Trans: When Coping Mechanism Becomes Identity

"When an Identity Takes Root"-- Gender Identity Ideation series, part 1

(Note: The play button at the top of this post is NOT a decoration. I have painstakingly audiotaped myself reading my essay, with a special little ad-lib at the end for my listeners. Please click on that play button if you would prefer to hear me reading this essay which I have written. Without further ado— I hope you enjoy the paper. Please comment your thoughts. I genuinely enjoy reading them.)

When a Trans Identity Takes Root:

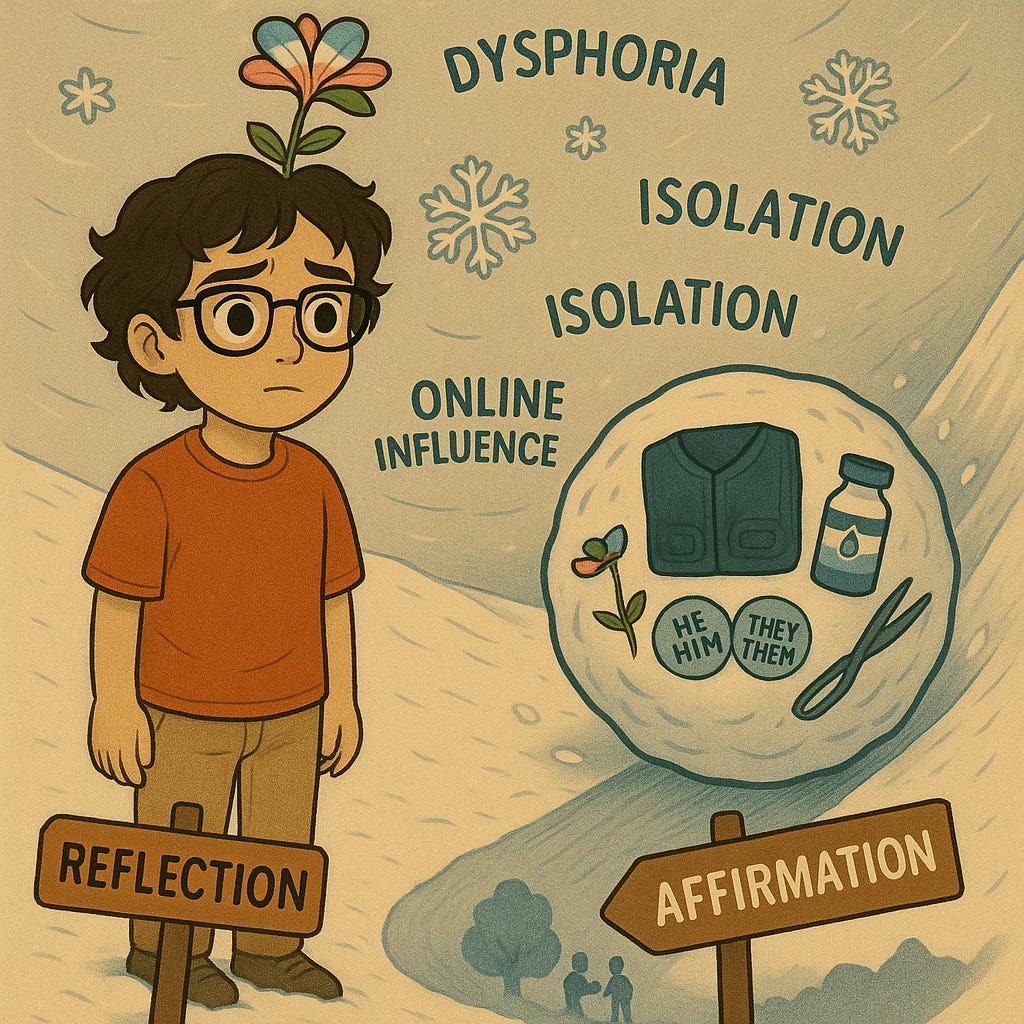

When a teenager adopts a transgender identity, it is often presented as a simple declaration: “This is who I am.” But that declaration is rarely simple. It tends to emerge from a web of distress, disorientation, and unmet emotional or developmental needs. And while the identity may initially feel like a lifeline—a form of clarity or relief—it quickly becomes more than just a label. The longer it persists, the more deeply it entangles itself with the teenager’s personality, social world, and developing sense of self. What may have begun as a coping mechanism for specific discomforts often becomes a central organizing principle of identity—making it exponentially harder to return to a sex-based understanding of the self.

We are, by now, well aware of the risks associated with medical and surgical transition—the panacea it promises, and the devastating outcomes it far too often delivers instead. But what our society remains largely unaware of are the harms of social transition. This is partly because most people get their information from culture warriors, and social transition—unlike hormones or surgeries—has been thoroughly neglected by the broader discourse, despite its seriousness.

Readers of my Substack are already more informed than the average person about the risks and unique harms of social transition, both as a standalone intervention and as the step that almost always necessitates medical and surgical interventions to be sustained. There’s a common tagline used to describe this pattern: “Social transition leads to medical transition.”

