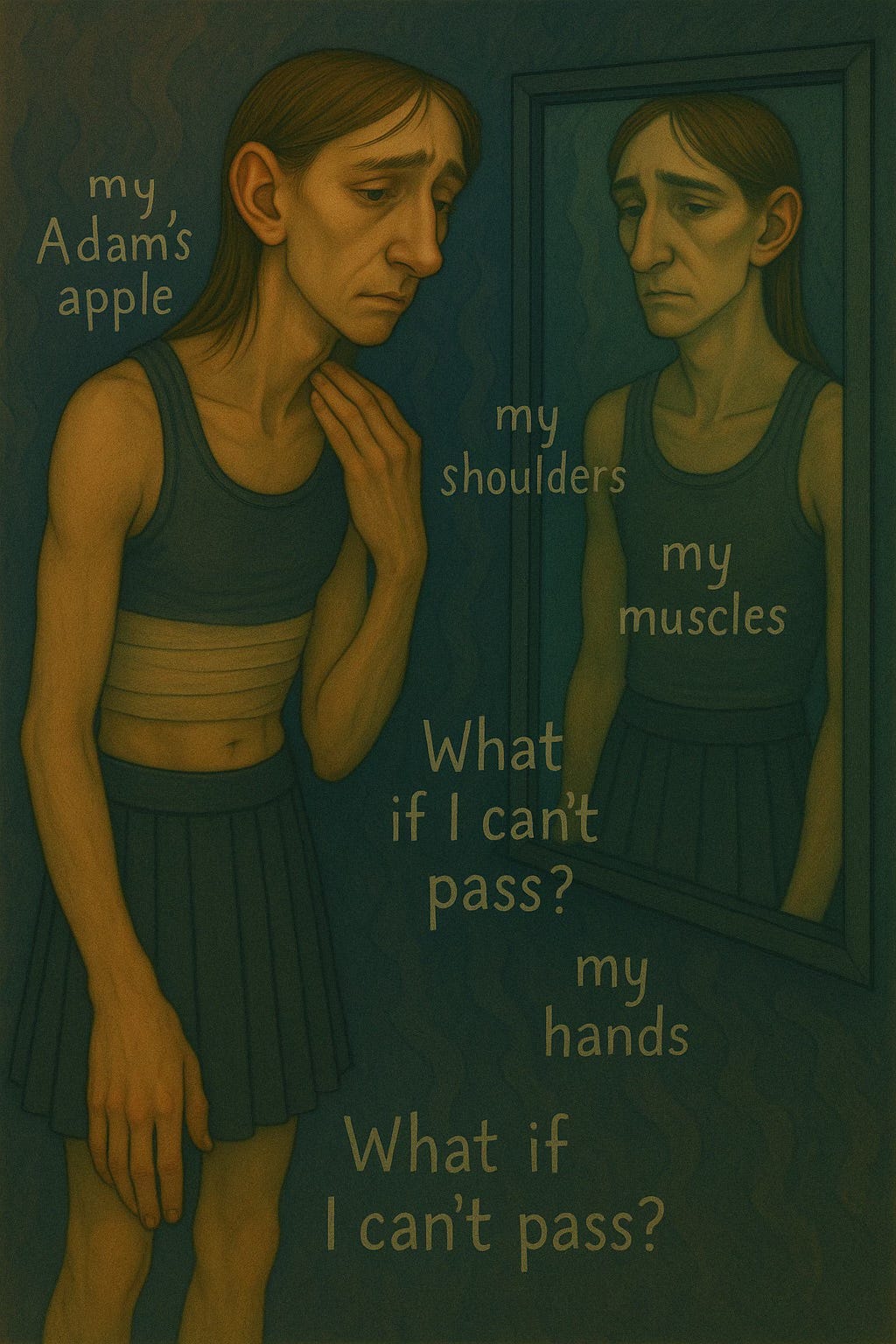

Even something as simple as getting dressed becomes fraught. What once could have been a joyful, expressive process—choosing clothes that reflect your personality, experimenting with textures and styles—now becomes an exercise in strategy. Instead of “That’s a cool shirt, I like the fabric and the cut,” the question becomes, “Does this shirt hide the lines of my binder? Do the patterns make me look taller or shorter? Is the design busy enough to obscure what the binder doesn’t bind? Do the shoulders look wide enough? Are my hips too obvious?” You might begin layering—wearing a shirt unbuttoned over a t-shirt—to visually offset your feminine shape.

And then the inevitable trade-offs: If I want to wear this men’s-style shirt and button it up over my chest, I’ll need to wear a binder. If I don’t, I’ll have to size up, which means the shirt will be too big in the shoulders and too long in the sleeves—and it won’t look right. Suddenly, what should be a normal part of adolescence—trying on clothes, playing with identity—becomes heavy. High-stakes. Exhausting. All consuming.

When your wardrobe becomes a battlefield for passing, it stops being a reflection of self-expression and morphs into a shield. Every morning, you’re not just getting dressed—you’re suiting up, trying to protect yourself from being seen “wrong,” from being found out. There is no space for lightness, for trial and error, for “just liking something.” Because the wrong choice might betray you. It might ‘out’ you. It might unravel everything you’ve worked so hard to build.

What began as a coping mechanism for distress becomes a kind of confinement in its own right. The calculus shifts, and suddenly, everything is filtered through one oppressive question: Will this make me look like who I think I am on the inside? And the longer this pattern continues, the harder it is to remember who you were before that question took over your brain space, and then it will reach every aspect of the way you live your life.

How Transition Escalates Dysphoria

Often, gender dysphoria begins in a narrow, specific way. You might feel distress about one part of your body—a flat chest, a big chest, wide hips, narrow hips, a high voice, a deep voice—or discomfort with a particular role, like being perceived as “girly” or “boyish,” or being expected to date, dress, or behave a certain way. That distress may feel consuming, even existential. And when you hear that these feelings are signs you’re transgender, that you were meant to be the other sex, transition starts to seem like the obvious solution.

But what often goes unspoken is how transition—especially social transition—can subtly shift the focus of your dysphoria, and even deepen it.

When you start socially transitioning, you’re not just escaping the discomfort of being misread—you’re stepping into a whole new identity, one with its own expectations and comparisons. If you begin to live as a boy or a girl, a man or a woman, you inevitably start looking to others of that sex as models for what you’re supposed to be. Suddenly, you aren’t just trying to feel less alienated in your own skin—you’re trying to become something that your body, your history, and your biology may not allow you to fully embody.

This comparison can become relentless. You may start asking: Do I pass? Do I look enough like a real man or a real woman? Do people see me the way I want to be seen? And when the answer is no—or when you fear it might be—you may start scrutinizing parts of yourself that didn’t even bother you before. Your voice. Your bone structure. Your height. Your skin. Your hips. Your genitals. Things you used to live with now become problems to solve.

What began as a focused discomfort—a dislike of your chest, or unease in a specific social role—can metastasize into a broader, more global distress. Why? Because the bar has been raised. You’re no longer just trying to feel better in your own body—you’re trying to be a different kind of person entirely. And the more you try to match that ideal, the more you may notice the ways your body refuses to comply. What starts out as an earnest attempt to mitigate a type of self-perceived incongruence between the mind and the body can turn into a different type of incongruence: an incongruence between who you fundamentally are and who you are trying to become.

On the flip side, for some people, their dysphoria starts as broader, more global distress which isn’t related to a specific sexed body part or social role, but due to a variety of other life factors. For females, they may begin to attach a history of experience of sexual assault to those specific parts of their bodies which now feel alien and wrong. In this case, the broader feelings of insecurity and lack of safety in one’s own sexed body will be projected onto an ‘offending’ physical body part. This too isn’t unique to the experience of gender dysphoria. We also see this in a wide array of body dysmorphias and eating disorders.

Some transitioners may not feel much (if any) gender dysphoria before they embark upon the process of transition, but rather that they are trying to meet a developmental need or to explore some other aspect of themselves or their inner world– but that when they are told to “try experimenting with a new gender identity, with a new name and pronouns, and see how it feels”-- they now they begin to experience dysphoria where they never had previously, and will jump into transition head first to solve it— simply because “trying on a new identity for size” has been suggested to them.

For male transitioners who are not exclusively homosexual—those who are heterosexual, bisexual, or asexual—there is often (if not always) an underlying erotic drive to feminize themselves or live as women. This is a paraphilia known as autogynephilia (“love of oneself as a woman”), and it’s frequently accompanied by autoandrophobia—a deep discomfort, even repulsion, toward their male bodies.

As a paraphilic condition, autogynephilia is poorly understood, not only by the public and gender clinicians, but often by the transitioners themselves, who fail to recognize it as the root of both their dysphoria and their gender euphoria. The trans community has overwhelmingly dismisses the legitimacy of this theory, because acknowledging it would require them to recognize themselves not as the women they desire to be in their fantasies, but as men with a uniquely male paraphilia. They instead conceptualize of their paraphilia and associated body dysmorphia as evidence that they’re “really women.”

In the past, most autogynephilic men would have limited their cross-gender identification to private crossdressing, with only the most distressed seeking transition later in life. But in today’s affirming culture, increasing numbers are transitioning at much younger ages. My friend Ray Alex Williams is a detransitioned man who discusses his experiences with autogynephilia on Substack, on YouTube and on Twitter, and is a brilliant voice of analysis on this topic. I highly recommend watching his recent interview on “Beyond Gender” where he discusses the escalation of dysphoria experienced by many autogynephiles once they begin to transition.

Paradoxically in any of these cases, the very act of transitioning can heighten your awareness of the things that separate you from your target identity. You may find yourself more obsessed with gender than ever before. More sensitive to slights such as ‘misgendering,’ more attuned to whether others “see you right,” more likely to interpret awkward interactions as personal failure. At this point, the dysphoria becomes less about how you feel and more about how you compare—how you measure up to an increasingly impossible standard.

This is one of the most painful truths rarely discussed: that transition can create new dysphoria even as it tries to relieve the old. And when you’re in it, it’s hard to recognize this shift. Because all you’ve been told is that more transition equals more relief.

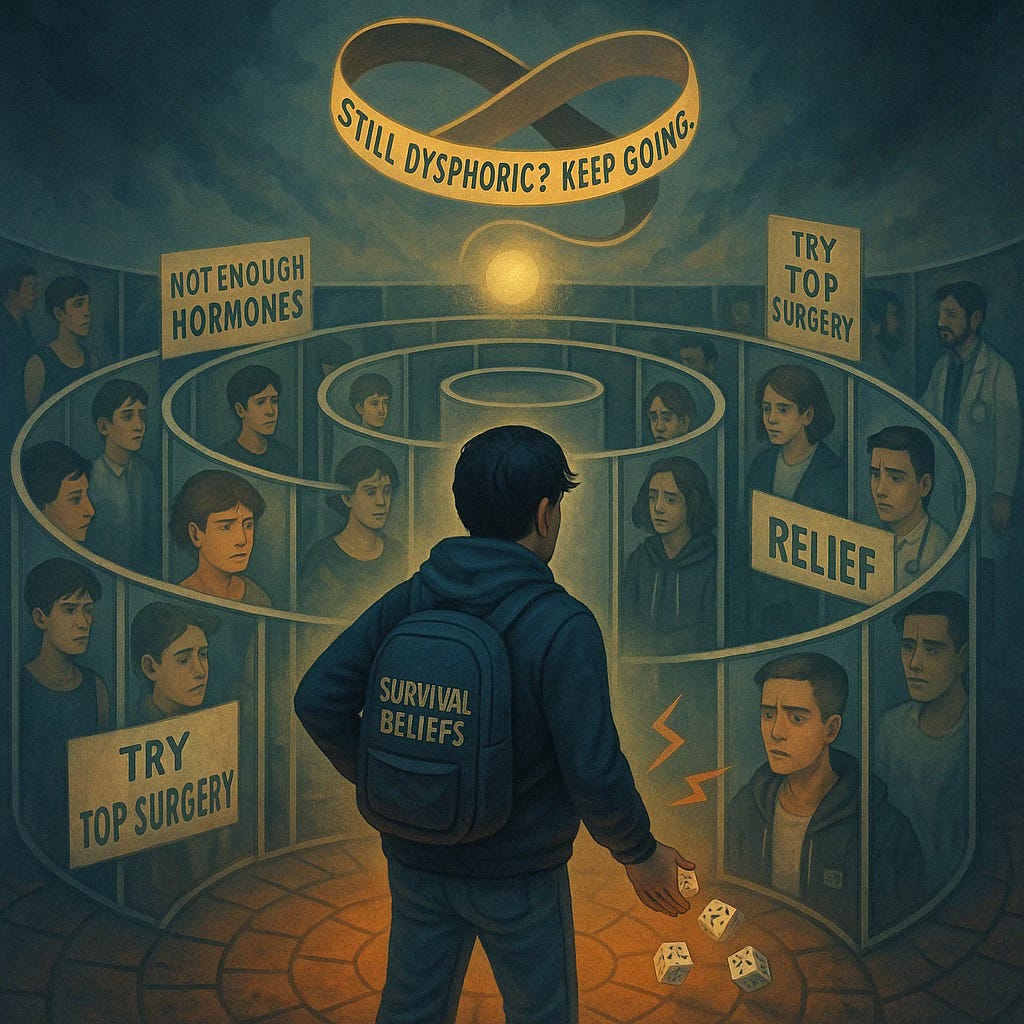

To their credit, trans communities often discuss that “not all trans people want (or need) hormones, or surgeries. They will say that some people may want a social transition with low doses of hormones, high doses of hormones, or no hormones at all. Some may just want ‘top surgery’ (removal of breasts for females or silicone implants for males) while others may want genital surgery, facial surgery or voice surgery. But there’s no guidance provided about how one is supposed to know that any given intervention will be the “right one” because this is only something that “each trans person can know for themselves.”