Among those who haven’t encountered this idea—or who don’t yet understand how the process tends to unfold—some may affirm their adolescent’s transgender identity, perhaps not as literally true, but by “going along with it”: using the new name and pronouns, purchasing a breast binder for their daughter, or making small concessions under the belief that it’s not a big deal. Only later—sometimes years later—do they realize what a big deal it was, when the child, unsatisfied with social transition alone, begins requesting hormonal and surgical interventions.

Others take a different approach. They may watch their child like a hawk for any sign that a social transition is beginning, and try to intervene at the earliest possible stage—often not from the moment the identity is declared, but anxiously waiting for the moment any visible step toward transition is taken.

Both of these strategies often arise from fear of losing the relationship entirely by taking too definitive a stance; the hope is to minimize conflict, keep the peace, and buy time for the kid to grow up and magically divest themselves from their transgender or non-binary identities. These are well-intentioned moves, but they’re not strategic ones.

I would argue that the most effective strategy is neither the one that permits social transition as a compromise for delayed medical transition, nor the one that scrambles to intercept signs of transition after the identity declaration has already been made—especially when that strategy arises from emotional reactivity or a fear of confrontation. Instead, we need to understand and address what comes before any of this: the phase of ideation. Early intervention, after all, is key.

When most people hear the phrase “social transition causes medical transition,” their analysis stops there—usually because they don’t have a personal stake in the matter. Few pause to ask: What causes social transition? Why does a child begin to identify as transgender in the first place? What motivates them to change their name, their pronouns, their clothing—and ultimately, their bodies?

Because I pride myself on not being like most people—and because I’ve lived this experience for nearly the entirety of the part of my life where I had any awareness of myself as a separate person from my parents—I asked that question. And I decided to try to answer it.

So: What makes someone want to begin a social transition, and then a medical one (or vice versa)? In my opinion, it is the phase of ideation—the internal process of imagining oneself as the opposite sex or as something outside of one’s biological sex—that sets the entire trajectory into motion. There is a complex psychological process which occurs when a teenager adopts a cross-sex identity and either is allowed to pursue it, or isn’t allowed to pursue it but nonetheless persists in the identification. Ideation, at least within my own experience, was by far the most psychologically defining element of my transition– and I suspect it is like this for others as well. The web of complicated internal processes which a young person processes through the sole framework of gender identity is one which, even if individual parents refuse to affirm, our entire culture encourages it to solidify. This phase of ideation is so integral to the transition process, and it is almost entirely neglected in our mainstream conversations about gender identity and transition.

So little is understood about ideation—this initial, often silent period of questioning that precedes any declaration of transgender identity. While we hear a great deal about the stages of transition in the social, legal, physical, medical, and surgical realms, it is the ideation phase that I believe is the most influential. Not only because it is the gray area that exists before any visible steps are taken or any public declarations are made—but also because ideation continues in the background throughout the entire process, quietly propelling the individual from one stage to the next.

In my own search to understand how this happened to me, I realized that many of our fundamental misunderstandings about the psychological nature of gender identity could be clarified—if not entirely dispelled—by collectively asking this one overlooked question: What causes ideation? What unmet need is being filled by the idea of transition?

So, I have chosen to answer this question—starting with my own story.

Those who find themselves in the position of helping a gender-questioning young person, especially their own child, need more than a tagline to guide them. They need context. They need insight. They need an understanding of why the child is drawn to this identity in the first place, not just a plan for how to prevent medical harm.

So let’s talk about ideation.

This essay will be presented in at least two parts. In this first installment, I’ll use a snippet of my own life story to illustrate just one layer of the initial life confusion which, when I was introduced to the transgender sense-making framework, catalyzed the ideation I experienced as a confused 12-year-old. These events were in the works for years before I ever declared a transgender identity to my parents. In the next essay of the series, I’ll discuss how mishandling the ideation phase, even with well-meaning and non-affirming parenting strategies, can increase household tension, damage the parent-child relationship, and ultimately make both social and medical transition far more likely, while also predisposing a young person to other vulnerabilities than their parents may not be able to predict. I’ll also offer some alternatives—approaches I believe are not only more effective but ones which are better able to meet the developmental needs of the child.

Because if we truly want to help children reconcile with their bodies, we should really start before they transition—not after. If you haven’t read my essay titled “How Transition Makes Dysphoria Worse Without You Realizing it,” now would be a good time to do so.