The medical establishment just goes along with this model without asking any questions aimed at giving the patient clarity about why they think that such an irreversible, risky and uncharted path is their only path to happiness.

There are no metrics by which to gauge whether transition actually is resolving an individual’s distress. There are no guidelines, no shared criteria for success or wellness. You're ushered into this pathway within communities that love bomb you, but you’re left alone to navigate a medicalized identity with no roadmap except to continue it indefinitely in the hope it makes you feel better. Beyond that, there’s no clarity, and often no real support when you say, "this isn't working.”

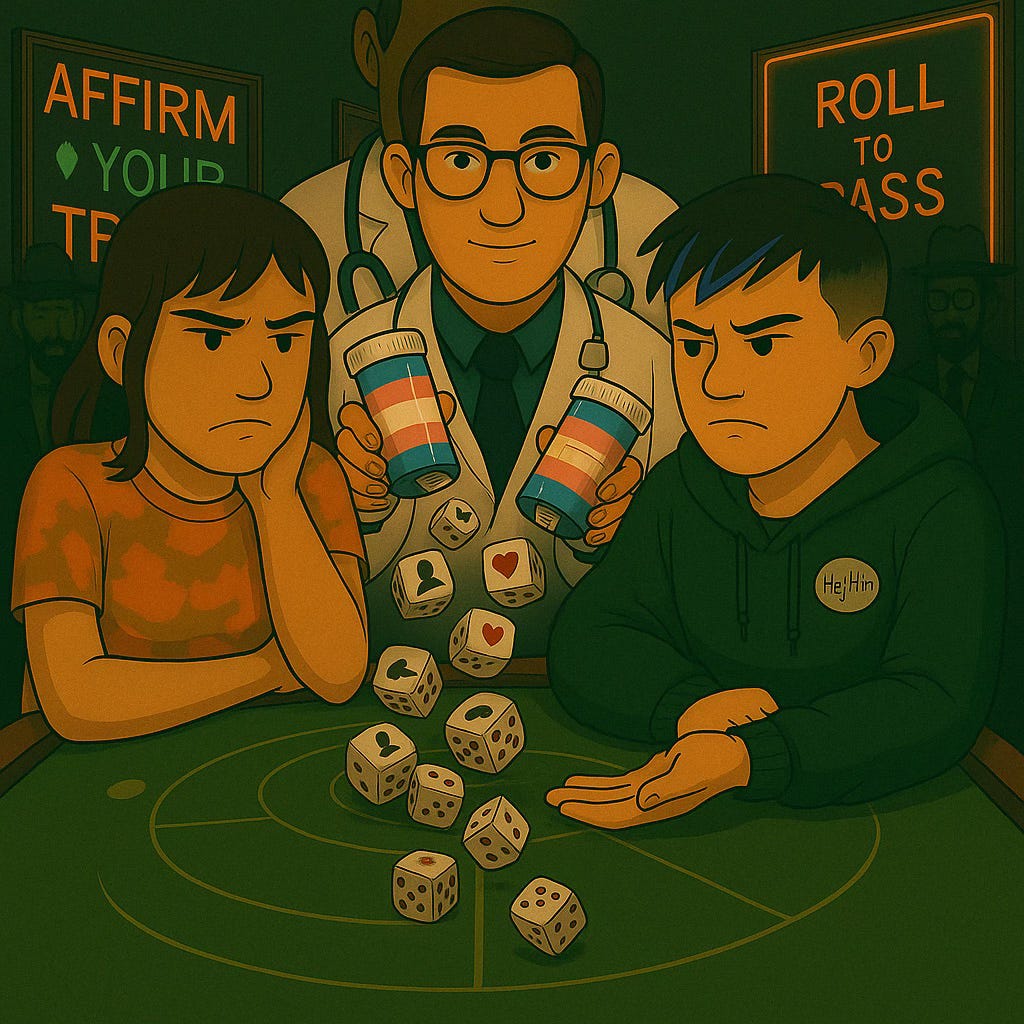

Mr. Potato Head ‘Rolls the Dice’ Gender Medicine

Within the framework of gender medicine, the body is often treated like a Mr. Potato Head—composed of interchangeable, customizable parts. It’s easy to intellectualize which modifications you might want, or what features you’d prefer to tweak. But at the end of the day, it is you who will have to live in that body. The human body is a set of interconnected systems, and modifying one part of it will cause functional issues in other areas, many of which are often unpredictable and unknown to the doctors prescribing these interventions. The consequences of these changes aren’t always immediate—especially if you’re young, healthy, you have ADHD or are autistic, and struggle with interoception. These factors can make it difficult to form a grounded sense of what transition will actually feel like, and what trade-offs it will require.

For some, transition may be a pathway they can adapt to quite functionally for several decades. I suspect these transitioners are in the micro-minority of ‘old school transsexuals’ who didn’t go into transition within a system which allowed the patients to dictate their entire treatment protocol, and where histories of extreme trauma, mental illness and sexual assault would have automatically excluded them from further irreversible intervention. Even for this population, it is hard to say that transition was a requirement for their flourishing— we simply don’t have evidence attesting to this assertion.

For many, if not most of the transitioning people I have met, who have transitioned within the last decade and a half where every possible cautious measure has been abandoned due to activist pressure rather than proof that these are best clinical practices— will express that transition brings short-term relief, while also introducing new problems they couldn’t have anticipated. And because transition carries significant costs—socially, physically, and psychologically—very few people are given the tools or space to pause and ask, soberly and without ideology: Is this actually helping me function better in my life?

Today, transition is a path often undertaken—sometimes for years—without thorough counseling to explore the many ways transition might fundamentally alter the course of a person’s life. And it’s not a given that those changes will be for the better. Long-term transitioners like Buck Angel, a personal friend of mine, have spoken openly about this uncertainty created by today’s gender affirming, zero exploration landscape. Whether the benefits of transition will outweigh the costs is often more like a roll of the dice than a decision grounded in any precise or predictive science.

Buck Angel describes having transitioned over three decades ago, and being a ‘guinea pig.’ Transitioners of Buck’s generation were informed that this path is risky, experimental and uncharted. The so-called ‘science’ underpinning Buck’s transition is no less experimental now than it was then, but these days, gender medicine is being framed as “settled science” by the very gender doctors who are supposed to accurately inform their patients about the nature of their condition, and about the available treatment options.

The limited availability of primary studies that independently assess the physiological effects of estrogen in males and testosterone in females represents a significant gap in the evidence base, as interactions between the administered cross-hormones and biological sex substantially alter patient outcomes. Telling transitioning patients that they are embarking upon a safe, well-tested path is medical negligence at best, and at worst, medical fraud. Patients deserve to know the known negative impacts of these interventions, while also being told that most of the long-term risks are still unknown. Not because that reflects my agenda, but because it reflects reality as it stands.

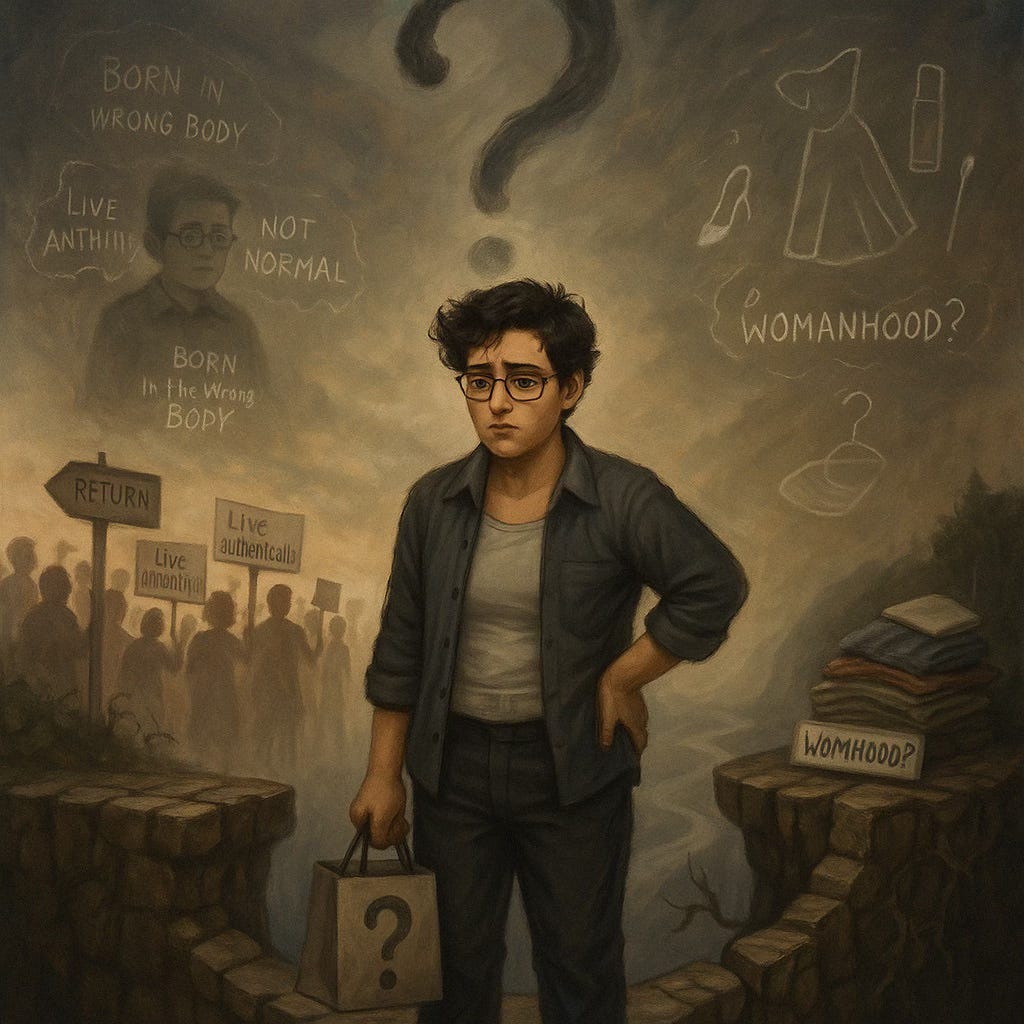

Many people enter transition full of hope, but also blindly—especially if they are young, developmentally immature, or in acute distress. It’s common for someone who has just adopted a transgender identity to begin reframing their entire past through that lens. This isn’t unique to being trans; it’s something we often see when people adopt a new worldview, religious belief, or psychiatric diagnosis—they search their memories for signs that this new framework explains everything.

The transgender framework is the most accessible and widespread sense-making system. It offers a simple and socially validated narrative: if you feel uncomfortable in your body, or in the expectations placed on you because of your sex, you’re probably trans. And if you’re trans, social and/or medical transition are your only path to reconciliation with yourself. But what the transgender framework doesn’t offer is a compelling explanation of why this is the best, let alone the only path to take—or how, exactly, these body modifications supposed to bring your body and mind ‘into alignment.’

So if you’ve been in transition and you’re still suffering, the answer given by everyone is that you must go further.

But maybe the problem isn’t that you haven’t gone far enough. Maybe the problem is that your suffering changed shape—and you just didn’t notice.

Lack of Interoception as a Barrier to Self-Understanding

There are countless ways transition can make someone more miserable in their body, even as they believe they’re on the right path. Often, initial relief or euphoria fades over time—not because transition has “failed” necessarily, but because the root causes of distress were never fully explored or treated. In many cases, generalized discomfort becomes fixated on specific body parts or social roles. And for autistic people—or those with ADHD—this process can be even more confusing.

Autistic individuals often report a baseline sense of disconnection from their bodies. The more cerebral you are, the more easily overwhelmed by sensory input, and the more you struggle with interoception, the harder it is to make sense of why you feel wrong in your own skin. When the nervous system is dysregulated and no one is helping you address that directly, you may seek out transition as a kind of workaround. You bind your chest. You add hormones. Each of these introduces new sensory experiences—some pleasant, some distressing, most of them layered on top of an already-fragile system.

If you struggle to identify when you're tired, hungry, anxious, excited, or sad, you're even less likely to be able to decode the strange, new sensations that follow using compression garments to bind your breasts, tuck your genitals, and those which come along with medical transition. And so, the mind kicks in to compensate. You begin to intellectualize—constructing a narrative to explain what you’re feeling. But if the framework you’ve adopted can’t actually account for the origins of your distress, it’s easy to misattribute your emotions to the wrong causes.