How Transition Makes Dysphoria Worse Without You Realizing It

For those grappling with gender dysphoria, transition is often presented as the only viable path to relief—a linear journey from suffering to self-actualization. The dominant narrative insists that transition, whether social, medical, or surgical, will align the mind with the body, ease psychological distress, and allow a person to live authentically. B…

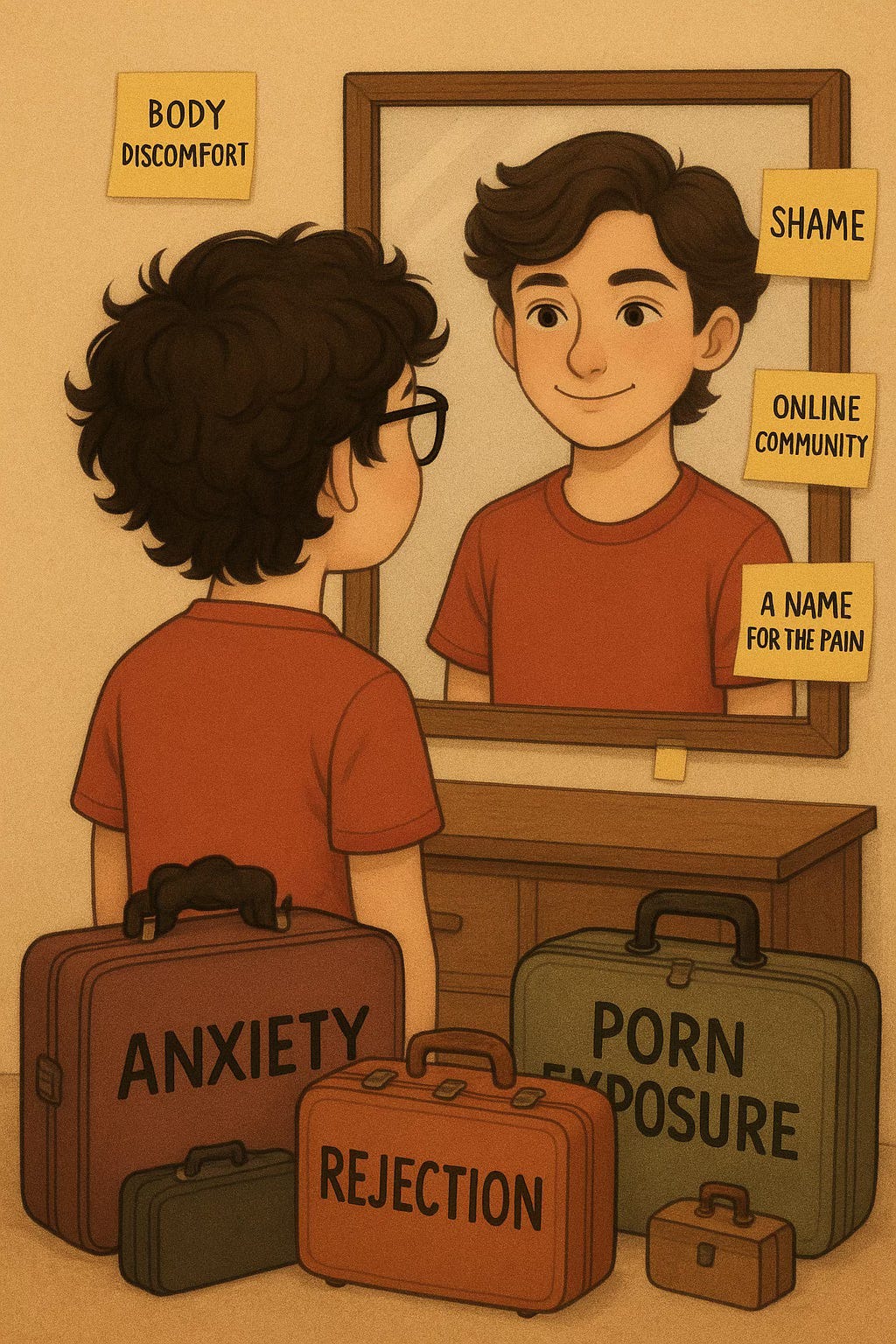

Ideation as The Birth of the Identity, and as Coping that Masquerades As Clarity

For many young people, the transgender identity is not born from a deep, intrinsic knowledge of the self but from normal developmental confusion– and at the beginning of the ideation process, some part of them understands that. Body discomfort, social anxiety, an inability to understand one’s own emotions, trauma, ambivalence or shame about same-sex attraction, fears or confusion surrounding sexuality due to early exposure to pornography and other age-inappropriate materials, or simply a profound sense of not fitting in when coupled with the adolescent need to individuate—any of these can create fertile ground for the idea that one’s “true self” lies on the other side of a gender divide. This identity can feel like both an escape hatch and an answer key: suddenly, there is a name for the pain, a script to follow and a way out of the suffering.

But just naming the distress with the easiest to understand framework doesn’t actually resolve it. Instead, it offers a new framework—one that has over the course of half of my life, gone from being obscure and unknown to the subject of a raging culture war. These days, the trans identity framework is often reinforced as being literally correct by peers, therapists, online communities, and even institutions. The label of “trans” quickly becomes not just a way for a struggling teenager to understand their present confusion, but as a way by which to reflect on negative, confusing aspects of their past, and offering the reassurance of being a sound blueprint for the future.

One major factor underpinning the distress which catalyzed my transgender identification is something I have just begun to unpack now, despite its ever presence throughout my life; sensory processing issues. The next section of my essay will focus on that.