In my own case, transition was an intensely sensory experience. Binding, for example, was both painful and relieving—its compression soothed me, even as it created new discomfort. But the deeper sensory conflict came not from the physical tools of transition, but from the daily, lived tension of trying to exist as a member of the opposite sex. Whether I was in a conservative town or a queer-friendly city, the strain was the same: constant, emotional noise I couldn’t parse.

Why Do So Many Autistic Girls Bind Their Breasts?

Less than a week after graduating from high school, I celebrated my 18th birthday at an indoor trampoline park with a few of my closest friends. We spent the afternoon climbing ninja courses, doing front flips into foam pits, and throwing foam balls at one another- jumping …

It wasn’t until I was alone, under a weighted blanket in my room, that I could finally think clearly. That pressure—simple, grounding, physical—calmed my nervous system just enough for me to reflect without panic. It gave me access to a quieter mind, one not ruled by dysregulated input or the panic of touching cognitive dissonance. It was in that stillness, not in any ideology or identity, that I finally began to think flexibly—to open myself to entertaining my own doubt, to grappling with discomfort, and to an eventual conclusion of clarity.

Adapting to Transition vs. Resolving Gender Dysphoria

It’s possible to adapt to transition in a highly functional way, without ever resolving the original distress. I know this, because it is exactly what I did. The mind is capable of remarkable contortions to maintain a belief system, especially one that feels tied to survival and identity. If you’ve been told that transition is the only way to feel better, you may begin to interpret your ongoing discomfort as a sign you haven’t transitioned enough—rather than a sign that the process itself may be flawed, or that you went into transition without an accurate understanding of why you experience dysphoria and didn’t get the right treatment.

This can create a feedback loop: dysphoria leads to transition, transition leads to new or compounded distress, which is interpreted as more dysphoria—thus reinforcing the need for further transition. It becomes nearly impossible to separate cause from effect, treatment from symptom.

No Framework for Doubt

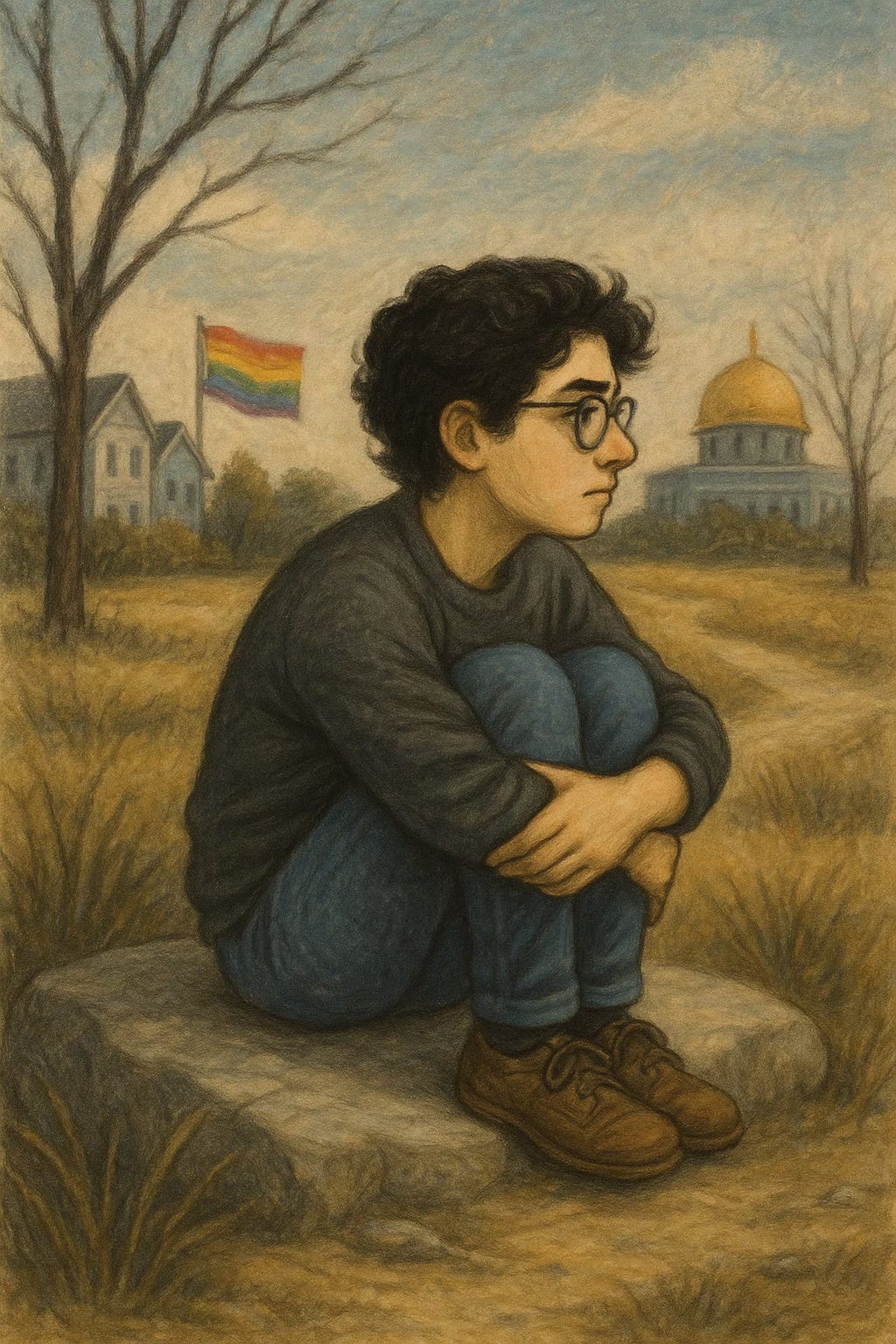

Another barrier to recognition is the social and psychological cost of doubt. Once someone has publicly or medically transitioned, questioning that choice can feel like betrayal—of one’s self, one’s community, one’s past decisions. The sunk cost is high, not just financially but emotionally. Doubt becomes dangerous, especially when your identity, your social support, and perhaps even your safety are tied to staying the course.

This can lead to a kind of emotional dissociation: rather than exploring whether transition is helping, you might become more invested in proving that it is. You learn to suppress the discomfort, to rationalize your pain, to frame your struggles as just part of the journey. All the while, the original dysphoria may be mutating—not disappearing.

It will force you to stop listening to your gut. Normally, if something ‘feels wrong’, that’s a signal to re-evaluate the decisions you are making, rather than as an inconvenience to be intellectualized away through mental gymnastics. In trans communities, this pattern of rationalizing away gut feelings is very common. It is something that female transitioners and male transitioners almost certainly experience differently.

Within these communities, people are often taught how to ignore their gut feelings. This happens on multiple levels, from individual doubts being framed as ‘internalized transphobia’ to the way that predatory behavior is handled in these communities.

Conclusion: Could Transition Make Someone Miserable, Without Them Even Realizing It?

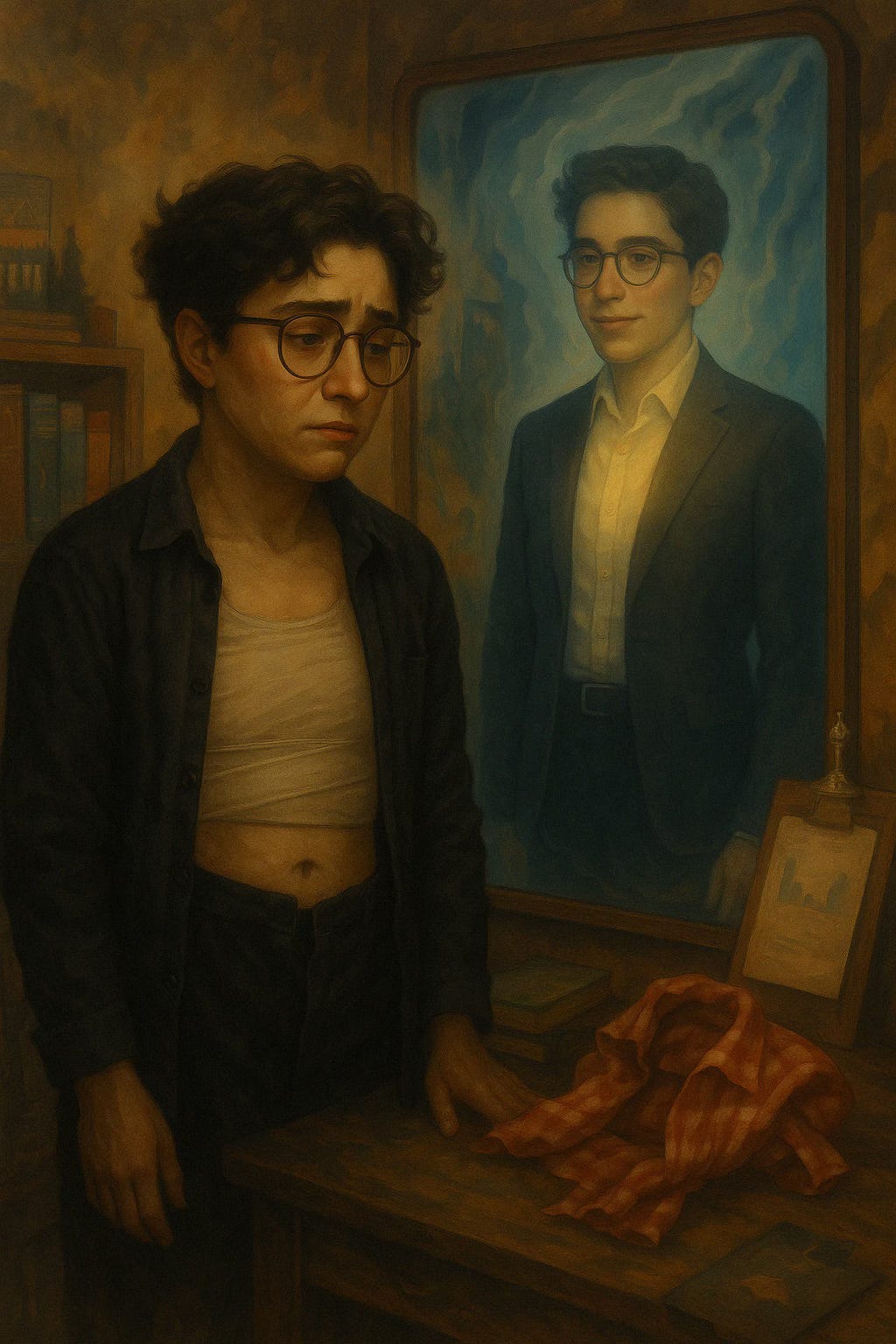

From my personal experience, yes— it is very possible that transition could make someone more miserable than they were before, without them even realizing it. In my experience, this occurred because transition did alleviate some of the difficulties I faced. It was also one hell of an adventure. Being perceived as a guy allowed me to live more freely within a traditional, religious society than I would have been able to live if everyone knew I was a woman. I felt safer walking down the street at night and more at ease in Arab neighborhoods and cities. I could have relationships with women without constant scrutiny or questions, and frankly, without the danger this would bring in certain subsections of a very traditional, religious, Middle Eastern society. I could have male friends who would treat me like one of their own. I was no longer bombarded with comments like, "You’re so beautiful—you’d look amazing in a dress. Why won’t you put on some makeup?" For once, I could exist without constant imposition from others about how I should look, dress, or behave—something I’ve always found intolerably intrusive. Binding my breasts made the masculine clothing styles I enjoyed for their functional ‘no-fuss’ benefits, to fit more comfortably. My shirts no longer had to accommodate breasts, so they fit better overall. The binder, despite actively destroying my body, also helped me regulate my nervous system and reduced other forms of sensory discomfort through physical compression.

But transition brought new problems I had never anticipated—and ones no one had warned me about. I now had to manage a double life: people who knew me before transition, people who met me during transition, and the anxiety of what might happen if those worlds collided. I began living in fear of being "found out." Social transition, I realized, had a shelf life. I couldn’t foresee how I would maintain the illusion indefinitely.

Even as I integrated into society as a man, I was haunted by the incongruence of returning home, taking off my binder, and confronting the reality of my female body. Over time, my body began to ache from binding—back, shoulders, arms. I had for years been intellectually committed to following all the guidelines for “safe binding,” (there’s no evidence that these practices can be done safely) but the demands of daily life made strict adherence impossible. I couldn’t just take off my binder when the arbitrary eight hours a day had elapsed. Passing as male became a requirement, a safety measure, a professional necessity. I was constantly anxious about being exposed.

I write about this extensively in my essay “Social Transition is Not a Neutral Act”— available here:

Social Transition is Not a Neutral Act

When we talk about the risks of youth gender transition, most of our attention goes to puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and “gender-affirming” surg…

When doubts crept in—about whether this was truly the path to my best self—I had no roadmap. I had spent my formative years trying to erase every sign of my biological sex. Everyone knew me as male. When I confided in a friend who had always known I was female, she asked, "Well, what would it even mean to go back to living as a woman? Are you going to start wearing dresses or something?" I didn’t want that. I transitioned in part to escape those suffocating expectations. But I also knew that un-binding would confuse the people around me. I’d have to buy new clothes. I couldn’t imagine how to exist in my female form without trying to alter it, because from the age of 12, I was fed a steady ideological diet that told me that every non-conforming thing about me needed to be changed for me to be a socially acceptable female, and that every normal aspect of my embodied female aging experience that I did not enjoy, meant that I was supposed to have been born male.