I Didn’t Know How to Use My Own Words to Ask for What I Needed, So I Came Out as Trans

When I was 12 and came out as trans to my parents, they reacted in what I perceived to be an extremely emotionally unpleasant way. As an adult, after consulting many people who are far more literate in emotional nuance than I am, I now understand that this broadly unpleasant emotional reaction was, in fact, panic. But back then, I didn’t know what panic looked like. I thought they were angry at me. That panic—interpreted through my 12-year-old lens as anger—was the moment everything changed. It became the catalyst not just for making an identity claim, but for beginning to construct an entire life plan based on the belief that transition was my only viable future. I told myself I’d figure out how to get the clothes I wanted, how to negotiate for a shorter haircut over time. I didn’t have a male name picked out. I didn’t demand new pronouns—those things hadn’t even occurred to me in 2012. I genuinely believed this was something my parents would help me figure out. They had always been master problem-solvers. But instead, in my highly sensitive, already confused 12-year-old mind, I felt like I had unleashed something catastrophic. I felt like I had caused an emotional earthquake, and that I was to blame.

I didn’t threaten suicide. I didn’t use emotional blackmail. I had heard the messaging about high trans suicide rates for kids who aren’t affirmed, but I didn’t think to tell my parents I was suicidal when I wasn’t, because that would have been a lie. Was I miserable and confused? Absolutely. Was I suicidal? Not until I kept hearing, over and over, that kids like me became suicidal if they weren’t affirmed—then I began to consider it. At that age, and with my delayed understanding of how people use emotion to manipulate others, the concept of emotional blackmail simply would not have occurred to me. I took people’s feelings at face value. I barely understood what constituted “normal” emotional expression, let alone the complicated emotional maneuvers my peers were already using to subtly compete for social standing.

Looking back on it, all I really wanted was just to wear more masculine styles, because I wanted no-fuss clothes. If given the choice, I would have happily worn my previous school’s gender neutral uniform—blue slacks and a soft red or white polo shirt—every single day, because I was used to that. But when I transferred to public school at the age of ten and suddenly had to pick my own clothes, I struggled.

At first, some of the girls’ clothes looked nice on the mannequin, but when I actually put them on, I couldn’t stand how they looked or felt on my body. I would buy them, convinced I could get used to them, only to find myself miserable every single day. I was constantly pulling at the fabric of my shirts, trying to keep it from touching my skin, trying to stretch it out and becoming endlessly frustrated when the fabrics did not comply. If I hadn’t gotten much sleep the night before, the textures of these clothes made me irrationally angry. I refused to wear jeans—not because they came from the girls’ section per se—but because I couldn’t stand the texture of denim. My mom tried to buy me high-quality, soft jeans, but they still had no pockets and the waistband pressed uncomfortably against my stomach, even in the right size.

I knew what slacks were. I was used to slacks. I wanted slacks. But I had hit a growth spurt, and none of my old ones fit. What I wanted was simple: pants with pockets, shirts that didn’t cling to my body, no tags digging into my back, no sequins or iron-on rubbery decals scraping against my skin. I wanted relatively plain clothes I could pull randomly from a drawer without having to think about how they matched, because clothing was not something I wanted to give my mental energy to. I wanted my old uniform back. I thought about this, but I didn’t think to actually say it. There was no predictable script, no easily memorized phrase I’d heard someone else say that I could repeat to express this exact feeling.

At that age, I would have much rather spent an extra fifteen minutes in the morning reading about autism, a rare brain tumor, or re-reading The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother for the 27th time– than I would on trying to decode emotions that I didn’t even know were emotions, or trying to dress myself or even comb my hair. I didn’t know how to explain why I hated girls’ clothing so much—I just knew that it made me feel like I was crawling out of my skin. Each day brought new clothing textures I couldn’t predict or prepare for. In my uniform, I knew how the clothes would feel on my body every single day, and that was comfortable for me. Though I was quite a spontaneous child as I am now a spontaneous adult, there were a few things that I was a stickler about, and wanting to wear the same thing every single day was one of them. But when you go to a school where everyone wears their own clothes, that’s something the other kids would notice and make fun of me for– which I would not have intuited and which my parents very much knew. So they reminded me to change if they saw me in the same outfit twice in a row.

Eventually, I realized that saying I was a boy might be the only way to get what I wanted—because that’s how this type of request was modeled in the documentaries I watched about “trans kids.” I also simply couldn’t find anything in the girls’ section that met my strict sensory requirements, and maybe I could have been more persistent in this pursuit, but I couldn’t stand the flickering fluorescent lights in clothing stores. They gave me headaches and made me so irritated that I didn’t want anything to do with extending my time in a mall. I would come into a shopping experience excited about finally replicating the predictable sensory experience I once had, and emerge dissatisfied with the clothes I returned with every single time. I convinced myself I could get used to this new public school hell of wearing my own clothes, if I just kept amassing more clothes I thought were shiny, colorful and pretty on the mannequin, but couldn’t stand the look or feeling of them on my body… probably because this type of self-imposed “exposure therapy” is something I read in a parenting book.