Transition wasn’t a wholly negative experience. As someone who is naturally gender nonconforming, it did solve many (but not all) of the initial problems I hoped it would. But it just wasn’t sustainable. It was a pathway that took a sledgehammer to so much of my life already, and it was already harming my body for years— even though I didn’t eat from the entire menu of ala carte gender affirmation interventions. I knew I couldn’t live this way forever without incurring greater and greater costs. And paradoxically, it also felt impossible to stop. I had believed transition would fix everything—just as many others do. When it didn’t, I had no idea what to do next. The trans community often frames any of its issues as society’s fault, and any doubts as "internalized transphobia." But no framework is offered for self-reflection, or for being flexible and critical about the many uncertainties pertaining to the risky path you’re on. There’s little space to pause and ask: Is this still working for me?

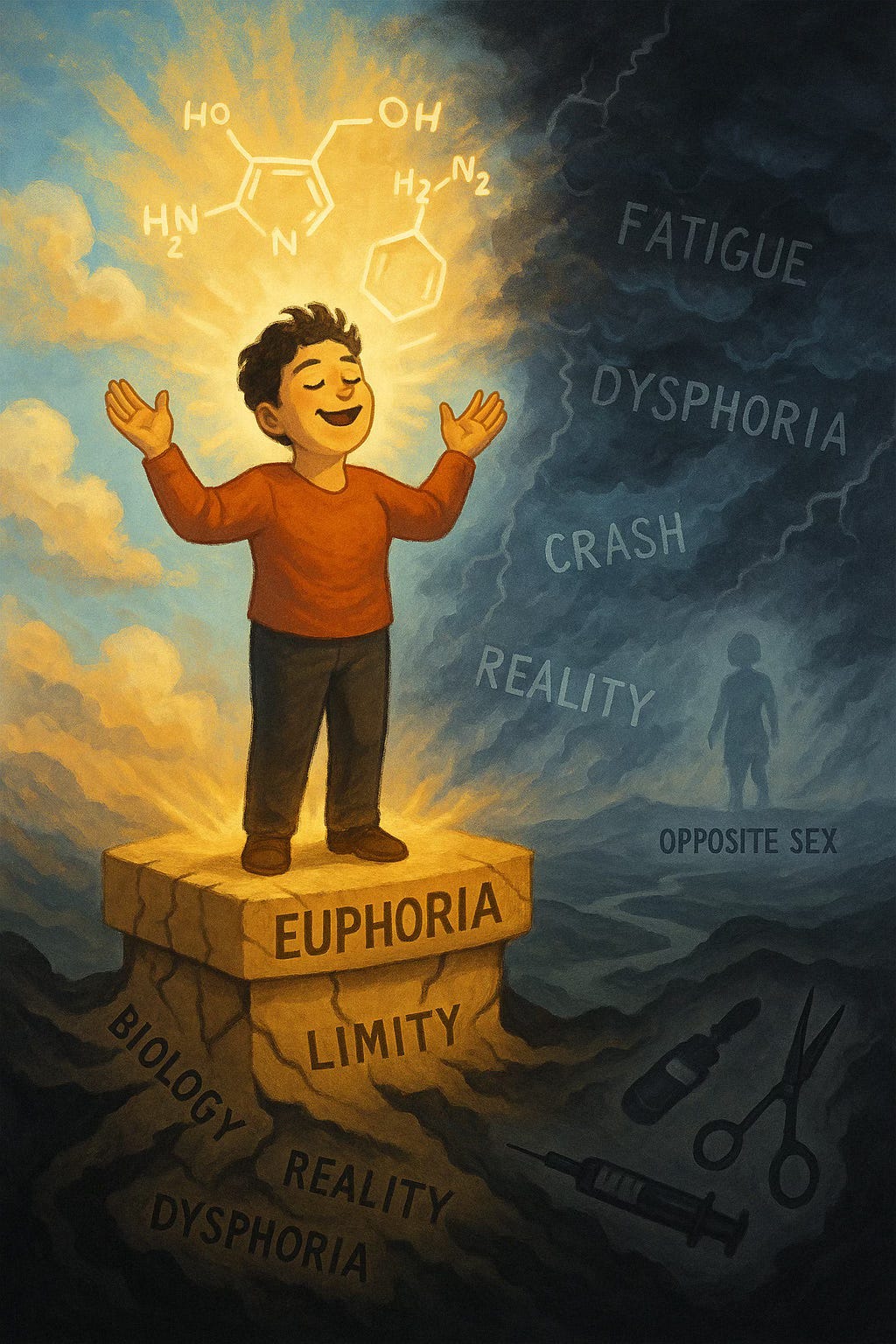

Through both transition and detransition, I came to understand that the human condition is inherently messy. Whether or not I stayed trans, I would still face some kind of inherent human suffering. All bodies come with limitations—whether related to sex, disability, or neurological differences. Some of those limitations can be worked with. Others simply must be accepted. It’s possible to find relief within our bodies, to improve our lives, without chemically or surgically altering ourselves. Often, our attempts to override biology bring short-term relief—or even euphoria—but the long-term costs can be so steep that you wonder “How the hell did I get here?” When regret sets in, it’s often because something irreversible has been done.

In time, I realized that my trans identity had become a barrier to self-acceptance. It became a shield against traumas and insecurities I had experienced in my past, and it only predisposed me to enduring further traumas and new types of insecurities. Continuing to change my body in search of ease was beginning to cause more problems than it solved. The initial benefits were being increasingly eclipsed by long-term harm. I suspect this is true not only for those who detransition, but also for many who continue on the transition path. When I finally confronted the reality that this life—one I had fought so hard to build—wasn’t freeing me but consuming me, I had to step back. I needed a new framework.

Before I could even stop transitioning, I had to admit the truth to myself: I was born female, and I would die female, no matter what I did to my body. I had to rethink what it meant to be a woman—not as someone who needed to marry a man, wear dresses, wear make-up or act a certain way—but simply as someone born into a female body, and grew into adulthood. That fact would never change. I had to get away from my non-gender affirming parents, my affirming LGBTQ+ community, and from my life in the Middle East where everyone knew me as male. I needed space, alone, to think clearly—away from the agendas and expectations of others.

Once I understood that I didn’t have to change how I looked, dressed, or acted to be a woman—that I already was one—I could finally begin to let go of the identity fixation. I could stop chasing an idealized life, free from the condition of female embodiment, and start simply living as the person I was always meant to be.