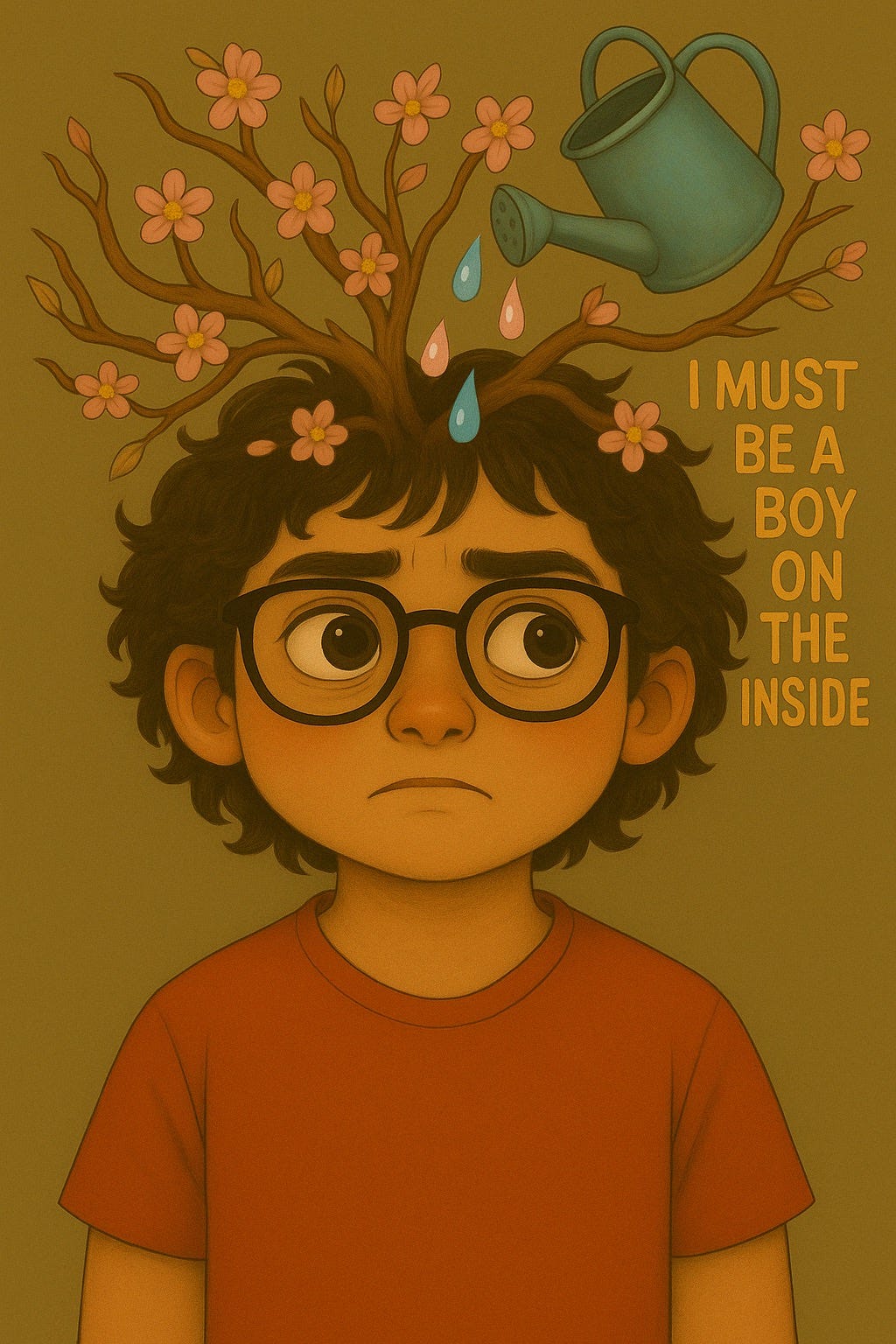

I didn’t understand why these “girly” clothes made me feel like I wanted to rip off my own skin. As a 12-year-old, I hadn’t yet gotten far enough in my self-directed autism research to understand what a sensory processing disorder even was—I was still more interested in the possibility of locating autism in the brain by studying differences in gray and white matter. I had a strong impulse that wearing more formless boys’ clothes would make me tolerate embodiment better, but I didn’t know why. What I did know was that it was statistically unusual for a 12-year-old girl to have zero interest in wearing low-cut shirts, a full face of makeup, or trendy clothes covered in frills and glitter. I looked at the girls my age and thought, “There’s no way I could do that.” And because I couldn’t model myself after my same-sex peers—because I didn’t like what they liked—I concluded that I couldn’t make the requests I needed to make for different clothes or hairstyles unless I had a reason. The reason became: I must be a boy.

So when I adopted the transgender identity and “action framework” as the only legitimate explanation for my distress, and when I came out to my parents as transgender and asked for the short haircut and the new clothes in styles I wanted to wear, they initially squashed it all. Immediately. No discussion. No compromise. Their strict stance on self-expression became a battle which I had attributed to my sex as a problem which prevented me from being allowed to explore the types of styles I enjoyed.

In retrospect, the request I made as a seventh grader—to be seen as a fundamentally different person than the one my parents had raised—was enormous. But what I actually wanted wasn’t complicated: I wanted short hair, because as a kid I had short hair. I didn’t have to brush it or style it. I didn’t have to feel it on my neck. Tying it back hurt my head. Leaving it down felt like a sweaty scarf on my shoulders. The sensation of hair on my neck made me want to rip it out. When I saw parents taking their five-year-old “trans sons” to get their first boys’ haircuts, I thought: That would make me feel better.

I believed I knew why—that it was because I had a male soul which compelled me to dislike uncomfortable clothing styles and long hair, that I had finally located the source of my discontent. But the truth was that I had simply adopted a spiritual explanation to rationalize sensations and emotional signals that I could not otherwise make sense of. Rather than a transcendent, ineffable truth about myself, what I was experiencing was a sensory processing issue. But I didn’t know that. I didn’t know how to explain it. All I knew was that girls my age didn’t have short hair. Only boys did. So if I wanted to shave the sides of my head like my brother, that must mean I was supposed to be a boy. I didn’t have any alternate explanation.

What started as an inability to understand or express my sensory needs, my emotional confusion, and the chaos of puberty became something much more rigid. I didn’t know how to talk to kids my age about what I was feeling—honestly, I didn’t even know that was something people did. Talking about emotions felt like a trap. Explaining my feelings made me feel incompetent. But I could memorize an encyclopedia’s worth of facts about pituitary tumors, China’s tallest woman, and the brain condition that killed her—and that competence felt much safer. I didn’t know emotions were sensations in the body. I thought they were just exaggerated smiley and frowny faces, which I had never connected to any inner bodily state. And I hated feeling incompetent. So I never even tried.

I assumed I was the only one who felt this disorienting blend of discomfort and confusion. So when I found a framework that seemed to explain it all—the documentaries, the stories, the medicalized narratives—I latched on. And I held on tight.

The shift from wearing a uniform to dressing myself happened the same year I hit puberty. Within that one year, I lost the sensory stability of a predictable outfit and gained the sensory onslaught of early breast development, bras, and the constant awareness of a changing body. These two events—uniform loss and puberty—were, in hindsight, both major disruptions. But because the trans identity didn’t appear until two years later, no one connected the dots. The other struggles I had during that time were handled individually, for what they were. But the gender identity crisis, even for my skeptical and highly involved parents, was treated as something entirely different—something so big, so dangerous, that it needed to be shut down immediately instead of examined carefully.

When my parents rejected my conclusion—that I was meant to be a boy—they didn’t stop to ask what had brought me to that belief in the first place. They never thought to ask whether something besides “too much screen time” or “we shouldn’t have gotten her an iPad” might have played a role. So they took away the iPad. But it didn’t fix anything. Because the iPad wasn’t the root of the problem.

The root of the problem was that I had fundamental misunderstandings about the nature of reality itself—misunderstandings shaped by longstanding social, emotional, and sensory processing deficits, compounded by my young age and by the fact that I was a girl. And because I was a girl, those deficits had gone unrecognized and unaddressed despite their severity for quite a while—because for a long time, no one really understood how autism and ADHD manifest differently in girls. And because no one understood, those traits snowballed. The deficits that I used my transgender identity to mask went totally unaddressed in my parents’ incredible attempts to get me to reconcile with my sex, these now got eclipsed even more in their attempt to squash the identity rather than to guide me through the process of understanding why I felt this way. And what followed was more than a decade of my life that no one—least of all me—could have predicted.

It is critically important that parents understand that there may be aspects of their child’s experiences and struggles which they are totally in the dark about. Maybe they have impulses they’ve dismissed because they think their child’s texture pickiness has nothing to do with why they think they’re in the wrong body. It is prudent for parents to not discount these impulses when they are coming up with a strategy. I write more about the way these sensory processing issues may be rationalized by some young people who embark upon the transition pathway in my essay titled “Why Do So Many Autistic Girls Bind Their Breasts?”

Why Do So Many Autistic Girls Bind Their Breasts?

Less than a week after graduating from high school, I celebrated my 18th birthday at an indoor trampoline park with a few of my closest friends. We spent the afternoon climbing ninja courses, doing front flips into foam pits, and throwing foam balls at one another- jumping …

The Importance of Addressing Ideation Before it Snowballs into Social or Medical Transition

There are many misconceptions about the nature of how gender transition unfolds as a process within young people who are still in the phase of individuating from their parents. I believe it is critical for parents and caregivers of gender-questioning kids to address the transgender identification as early as possible. It is dangerous to assume that every child will “just grow out of it” as long as they aren’t affirmed and are allowed to go through puberty. While that assumption may hold true for the children who grew up in a culture that didn’t affirm cross-sex identities at every turn, and who had prepubertal-onset gender dysphoria, it is naive and risky to apply the same lackadaisical “watchful waiting” approach to the cohort of teenagers whose gender questioning is highly socially mediated and begins around or after the onset of adolescence.