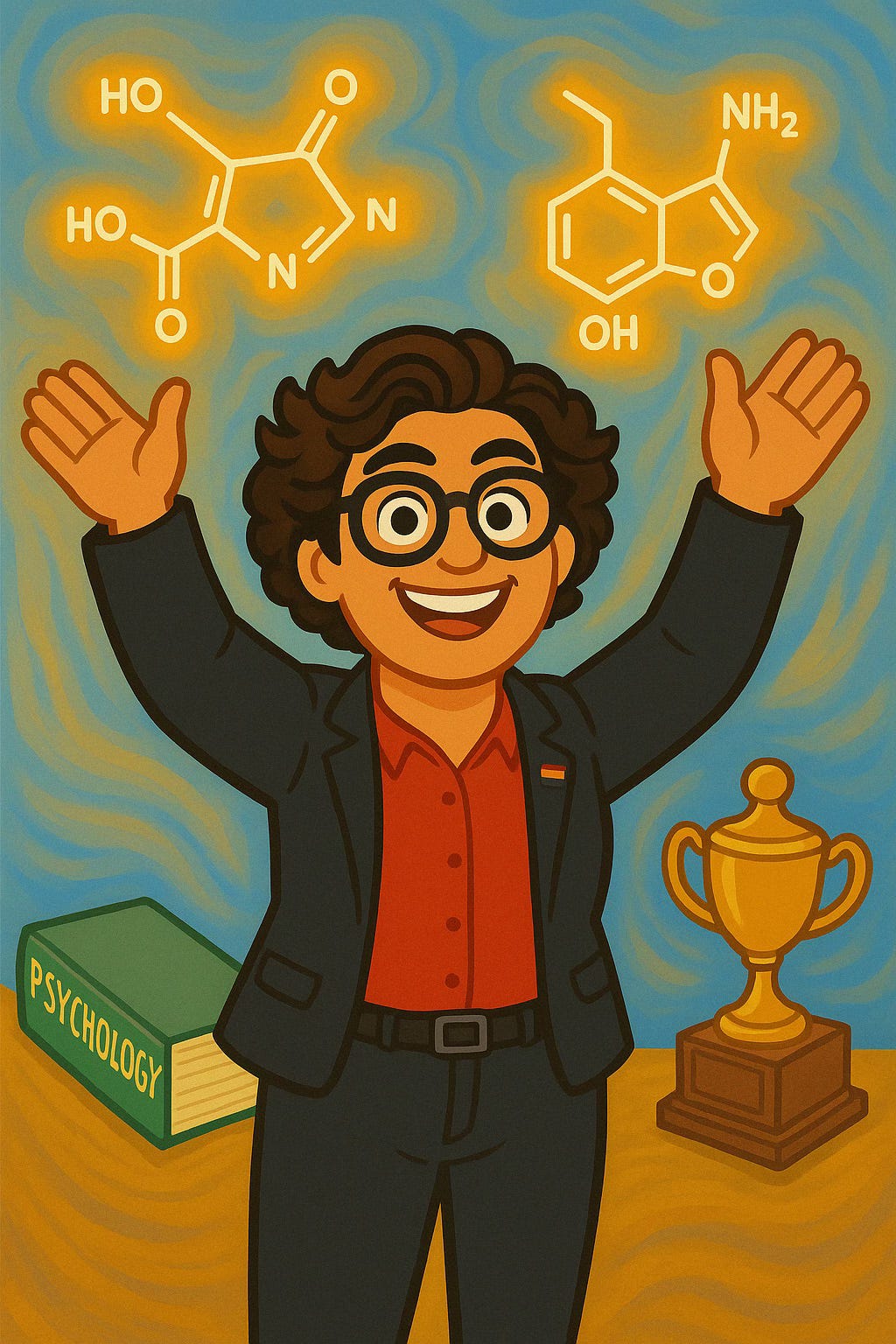

The truth is, feelings like euphoria or relief aren’t ‘trans feelings.’ They’re feelings that everyone experiences when they do something that brings them joy, or when they’ve taken an action which temporarily quells their existential pain. Feelings like euphoria or relief are rooted in brain chemistry. Just like chronic stress floods us with cortisol, short bursts of gender affirmation that feel ‘euphoric’-- are merely releases of serotonin and dopamine. But those highs aren’t sustainable. You can’t live in euphoria.

That’s why drugs like ecstasy, which flood your brain with neurochemicals that make you intensely happy, always give way to harsh crashes in the form of intense, prolonged depressive episodes. That’s just human nature. It is a necessity of our human biology that we’re not meant to feel amazing all the time. There are limits to our biology. Some people may deeply desire to become the opposite sex—but it simply isn’t possible. Even surgeries and hormones, which can alter external appearance, come at great cost. And they may not succeed in making someone “pass” long-term.

Eventually, every transitioner must face the truth: they are still their biological sex. Engaging in social, legal, medical and surgical alterations so as to be recognized as the opposite sex, will not turn you into any version of the opposite sex—trans or otherwise. Nothing will be able to erase that fact. If you base your well-being on the premise that everyone else will affirm you and that you’ll never be misgendered, you will suffer because in a free society, you can’t control the way other people think and speak. If you base your well-being on achieving euphoria through body modification, that euphoria will eventually wear off. And when it does, the consequences may already be permanent.

My advice as a detransitioner to anyone who is currently considering transition, or has embarked upon it and is considering ‘taking the next step’ is this; instead of experiencing doubts and thinking “Does this mean I’m cis/ not trans?” instead ask yourself “Can I predict that what I am doing now will ‘work’ forever? And if not, will I be able to support myself, financially and emotionally, to live with what that means for the rest of my life?”

Did You Enjoy this Essay? Does my work teach you things?

If so, please become a paid subscriber to support my work, so I can continue bringing my insights to you. As a 25 year old independent writer, your $8 a month is very much appreciated.

Maia’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider a paid subscriber.

Do you have a kid navigating gender confusion and trans identification?

If so, I offer parent coaching consultations to help you figure out how to best navigate your specific child’s situation, in a compassionate and practical way. If this is of interest, please DM me.

Maia, your ability to describe these experiences and these processes such that the reader can understand and empathize is remarkable. I grieve for the pain you've borne and marvel at your compassion, your insight, and your eloquence. You're talking about my son as if you know him personally--and about tens or hundreds of thousands of others. More importantly, you're talking about what could happen to myriad others, unless we make a change. Thank you for spreading the word.

Brilliant job explaining, with compassion and clarity.

I’m sending this to two physicians, who I hope will share with their colleagues. Health care providers need to understand the the pitfall of unrealistic expectations and the problems that can be *caused* by transition.

Bravo, Maia, and thank you.