Why? Because adolescence is precisely the developmental window in which young people form identity. They are constructing their self-perception—trying to understand who they are and how they fit into the world. Trans identification, as we now know, latches onto this process with impeccable ease. If this stage of ideation isn’t properly addressed, the result is not neutral. Suppressing all identity exploration and self-expression is harmful to adolescents, yes—but so is allowing a new, rigid, and socially reinforced identity to take over and usurp the one rooted in biological reality. Once that new cross-sex identity becomes central to the young person’s sense of self, it is extremely difficult to dislodge—even after it has long outlived the psychological and developmental purpose it originally served.

The Reason to Address Ideation Now Rather than Hoping Non-Affirmation Alone Will Resolve Gender Questioning

From the moment a child, teenager, or even a developmentally delayed young adult adopts a transgender identity, the clock starts ticking. If your child is 12, as I was, you may think—like my parents did—that you have plenty of time before they turn 18. You may assume it’s just a phase, one that will resolve on its own. I’m here to tell you: it would be a miracle if that were the case. And I don’t give advice based on miracles. I give advice based on the brutally honest reality of the situation, because telling you to hope and plan for a miracle is irresponsible– because you and your kid deserve better than to be lied to about the intricacies of a trajectory with such high stakes.

The truth is, the trans zeitgeist is everywhere. It lurks around the corner of every school hallway, library, the internet, TV shows, social media– the idea that bodily discomfort around adolescence is a sign that one is born in the “wrong” body has thoroughly pervaded our every institution. Every developmental and social incentive in the current culture—regardless of the specific motivations your child may have for identifying as transgender or non-binary—actively encourages them to double down. Nothing, and no one, but you stands between your distressed, desperate child and permanent, life-altering decisions that they are far too young to fully comprehend—especially if they reach legal adulthood while still functioning cognitively and emotionally as an impulsive adolescent.

I say this from the perspective of a 25 year old who made it out of the transition pathway after spending half of my life within the ideation and social transition stages of this pathway: the last thing you want to do is wait until right before your child turns 18 to try to “sort it out.” I know—because that’s what happened to me. If your child has spent their entire adolescence steeped in this identity, the transgender self-concept may be the only version of a semi-autonomous self they even recognize. As your child grows, their trans identity grows in lockstep—shaping their worldview, their social relationships, and their personal development in real time. And in just a few years—sooner than you think—your child may no longer remember who they were before the identity took hold. They will have spent their most formative years dreaming of, or actively trying to become, an entirely different person. Perhaps you are already there.

At that point, how can anyone reasonably expect a young person to return to an identity based in biological reality, when the last time they embodied that version of themselves, they were likely still a preteen—or even younger—with no semi-mature or stable sense of self?

Usually, a long-term trans identity even in a non-affirming household can persist because the original confusion or distress that led the child to latch onto this identity—this particular coping framework—has never been adequately addressed. The trans identity can become a vehicle for managing distress that might otherwise have been resolved or mitigated with proper support. I’ll explain more in the following essays that this situation doesn’t necessarily arise because of parental negligence. This dynamic can unfold in families with highly engaged, loving parents who still, despite their best efforts, get caught up in the weeds. They fixate on the aesthetic trappings of the identity, they focus on listening to their kids for the sole purposes of debating the non-factual nature of their identity claims, in the hope that they can avoid the consequences of affirming the identity. And in this chaotic process, parents can easily miss the most basic clues about why their child came to this conclusion in the first place—and how to help them out of it.

Conclusion: Looking Ahead, With a Note on the Origins of My Perspective

Normally, my essays have much more substantive conclusions because they cover multiple ideas. This essay was supposed to be like my others, until I wrote up the first draft and it was 25 single-spaced pages. Since I’ve had to split it up in awkward ways to address these ideas with the care with which they ought to be addressed, this conclusion will be less about the ideas themselves and more as a sort of breathing exercise for the inner strategists among us.

Though there is no one-size-fits-all solution—no magic bullet, no single sentence you can say that will instantly change your child’s course when it conflicts with what they’ve already decided—there are strategic ways to induce more critical thinking in a young person. There are methods you can adopt that help you better understand your child’s mindset, gather the missing pieces of this deeply personal puzzle, and make more informed choices about what kind of support, environment, and boundaries will actually be effective in helping them feel more at home in themselves. Some of these strategies involve asking thoughtful questions in a calm tone, while others involve bonding over anything but gender and using financial support as leverage. I personally think that the strategy I would have benefitted from which I haven’t heard articulated yet, is the strategy of becoming a detective and asking questions which help parents to gather insight into their child’s mindset as a gauge. This is a strategy I will discuss either in part two or three, depending on where it makes most sense to do so.

Just because the missing puzzle piece in my case turned out to be sensory processing issues and certain undiagnosed autistic traits doesn’t mean those are the same drivers for your child. They might share some parts of my story. Or none at all. Your child may be just like me in some ways—or completely different. Each young person is a complex individual, and every family dynamic is unique, shaped by the personalities, temperaments, and communication styles of everyone involved.

You may know your child better than anyone else in the world—better, in some ways, than they know themselves. But especially if your child is highly cerebral or emotionally reserved (or as in my case, pretty emotionally illiterate), there are likely parts of their internal world you haven’t had access to yet. And that’s not a failure on your part. That’s just the reality of the situation.

What I offer is not a clinical framework or therapeutic toolkit. I’m not a psychologist. I’m not a therapist. If I had to deal with helping people decode their own emotions all day, I’d find myself trying to catapult off of a bridge (metaphorically speaking– don’t worry guys). What I am, is a 25-year-old who got pulled into transgenderism so young that I honestly don’t entirely remember a version of myself that wasn’t obsessed with it. I have spent over a decade of my two and a half decades on Earth immersed in this phenomenon—not because I studied it in school, but because I lived it. I got in early, stayed too long, and found my way out. And in the process, I developed the ability to notice missing pieces that therapists and parents often overlook—not because I have special insight into emotions, but precisely because I don’t. I don’t process emotions intuitively, either my own or other people’s. Every conclusion I’ve arrived at about this topic has come from a place of logical deduction, an insane amount of research, and a methodical piecing-together of what didn’t make sense to me about my own experience, and about what eventually did. I am not a therapist, but I am a strategist.

That’s the lens I can offer you: a bird’s-eye view of the transgender phenomenon broadly, and within young people and their families—not from a place of ideology or expertise, but from personal experience, reflection, and reasoning. If you’re struggling with how to help your child through this gender identity crisis and you want someone who can help you think through your family’s situation without judgment or political spin, and to come up with a better strategy, I’d be honored to help. I apply the same analytical style of thinking to others’ situations that I’ve used to deconstruct and to better understand my own. If that sounds like something you’d benefit from, you’re welcome to reach out. Please DM me to book a parent coaching session.

And finally, stay tuned for Part Two, which will be published shortly. If I can’t fit everything into that installment—just like what happened with my Jazz Jennings series—there will be a Part Three. These follow-ups will be available for paid subscribers. As always, your support helps me continue producing in-depth, high-quality content on this subject—and bringing these conversations to the people who need them most. Your comments are much appreciated.

Part Two is OUT now:

Trans: When Adolescent Survival Strategy Becomes Family Breakdown

Note: The "play” button at the top is not a decoration. It is an audio-taped version of myself reading this essay. Also note, there are videos in the first section of this essay, so if you are a listener, keep this in mind.

Did You Enjoy this Essay? Does my work teach you things?

If so, please become a paid subscriber to support my work, so I can continue bringing my insights to you. As a 25 year old independent writer, your $8 a month is very much appreciated.

Maia’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber by clicking on any of the buttons in the post.

Do you have a kid navigating gender confusion and trans identification?

If so, I offer parent coaching sessions to help you figure out how to best navigate your specific child’s situation, in a compassionate and practical way. If this is of interest, please DM me.

This is awesome! :)

I am 100% Team Wear The Same Thing Every Day When You Know What Feels Best. I buy multiples of everything I love, in every size I might want or need to wear. Yay for simplicity!

This was an excellent essay and I look forward to reading the other parts to it.

You mentioned several times about how you would research autism and the brain as a child. Did your research ever get into the principles of applied behavior analysis and how to determine the function of a behavior? It seems to apply perfectly to what you're describing as detective work and understanding why the child has adopted this particular coping strategy. There are four traditional functions of behavior: escape/avoidance, sensory, attention seeking, and access to tangibles. The idea is that when a child has a behavior you're trying to understand an address, you have to understand the function of that behavior. So if you have a child who keeps hitting the child sitting next to him during circle time, you have to figure out what the function of that behavior is or else the adults responses to the child's behavior may either do nothing to address it or even reinforce it and make it more likely to reoccur. For example, if the child is hitting because he doesn't like circle time and wants to leave (avoid) it, putting him in time out on the other side of the room is actually reinforcing the behavior and making it more likely to occur. you are describing classic sensory functions of behavior. Some experts have added some nontraditional functions of behavior to the traditional four such as control/autonomy seeking, relational/identity seeking, play/exploration, and justice/revenge seeking. Some of these non traditional ones could be especially applicable to teenagers with ROGD patterns.

Just like you said in the conclusion of your essay, there is no one answer to how to approach or talk about this with a young person because you have to figure out the function of the behavior, in this case the function of the trans identity. Unfortunately, a lot of current autism activism has demonized the principles behind ABA so much to the point of calling them abusive that this very basic and important understanding of psychology and how we can help young people has been the baby thrown out with the bathwater. Behaviorism and more behavioral approaches to psychology have fallen out of favor in many areas and I think we have lost a lot because of that. Without this framework of understanding the function of the behavior I feel like it becomes even easier for this issue to get lost in cultural and philosophical wars politics.